“Books in the West”

from

Morely Roberts’s A Tramp’s Notebook

Since taking to writing as a profession I have lost most of the interest I had in literature as literature pure and simple. That interest gradually faded and “Art for Art’s sake,” in the sense the simple in studios are wont to dilate upon, touches me no more, or very, very rarely. The books I love now are those which teach me something actual about the living world; and it troubles me not at all if any of them betray no sense of beauty and lack immortal words. Their artistry is nothing, what they say is everything. So on the shelf to which I mostly resort is a book on the Himalayas; a Lloyd’s Shipping Register; a little work on seamanship that every would-be second mate knows; Brown’s Nautical Almanacs; a Channel Pilot; a Continental Bradshaw; many Baedekers; a Directory to the Indian Ocean and the China Seas; a big folding map of the United States; some books dealing with strategy, and some touching on medical knowledge, but principally pathology, and especially the pathology of the mind.

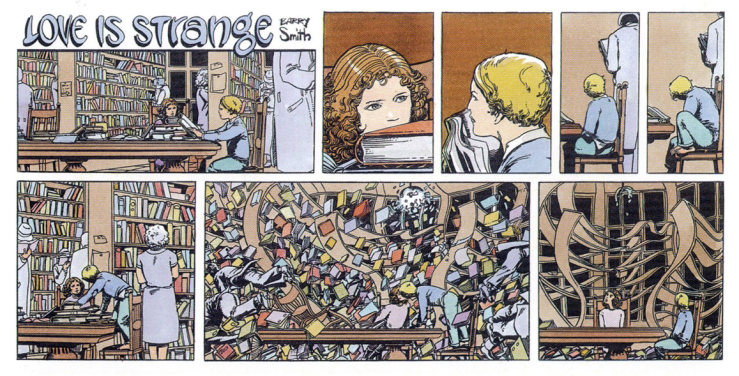

Yet in spite of this utilitarian bent of my thoughts there are very many books I know and love and sometimes look into because of their associations. As I cannot understand (through some mental kink which my friends are wont to jeer at) how anyone can return again and again to a book for its own sake, I do not read what I know. As soon would I go back when it is my purpose to go forward. A book should serve its turn, do its work, and become a memory. To love books for their own sake is to be crystallised before old age comes on. Only the old are entitled to love the past. The work of the young lies in the present and the future. Continue reading ““Books in the West” — Morely Roberts” →