An intriguing and confounding section of Chapter 1 of Part II of William Gaddis’s 1955 novel The Recognitions focuses heavily on Esme, the poet who models for Wyatt Gwyon as he paints his forgeries. The episode eventually reveals Esme as one of the heroes of The Recognitions. It begins with Esme cloistering herself, pinning a sign to her door that reads: “Do Not Disturb Me I Am Working Esme.” She begins her “work” in a manic blur, “delighted to be alone.” As her energy shifts, she sews for a bit, before finally switching to attend to her small library:

But before that sewing was done she was up, rearranging her books with no concern but for size. There was, really, little else their small ranks held in common (except color of the bindings, and so they had been arranged, and so too the reason often enough she’d bought them). Their compass was as casual as books left behind in a rooming house; and this book of stories by Stevenson, with no idea where she’d got it, she hadn’t looked into it for years, now could not put it down, and to her now it was the only book she owned.

Esme’s bookshelving is purely aesthetic, and the aesthetic seems arbitrary (and likely temporary). In this little scene she moves from arrangement by color to arrangement by size. Her aesthetic arrangement leads her back to a collection of Robert Louis Stevenson stories (likely The Merry Men, and Other Tales), her current (arbitrary, temporary) aesthetic obsession. The “Esme working” section of II.1 of The Recognitions actually begins with an entire paragraph a Stevenson story, presumably read aloud by Esme. This long quote goes unattributed, but Steven Moore identifies it in his annotations for The Recognitions as part of the Gothic short story “Olalla.”

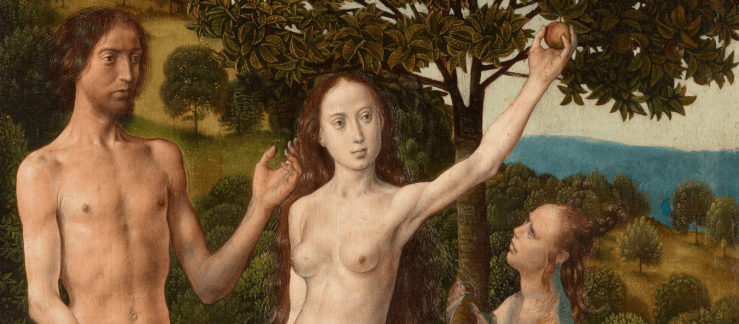

The passage from “Olalla” quoted in The Recognitions begins with the phrase “What is mine, then, and what am I?” Olalla poses these questions to the narrator of Stevenson’s tale, a nameless Scottish soldier who recuperates from wounds in a Spanish hospital and then in the home of a fallen noble family (Gaddis cribs from this plot in the first chapter of The Recognitions, where Wyatt’s father, the Reverend Gwyon, recovers in a Spanish monastery).

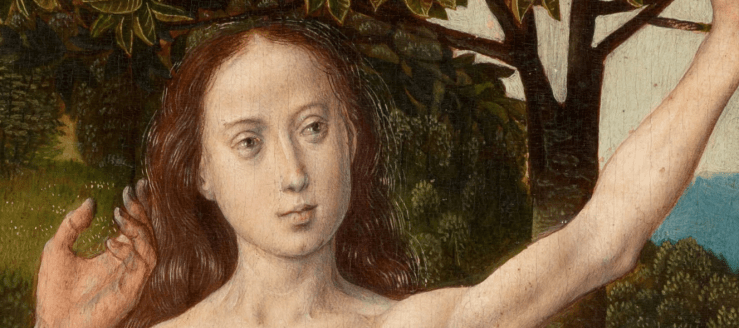

Olalla’s questions are quite literal. She recognizes herself in the paintings of her ancestors, which line the walls of her family’s house, and claims a part of herself in those paintings in a haunting phrase: “Others, ages dead, have wooed other men with my eyes.” Olalla recognizes something in herself that antecedes her ancestors, some essential element that surpasses death and transcends time. She describes herself as “a transitory eddy” in a stream of time (lines not included in Gaddis’s graft from the story): not the original, but the wave that carries the impulse of origination. Her words challenge the notion of a stable, self-present self.

Olalla’s questions — “What is mine, then, and what am I?” — are essentially Esme’s questions. Esme fragments as the novel progresses, and Gaddis rhetorically highlights her looming madness by employing a daunting elliptical prose style in the sections that wander into her consciousness. Consider here, where we learn about Esme the reader:

Even so she had never read for the reasons that most people give themselves for reading. Facts mattered little, ideas propounded, exploited, shattered, even less, and narrative nothing.

This sentence is fairly straightforward—we see how Esme’s reading might differ from the way most of us read. But let’s see where we go next—what does Esme read for?

Only occasional groupings of words held her,

Esme reads discontinuously, perhaps arbitrarily, aesthetically—but let’s let that sentence unwind:

Only occasional groupings of words held her, and she entered to inhabit them a little while, until they became submerged, finding sanctuary in that part of herself which she looked upon distal and afraid, a residence as separate and alien, real or unreal, as those which shocked her with such deep remorse when the features of others betrayed them. An infinite regret, simply that she had seen, might rise in her then, having seen too much unseen; and it brought her eyes down quick.

I’ll admit I find the lines baffling. Esme inhabits the words, which then, strangely, become submerged within her, or a part of her that she has disassociated from her self-present self. The paragraph ends with a shock of recognition. Is this Esme gazing into the abyss? In any case, we see here Gaddis’s rhetorical skill at conjuring complex instability in his subject.

Let’s continue by moving from Esme the aesthetic reader to Esme the aesthetic writer:

The sole way, it seemed to her often enough when she was working at writing a poem, to use words with meaning, would be to choose words for themselves, and invest them with her own meaning: not her own, perhaps, but meaning which was implicit in their shape, too frequently nothing to do with dictionary definition.

And yet it would be too simple to suggest that Esme’s poetry is utterly meaningless, pure sound and shape without content. Rather, her writing is a writing against: A writing against the cheapness of language in a masscult zeitgeist, against newspapers and memos and comic books and flyers and stock ticker tape and museum guides and informational pamphlets and millions and millions of copies of How to Win Friends and Influence People. The paragraph continues, highlighting Gaddis’s fascination with entropy:

The words which the tradition of her art offered her were by now in chaos, coerced through the contexts of a million inanities, the printed page everywhere opiate, row upon row of compelling idiocies disposed to induce stupor, coma, necrotic convulsion; and when they reached her hands they were brittle, straining and cracking, sometimes they broke under the burden which her tense will imposed, and she found herself clutching their fragments, attempting again with this shabby equipment her raid on the inarticulate.

Esme is one of Gaddis’s heroes. Like Jack Gibbs in J R or McCandless in Carpenter’s Gothic or the narrator of Agapē Agape, she forces her will against an entropic dissolving world, and she does so to make art. And in her art she makes her self, or a version of her self, a self apart from the self-present self that might have to haggle and bustle in the tumult of the masscult midcentury metropolis. Esme strives for transcendence from language through language toward a place of pure recognition:

It was through this imposed accumulation of chaos that she struggled to move now: beyond it lay simplicity, unmeasurable, residence of perfection, where nothing was created, where originality did not exist: because it was origin; where once she was there work and thought in causal and stumbling sequence did not exist, but only transcription: where the poem she knew but could not write existed, ready-formed, awaiting recovery in that moment when the writing down of it was impossible: because she was the poem.