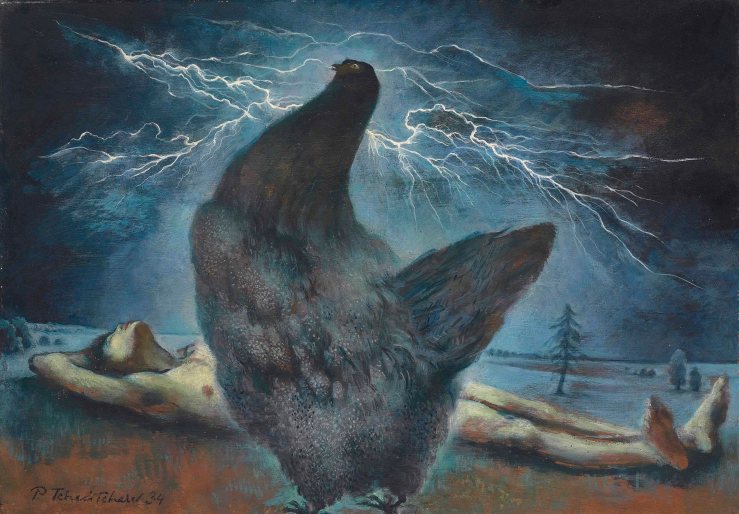

“The Flight of Pigeons from the Palace”

by

Donald Barthelme

In the abandoned palazzo, weeds and old blankets filled the rooms. The palazzo was in bad shape. We cleaned the abandoned palazzo for ten years. We scoured the stones. The splendid architecture was furbished and painted. The doors and windows were dealt with. Then we were ready for the show.

The noble and empty spaces were perfect for our purposes. The first act we hired was the amazing Numbered Man. He was numbered from one to thirty-five, and every part moved. And he was genial and polite, despite the stresses to which his difficult métier subjected him. He never failed to say “Hello” and “Goodbye” and “Why not?” We were happy to have him in the show.

Then, the Sulking Lady was obtained. She showed us her back. That was the way she felt. She had always felt that way, she said. She had felt that way since she was four years old.

We obtained other attractions—a Singing Sword and a Stone Eater. Tickets and programs were prepared. Buckets of water were placed about, in case of fire. Silver strings tethered the loud-roaring strong-stinking animals.

The lineup for opening night included:

A startlingly handsome man

A Grand Cham

A tulip craze

The Prime Rate

Edgar Allan Poe

A colored light

We asked ourselves: How can we improve the show?

We auditioned an explosion.

There were a lot of situations where men were being evil to women—dominating them and eating their food. We put those situations in the show.

In the summer of the show, grave robbers appeared in the show. Famous graves were robbed, before your eyes. Winding-sheets were unwound and things best forgotten were remembered. Sad themes were played by the band, bereft of its mind by the death of its tradition. In the soft evening of the show, a troupe of agoutis performed tax evasion atop tall, swaying yellow poles. Before your eyes.

The trapeze artist with whom I had an understanding . . . The moment when she failed to catch me . . .

Did she really try? I can’t recall her ever failing to catch anyone she was really fond of. Her great muscles are too deft for that. Her great muscles at which we gaze through heavy-lidded eyes . . .

We recruited fools for the show. We had spots for a number of fools (and in the big all-fool number that occurs immediately after the second act, some specialties). But fools are hard to find. Usually they don’t like to admit it. We settled for gowks, gulls, mooncalfs. A few babies, boobies, sillies, simps. A barmie was engaged, along with certain dumdums and beefheads. A noodle. When you see them all wandering around, under the colored lights, gibbering and performing miracles, you are surprised.

I put my father in the show, with his cold eyes. His segment was called My Father Concerned about His Liver.

Performances flew thick and fast.

We performed The Sale of the Public Library.

We performed Space Monkeys Approve Appropriations.

We did Theological Novelties and we did Cereal Music (with its raisins of beauty) and we did not neglect Piles of Discarded Women Rising from the Sea.

There was faint applause. The audience huddled together. The people counted their sins.

Scenes of domestic life were put in the show.

We used The Flight of Pigeons from the Palace.

It is difficult to keep the public interested.

The public demands new wonders piled on new wonders.

Often we don’t know where our next marvel is coming from.

The supply of strange ideas is not endless.

The development of new wonders is not like the production of canned goods. Some things appear to be wonders in the beginning, but when you become familiar with them, are not wonderful at all. Sometimes a seventy-five-foot highly paid cacodemon will raise only the tiniest frisson. Some of us have even thought of folding the show—closing it down. That thought has been gliding through the hallways and rehearsal rooms of the show.

The new volcano we have just placed under contract seems very promising . . .