I don’t want to write what I’m writing, but if I don’t write it I don’t think I will be able to write anything here again. I am not going to work on the thing that I am writing right now, I’m just going to write it and let it be messy and incomplete, riddled with absences, mistakes, oversights, smaller and larger failures, possible and probable grammatical and mechanical errors — but no erasures.

On Monday, this Monday, two days ago, my closest friend, my best friend of over three decades, died unexpectedly in his sleep. He went to sleep and did not wake up. He was there and then he wasn’t, or his consciousness wasn’t there, or isn’t here, or isn’t here in a form I can communicate with, that I know of. I feel as if something unnameable has been ripped out of my world. (He has a name, but the thing ripped out of the world is more than the name, more than the friendship, more than the years.) I have experienced grief before, for both friends and family, social grief and cultural grief and political grief and even parasocial grief. Nothing has ever hurt this intensely, and when the pain disappears it is replaced with hollow anxiety and muted dread.

I first met my friend when my family returned to the United States in 1991. It was during the final semester of the sixth grade. The city we moved to, where my parents had more or less grown up, was conducting a short, miserable experiment which was to put all of the city’s sixth graders into two schools. So, instead of having a junior high or middle school with its separate grades and hierarchies of time, tradition, seniority, whatever, I landed in an asylum crowded with hormonal mutants trying to establish dominance over each other in endless games of petty cruelty. I don’t remember my friend, who was not yet my friend of thirty years, being especially kind to me in any way that I understood as kindness. I do know that he talked to me like I was an actual person and not just a freak who was maybe not actually American. He let me borrow his Aerosmith tapes and copy them on my dad’s tape player. He had no interest in my R.E.M. CD. (I don’t think he had a CD player). Through the end of the sixth grade year we collaborated well together, working diligently in tandem to erode our citizenship grades from A’s to D’s.

We attended different middle schools (I think middle school was a new term, a transition from junior high). The next time I saw him was in ninth grade orientation. The moment of recognition remains one of the most wonderful feelings I’ve ever had: Here was my old friend; maybe he could be my new friend. By the end of ninth grade we were on our third rock band. We had finally found a real drummer. Actually he wasn’t a real drummer, but he was very good at playing the drums, a natural. He played on borrowed sets and we practiced on pieces we slowly put together through different forms of theft. This person, this drummer who wasn’t actually a drummer, he’s dead too now. But back to my friend.

My friend–we played music together forever. Bands in high school, college, after college. House parties, punk shows at the Elk’s Club or whatever the fuck it was, churches, all ages clubs, shitty night clubs, shitty rock clubs. We opened for the Moe Tucker Band and stole all their oranges and beers and drank them on the roof of the club (I never saw the Velvets legend perform; later she joined the Tea Party, I think). We opened for Limp Bizkit when they were still Limp Biscuit. Our drummer’s alcoholic mother was there with some guy who wasn’t his dad. She had no idea her son was there. We opened and played with dozens and dozens of local and touring bands that were so, so fucking good, and sometimes we were so fucking good too. We put out an album. We made endless four track recordings, as a band but also as a duo, also just swapping tapes. (We also swapped notebooks for two years — I want to say most of tenth and eleventh grade — where we worked on a “novel.” The “novel” was awful but it was so so so much fun to write. We would trade off chapters with no plotting in mind, changing the genre or direction of the tale, mostly just practicing, I guess. I guess I just liked reading what he wrote and maybe he liked reading what I wrote.) In college we played fewer shows out but recorded music more seriously. We made a Christmas album and gave CDs to our friends and family. I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to listen to it again, although I’ve had my friend’s vocal on “Silver Bells” running through my head since Monday morning, the morning I was sitting here on the black leather couch I pretend is an office where I am sitting here right now on Wednesday morning, forty-eight hours after his wife called me with the awful awful news that my friend had died in his sleep.

I am ranting of course, and I would apologize, but this isn’t for any reader and this isn’t an elegy for my friend, this is for me. Maybe what I am trying to emphasize is that our friendship, our love for each other, was deeply wrapped up in creation, in art, in a lifelong discussion of music, art, film, literature. He encouraged me to start a blog. He told me he thought I’d be good at it. He was, I’m pretty sure, the only reader for this blog for the first few months.

He always gave me his honest opinion. When I was doing something that he thought was not good, he told me. If he thought I could do better, he told me. People use the term “partner in crime” as a cute way to describe their closest friend; we were actual partners in actual crimes. Most of the crimes were petty and none of them were violent. They were all stupid, and we learned from them, I think.

We traveled together, we were in each other’s weddings. We walked into adulthood, or whatever it is we are dealing with here, in different ways. I married at a younger age and had kids much younger than he did, which made him erroneously believe that I had some expertise in these matters. We were texting about his wife and his kids on the Sunday that he did not wake up from. We were texting about the finale of The Righteous Gemstones, which we were both looking forward to. (My wife was too tired to watch it that night–did my friend get to see the end? Is this the stupidest thought I’ve had over the past few days? Maybe because it’s one of the last things we were texting about. And the last thing he texted in our last conversation: how excited he was about the forthcoming Stereolab record. We were reminiscing about cruising around in his old jeep, the “Red Death,” as we called it, blasting Emperor Tomato Ketchup all summer, the summer before senior year. I am not a God I wish I could go do that one more time person, but now maybe I am, maybe like, God I wish I could cruise around just one more time like that with you person.) So well anyway, we were texted about Big things but also Small things, mundane stuff, day-to-day stuff. We texted every day, throughout the day. He only lived forty minutes from me, but we didn’t get to see each other as often as we’d like to (work, kids, life…). So we were in a state of constant written communication, passing ideas and jokes and observations back and forth, then bursting into the Big stuff, the new challenges of Growing Up.

I don’t think I ever really felt scared of any new frontier in my life because he was there with me in some way. I was never really alone. I had a partner. I had a true, great friend. And I think if you can have a true friend in your life that’s the greatest gift. But he’s gone somewhere ahead of me now, and he went way too fucking soon, and the gift he left behind is a New Feeling for me, a pain I cannot express or articulate but rather try to displace here in words, words, words that do nothing. I miss you Nick.

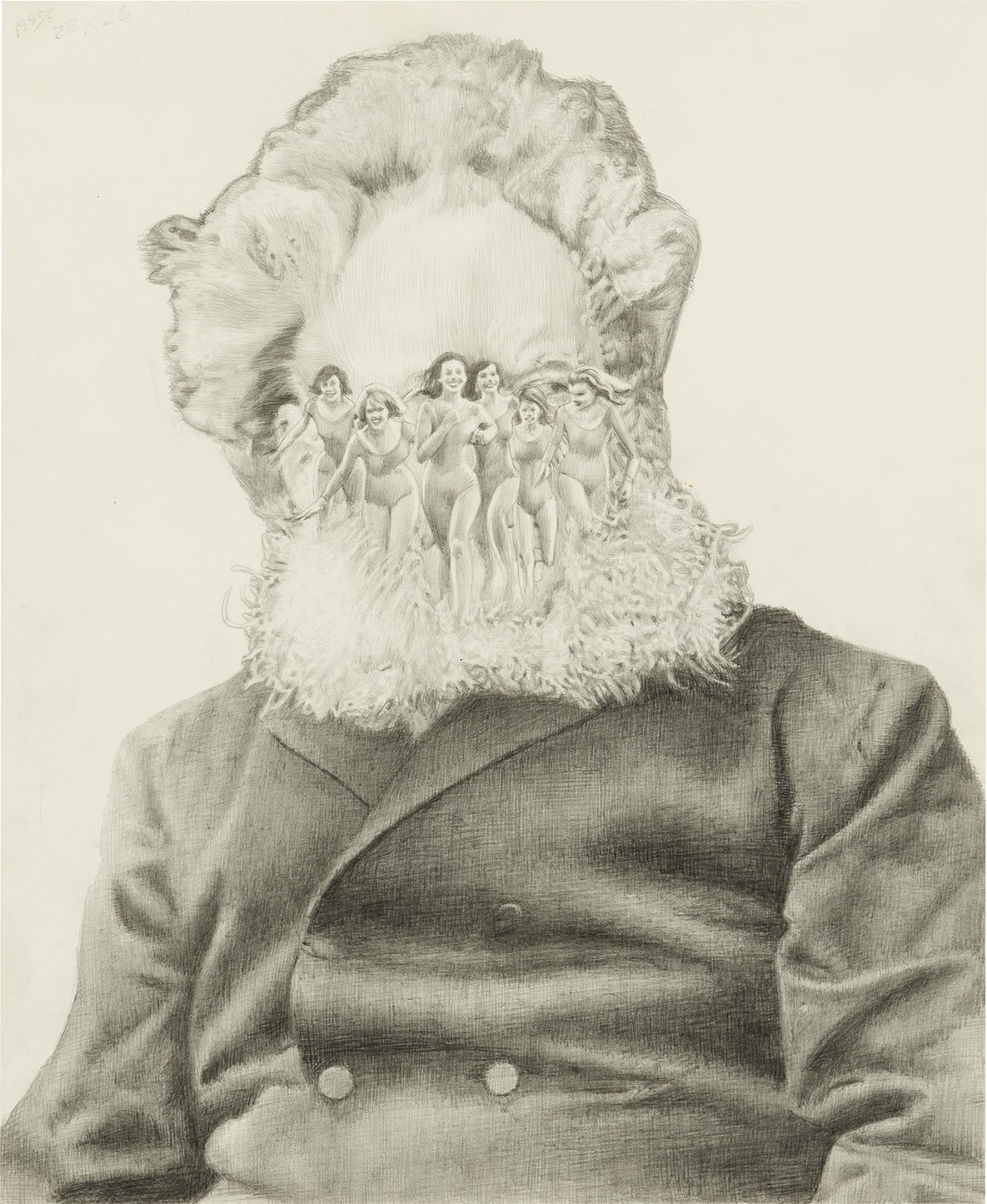

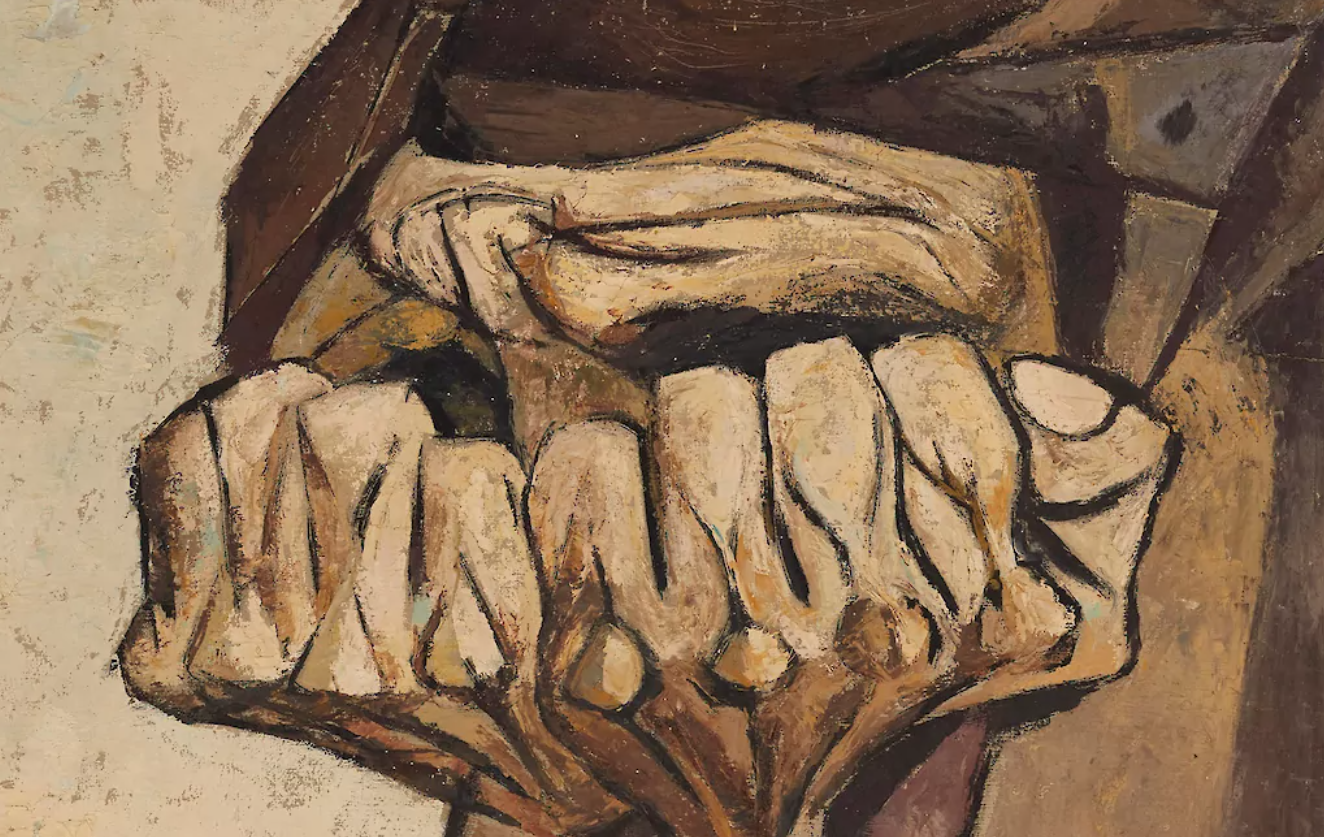

Couragemodell(a), 2022 by Giulia Andreani (b. 1985)

Couragemodell(a), 2022 by Giulia Andreani (b. 1985)