I. In this riff, Chapters 130-132 of Moby-Dick.

II. Ch. 130, “The Hat.”

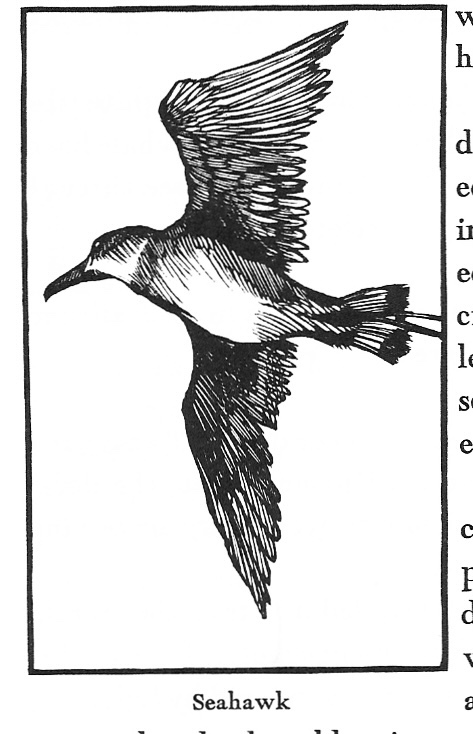

In which Ahab’s hat is stolen by “one of those red-billed savage sea-hawks which so often fly incommodiously close round the manned mast-heads of whalemen in these latitudes,” and the crew reads it, almost to a man, as an ill omen.

At the chapter’s outset, our Ishmael is in a meta-textual mood, pushing the quest’s doom into the foreground. He tells us that “all other whaling waters [are] swept” — we are in the penultimate triplet chapters:

In this foreshadowing interval too, all humor, forced or natural, vanished. Stubb no more strove to raise a smile; Starbuck no more strove to check one. Alike, joy and sorrow, hope and fear, seemed ground to finest dust, and powdered, for the time, in the clamped mortar of Ahab’s iron soul.

III. Ahab and Fedallah (who has foretold the doom of the ship he crews on) both keep to the deck at all times. Ahab declares that he will take the nailed doubloon, omphalos of both ship and novel — “‘I will have the first sight of the whale myself,’—he said. ‘Aye! Ahab must have the doubloon.'” Fedallah is a silent impenetrable gaze: “his wan but wondrous eyes did plainly say—We two watchmen never rest.”

IV. Ahab, as I’ve contended so many times, is monocular reader. Our one-legged monomaniacal despot of a captain can only watch and read for his dread mission. Unlike diverse, large-hearted Ishmael, there is no diversity in Ahab’s gaze/reading. He reads for one purpose, and all signs are symbols portending the fulfillment of that purpose.

As the sea-hawk approaches, Ahab’s gaze is upon the sea, not heavenward. We learn that the sea-hawk,

darted a thousand feet straight up into the air; then spiralized downwards, and went eddying again round his head.

But with his gaze fixed upon the dim and distant horizon, Ahab seemed not to mark this wild bird; nor, indeed, would any one else have marked it much, it being no uncommon circumstance; only now almost the least heedful eye seemed to see some sort of cunning meaning in almost every sight.

The crew of The Pequod reads the event as the foreshadow of disaster, whether the spectacle is simply a dark omen—the leader’s crown revoked from upon high—or simply the physical reality of their captain losing his hat because his attention was focused in only one direction.

V. Ch. 131, “The Pequod Meets the Delight.”

In which The Pequod encounters its last meeting with another ship—and another Nantucket ship—a “most miserably misnamed” The Delight:

Upon the stranger’s shears were beheld the shattered, white ribs, and some few splintered planks, of what had once been a whale-boat; but you now saw through this wreck, as plainly as you see through the peeled, half-unhinged, and bleaching skeleton of a horse.

I mean, c’mon. White ribs, bleaching skeleton of a horse, etc. It’s really the seeing through in the previous paragraph I’m interested in. Our Ishmael attends the world with the perspective of a ghost who sees through the world’s wreck.

VI. Ahab repeats his famous question (for the last time):

“Hast seen the White Whale?”

“Look!” replied the hollow-cheeked captain from his taffrail; and with his trumpet he pointed to the wreck.

“Hast killed him?”

“The harpoon is not yet forged that ever will do that,” answered the other, sadly glancing upon a rounded hammock on the deck, whose gathered sides some noiseless sailors were busy in sewing together.

Ahab shows off the harpoon he forged with Perth but captain and crew of The Delight remain morosely unimpressed. They bury at sea the last of five sailors they lost in battle with Moby Dick—the other four bodies were lost in the fight.

Ahab turns away from the scene.

And yet—

As Ahab now glided from the dejected Delight, the strange life-buoy hanging at the Pequod’s stern came into conspicuous relief.

“Ha! yonder! look yonder, men!” cried a foreboding voice in her wake. “In vain, oh, ye strangers, ye fly our sad burial; ye but turn us your taffrail to show us your coffin!”

Again—it’s an overdetermined affair, this Moby-Dick.

Show us your coffin!

VII. Ch. 132, “The Symphony.”

The whole thing is about to collapse.

In which Starbuck almost convinces Ahab to change course and save the souls of The Pequod.

“The Symphony” is another sad, sad chapter. “It was a clear steel-blue day,” the chapter begins, and then unfolds in short descriptions of pacific beauty. We are reminded of the peaceful air about The Pequod—that the violent rage at the heart of the novel is carried there by men, by their chieftan Ahab. But the dumb world will not attend our own woes:

Oh, immortal infancy, and innocency of the azure! Invisible winged creatures that frolic all round us! Sweet childhood of air and sky! how oblivious were ye of old Ahab’s close-coiled woe!

Again, Ishmael portrays Ahab in a sympathetic cast.

VIII. Ahab monologues at Starbuck, a sympathetic ear. He laments the forty years he’s spent asea:

Oh, Starbuck! it is a mild, mild wind, and a mild looking sky. On such a day—very much such a sweetness as this—I struck my first whale—a boy-harpooneer of eighteen! Forty—forty—forty years ago!—ago! Forty years of continual whaling! forty years of privation, and peril, and storm-time! forty years on the pitiless sea! for forty years has Ahab forsaken the peaceful land, for forty years to make war on the horrors of the deep! Aye and yes, Starbuck, out of those forty years I have not spent three ashore.

Are these Ahab’s last rites? A sad confession before the crack of doom (with those mythic numbers foregrounded, forty and three)? I think so.

(And, as always—

How does Ishmael witness this dialogue?)

IX. But Ahab’s confession does not lead to redemption. Language carries him away, and as always the ineffable nearly overwhelms him—he contests the unnameable:

What is it, what nameless, inscrutable, unearthly thing is it; what cozening, hidden lord and master, and cruel, remorseless emperor commands me; that against all natural lovings and longings, I so keep pushing, and crowding, and jamming myself on all the time; recklessly making me ready to do what in my own proper, natural heart, I durst not so much as dare? Is Ahab, Ahab? Is it I, God, or who, that lifts this arm? But if the great sun move not of himself; but is as an errand-boy in heaven; nor one single star can revolve, but by some invisible power; how then can this one small heart beat; this one small brain think thoughts; unless God does that beating, does that thinking, does that living, and not I.

Ahab the philosopher is a thing of despair:

By heaven, man, we are turned round and round in this world, like yonder windlass, and Fate is the handspike. And all the time, lo! that smiling sky, and this unsounded sea!

Starbuck, “blanched to a corpse’s hue with despair,” steals away. But Fedallah remains at his unvacant post, eyes focused on the water.