I. In this riff, Chapters 91, 92, and 93 of Moby-Dick.

II. Ch. 91, “The Pequod Meets The Rose-bud.”

Stubb stars in this humorous chapter in which The Pequod encounters a French vessel which is towing a pair of “what the fishermen call a blasted whale, that is, a whale that has died unmolested on the sea, and so floated an unappropriated corpse.” The smell from these two dead whales is awful. (Ish claims the odor is “worse than an Assyrian city in the plague, when the living are incompetent to bury the departed.”)

We soon learn the French ship bears an ironic name: “Bouton de Rose,”—Rose-button, or Rose-bud; and…this was the romantic name of this aromatic ship.”

Stubb hails the ship to ask Ahab’s famous question to all the ships The Pequod encounter, but the The Rose-bud has not seen the White Whale. Ahab leaves off, letting Stubb take over the chapter with his cruel comedy:

He now perceived that the Guernsey-man, who had just got into the chains, and was using a cutting-spade, had slung his nose in a sort of bag.

“What’s the matter with your nose, there?” said Stubb. “Broke it?”

“I wish it was broken, or that I didn’t have any nose at all!” answered the Guernsey-man, who did not seem to relish the job he was at very much. “But what are you holding yours for?”

“Oh, nothing! It’s a wax nose; I have to hold it on. Fine day, ain’t it? Air rather gardenny, I should say; throw us a bunch of posies, will ye, Bouton-de-Rose?”

“What in the devil’s name do you want here?” roared the Guernsey-man, flying into a sudden passion.

The Guernsey-man is irritated because his captain knows nothing of whales and refuses to discard the rotten animals, which his crew understand to be worthless. Stubb, however, thinks that one of the whales might be full of ambergris, a valuable substance, and he hatches a cunning plan to get the whale for himself. Stubb enlists the Gurnsey-man’s help in his plan: Stubb will appear as an expert witness on whales to The Rose-bud’s captain (ironically, a former perfumier)–only the captain speaks no English—so the Gurnsey-man will translate. However, the Gurnsey-man will simply say whatever he wants (namely, that they should cut the whales loose).

The scene plays out in comedy that I think still holds up today:

“What shall I say to him first?” said he.

“Why,” said Stubb, eyeing the velvet vest and the watch and seals, “you may as well begin by telling him that he looks a sort of babyish to me, though I don’t pretend to be a judge.”

“He says, Monsieur,” said the Guernsey-man, in French, turning to his captain, “that only yesterday his ship spoke a vessel, whose captain and chief-mate, with six sailors, had all died of a fever caught from a blasted whale they had brought alongside.”

Upon this the captain started, and eagerly desired to know more.

“What now?” said the Guernsey-man to Stubb.

“Why, since he takes it so easy, tell him that now I have eyed him carefully, I’m quite certain that he’s no more fit to command a whale-ship than a St. Jago monkey. In fact, tell him from me he’s a baboon.”

The scene continues in this line, with Stubb repeatedly insulting the captain who remains unaware of his abuse. When the captain offers Stubb a glass of wine to thank him for his advice, he replies thus:

“Thank him heartily; but tell him it’s against my principles to drink with the man I’ve diddled. In fact, tell him I must go.”

“He says, Monsieur, that his principles won’t admit of his drinking; but that if Monsieur wants to live another day to drink, then Monsieur had best drop all four boats, and pull the ship away from these whales, for it’s so calm they won’t drift.”

Stubb makes off with the whale and digs into it with his spade. He hits gold:

“I have it, I have it,” cried Stubb, with delight, striking something in the subterranean regions, “a purse! a purse!”

Dropping his spade, he thrust both hands in, and drew out handfuls of something that looked like ripe Windsor soap, or rich mottled old cheese; very unctuous and savory withal. You might easily dent it with your thumb; it is of a hue between yellow and ash colour. And this, good friends, is ambergris, worth a gold guinea an ounce to any druggist.

III. Stubb is the star of “The Pequod Meets The Rose-bud.” The chapter showcases his wit, and affords him all the best lines—lines a far cry from Ahab’s Shakespearean mode.

But this particular chapter also underlines my suspicion that Stubb is the villain of Moby-Dick. He’s cruel and greedy, duplicitous and hardhearted. He’s the opposite of largehearted Ishmael. Stubb has shown his double-edged comic cruelty earlier in the novel—most notably in the way he bullies his boat’s crew with sweethearted insults, but also in Ch. 64, “Stubb’s Supper,” when he plays cruel fun on Fleece, the Black cook of The Pequod. Stubb’s cruel avarice comes to a head in Ch. 93, “The Castaway.” But let’s first attend to Ch. 92, “Ambergris.”

IV. Ch. 92, “Ambergris.”

“Who would think, then, that such fine ladies and gentlemen should regale themselves with an essence found in the inglorious bowels of a sick whale!” Ishmael ponders near the beginning of this short chapter, which again riffs on a major theme of Moby-Dick; namely, how every thing earthly (and unearthly) finds its definition in its opposition.

V. Ch. 93, “The Castaway.”

Right.

So. Anyway. Per point III—I think I was arguing that Stubb is something of an asshole. He’s a bully, a bad boss, and despite the genial empathy in Ishmael’s voice (Melville’s voice?) that extends to all the horribles of The Pequod, he does not acquit himself well in “The Castaway.”

Ish sets the tragic scene from the outset:

It was but some few days after encountering the Frenchman, that a most significant event befell the most insignificant of the Pequod’s crew; an event most lamentable; and which ended in providing the sometimes madly merry and predestinated craft with a living and ever accompanying prophecy of whatever shattered sequel might prove her own.

In other words: The fate of poor Pip, the Black cabin boy, prefigures the fate of all the crew of the damned Pequod—-

and—

VI. (And, parenthetically—

I’ve been falling asleep to an audiobook of Cormac McCarthy’s novel Blood Meridian, which many many many folks have pointed out follows Moby-Dick, both rhetorically and thematically

(I mean hey, consider those opening lines:

“Call me Ishmael”

“See the child.

)

And anyway, I sort of dip into Blood Meridian in random places, finding concurrent moments, motifs, intersections—

And in the Tarot scene of Blood Meridian, the Judge tells the Black Jackson that “In your fortune lie our fortunes all” — an echo here of the fate of poor Pip.

)

VII. And anyway,

—So, “in the ambergris affair Stubb’s after-oarsman chanced so to sprain his hand, as for a time to become quite maimed; and, temporarily, Pip was put into his place.”

Pip was put into his place.

Pip freaks out and jumps from the boat his first time, a jump that results in the loss of a whale. Sadistic Stubb is stern (and more than racist) in his rebuke:

“Stick to the boat, Pip, or by the Lord, I won’t pick you up if you jump; mind that. We can’t afford to lose whales by the likes of you; a whale would sell for thirty times what you would, Pip, in Alabama. Bear that in mind, and don’t jump any more.” Hereby perhaps Stubb indirectly hinted, that though man loved his fellow, yet man is a money-making animal, which propensity too often interferes with his benevolence.

(Old Ishmael (and Old Melville) — what’s with the verb hinted there?)

And so and well—

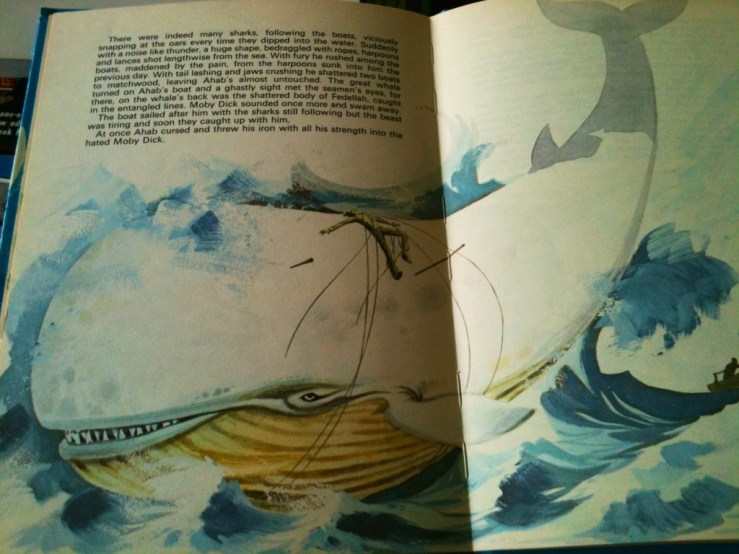

But we are all in the hands of the Gods; and Pip jumped again. It was under very similar circumstances to the first performance; but this time he did not breast out the line; and hence, when the whale started to run, Pip was left behind on the sea, like a hurried traveller’s trunk. Alas! Stubb was but too true to his word. It was a beautiful, bounteous, blue day; the spangled sea calm and cool, and flatly stretching away, all round, to the horizon, like gold-beater’s skin hammered out to the extremest. Bobbing up and down in that sea, Pip’s ebon head showed like a head of cloves. No boat-knife was lifted when he fell so rapidly astern. Stubb’s inexorable back was turned upon him; and the whale was winged. In three minutes, a whole mile of shoreless ocean was between Pip and Stubb. Out from the centre of the sea, poor Pip turned his crisp, curling, black head to the sun, another lonely castaway, though the loftiest and the brightest.

Ishmael understands the incredible existential loss of being castaway in the wide waste of the sea:

…the awful lonesomeness is intolerable. The intense concentration of self in the middle of such a heartless immensity, my God! who can tell it?

Poor Pip goes mad. His fate will be the fate of the company proper.

And if Ishmael’s sympathy sympathizes the victim, so too does it sympathize the villain—-

For the rest, blame not Stubb too hardly. The thing is common in that fishery; and in the sequel of the narrative, it will then be seen what like abandonment befell myself.

—and yet that sympathy is an empathetic prefiguring gust of our narrator Ish’s ultimate fate.