I. In this riff, Chapter 135, “The Chase—Third Day” and the Epilogue of Moby-Dick.

The beginning of the end begins, “The morning of the third day dawned fair and fresh” — we are in the tranquil pacified Pacific, beautiful blue, the calm site of a coming calamity.

II. After calling for news of the White Whale, Ahab riffs to himself on the wind. The wind is an apparently concrete force that operates with abstract agency. The wind is a kind of fate, an invisible entity that both propels and repels objects of the phenomenal world:

Would now the wind but had a body; but all the things that most exasperate and outrage mortal man, all these things are bodiless, but only bodiless as objects, not as agents. There’s a most special, a most cunning, oh, a most malicious difference! And yet, I say again, and swear it now, that there’s something all glorious and gracious in the wind.

III. Ahab glimpses his folly: “I’ve oversailed him,” he mutters about Moby Dick, continuing, “How, got the start? Aye, he’s chasing me now; not I, him—that’s bad; I might have known it, too. Fool!”

The fool there is of course a bit of self-talk Ahab directs to his self-same self.

IV. This final chapter is full of self-talk. Starbuck’s inner monologue turmoils, “I misdoubt me that I disobey my God in obeying him!” Ahab swears to meet Moby Dick, “Forehead to forehead…this third time”; we enter the final private thoughts of Stubb and Flask (but never the pagan harpooneers).

As always, my question remains—

How does Ishmael bear witness to these voices?

V. In a potent soliloquy, Ahab’s sentimentality takes over. He addresses the vast ocean, “the same to Noah as to me.” He seems to portend his own demise, and is distracted momentarily by the “lovely leewardings” that “must lead somewhere—to something else than common land, more palmy than the palms.” But he won’t escape: “Leeward! the white whale goes that way; look to windward, then; the better if the bitterer quarter. But good bye, good bye, old mast-head!”

By the end of the soliloquy Ahab is again convinced — or maybe not wholly convinced, but nevertheless affirming — of his impending victory. He addresses the masthead anew: “We’ll talk to-morrow, nay, to-night, when the white whale lies down there, tied by head and tail.”

VI. Ahab rejects two final calls to remain and retreat. The first is Starbuck’s:

“Some men die at ebb tide; some at low water; some at the full of the flood;—and I feel now like a billow that’s all one crested comb, Starbuck. I am old;—shake hands with me, man.”

Their hands met; their eyes fastened; Starbuck’s tears the glue.

Starbuck’s tears the glue! What a line!

The second entreaty I take to be Ahab’s other first mate, the mad cabinboy Pip:

“Oh, my captain, my captain!—noble heart—go not—go not!—see, it’s a brave man that weeps; how great the agony of the persuasion then!”

“Lower away!”—cried Ahab, tossing the mate’s arm from him. “Stand by the crew!”

“The sharks! the sharks!” cried a voice from the low cabin-window there; “O master, my master, come back!” But Ahab heard nothing; for his own voice was high-lifted then; and the boat leaped on.

Ahab rejects all fellow-feeling here. His monomaniacal voice overtakes all bandwidth, drowning out any sensation of otherness.

VII. The sharks follow Ahab’s boat like “vultures hover over the banners of marching regiments in the east”; as usual, Melville is not shy about slathering on the foreshadowing. He enlists Starbuck’s help; the Christian mate remarks that this, “the third evening,” be “the end of that thing—be that end what it may.”

VIII. Meanwhile, Ahab repeats pagan Fedallah’s pagan prophecy: “Drive, drive in your nails, oh ye waves! to their uttermost heads drive them in! ye but strike a thing without a lid; and no coffin and no hearse can be mine:—and hemp only can kill me! Ha! ha!”

Those dashes, those exclamations—that madness!

IX. Moby Dick then resurfaces, all veils, rainbows, milk:

A low rumbling sound was heard; a subterraneous hum; and then all held their breaths; as bedraggled with trailing ropes, and harpoons, and lances, a vast form shot lengthwise, but obliquely from the sea. Shrouded in a thin drooping veil of mist, it hovered for a moment in the rainbowed air; and then fell swamping back into the deep. Crushed thirty feet upwards, the waters flashed for an instant like heaps of fountains, then brokenly sank in a shower of flakes, leaving the circling surface creamed like new milk round the marble trunk of the whale.

Our boy Moby Dick sets to violence, dashing the boats of Daggoo and Queequeg.

X. The violent spectacle culminates in the most gruesome imagery within Moby-Dick. We learn the fated fate of fated Fedallah:

Lashed round and round to the fish’s back; pinioned in the turns upon turns in which, during the past night, the whale had reeled the involutions of the lines around him, the half torn body of the Parsee was seen; his sable raiment frayed to shreds; his distended eyes turned full upon old Ahab.

XI. Ahab commands his sailors to remain rowing after the White Whale, despite the downed lieutenants and zombified harpooneer. He threatens them:

Down, men! the first thing that but offers to jump from this boat I stand in, that thing I harpoon. Ye are not other men, but my arms and my legs; and so obey me.—

Ahab, who has repeated the idea that his mates are but mechanical things throughout the novel, here spells out his distance from human sympathy, his complete fascistic capitulation. “Ye are not other men” is the exact opposite of the Gospels’ injunction to do unto others. Ahab fails Starbuck’s moral test—and Ishmael’s.

XII. Ahab sees his pagan harpooneers and wrecked mates return to The Pequod to repair boats and rearm:

…he saw Tashtego, Queequeg, and Daggoo, eagerly mounting to the three mast-heads; while the oarsmen were rocking in the two staved boats which had but just been hoisted to the side, and were busily at work in repairing them. One after the other, through the port-holes, as he sped, he also caught flying glimpses of Stubb and Flask, busying themselves on deck among bundles of new irons and lances. As he saw all this; as he heard the hammers in the broken boats; far other hammers seemed driving a nail into his heart. But he rallied. And now marking that the vane or flag was gone from the main-mast-head, he shouted to Tashtego, who had just gained that perch, to descend again for another flag, and a hammer and nails, and so nail it to the mast.

I’ve quoted at length because I think our eyes should be trained on Tashtego, the Native American twice now denied his proper place. He was the first to raise a whale on The Pequod’s voyage (denied by Stubb), and the first to raise Moby Dick (denied by Ahab). Tash will be the last to go down with the ship, nailing a new banner to its highest mast.

XIII. Meanwhile, the sharks chew and chomp at the oarsmen’s oars in Ahab’s whaleboat, to the point “that the blades became jagged and crunched, and left small splinters in the sea, at almost every dip.”

They row on.

XIV. Ahab’s boat comes about and he darts “his fierce iron, and his far fiercer curse into the hated whale.” Three of his oarsmen are knocked from the boat, and only two return, although the one who bobs asea is reported “still afloat and swimming.”

This third castaway is Ishmael.

XV. Moby Dick then attacks The Pequod, “bethinking it—it may be—a larger and nobler foe.”

(“‘The whale! The ship!’ cried the cringing oarsmen.”)

XVI. The White Whale destroys The Pequod, and Melville takes us into the last lungfuls of language from the three mates, Starbuck, Stubb, and Flask. These are mini-monologues that Moby Dick’s ensuing vortex will swamp to oblivion.

“My God, stand by me now!” beseeches Starbuck; “Stand not by me, but stand under me, whoever you are that will now help Stubb,” Stubb non-prays, before praying against this “most mouldy and over salted death”— he’d prefer “cherries! cherries! cherries!” And Flask? “Cherries? I only wish that we were where they grow.” Poor Flask then think of his dear mama, before the ship fails.

XVII. Moby Dick wrecks The Pequod. The crew (in Ishmael’s telling) bears witness:

…all their enchanted eyes intent upon the whale, which from side to side strangely vibrating his predestinating head, sent a broad band of overspreading semicircular foam before him as he rushed. Retribution, swift vengeance, eternal malice were in his whole aspect, and spite of all that mortal man could do, the solid white buttress of his forehead smote the ship’s starboard bow, till men and timbers reeled. Some fell flat upon their faces. Like dislodged trucks, the heads of the harpooneers aloft shook on their bull-like necks. Through the breach, they heard the waters pour, as mountain torrents down a flume.

XVIII. As Ahab watches the disaster, he comes to understand Fedallah’s prophecy: “The ship! The hearse!—the second hearse!” cried Ahab from the boat; “its wood could only be American!”

XIX. And then—

Ahab’s final speech:

Oh, now I feel my topmost greatness lies in my topmost grief. Ho, ho! from all your furthest bounds, pour ye now in, ye bold billows of my whole foregone life, and top this one piled comber of my death! Towards thee I roll, thou all-destroying but unconquering whale; to the last I grapple with thee; from hell’s heart I stab at thee; for hate’s sake I spit my last breath at thee. Sink all coffins and all hearses to one common pool! and since neither can be mine, let me then tow to pieces, while still chasing thee, though tied to thee, thou damned whale! Thus, I give up the spear!

Ahab is knocked from the boat, and hanged in hemp and hate.

XX. The Pequod sinks, but

the pagan harpooneers still maintained their sinking lookouts on the sea. And now, concentric circles seized the lone boat itself, and all its crew, and each floating oar, and every lance-pole, and spinning, animate and inanimate, all round and round in one vortex, carried the smallest chip of the Pequod out of sight.

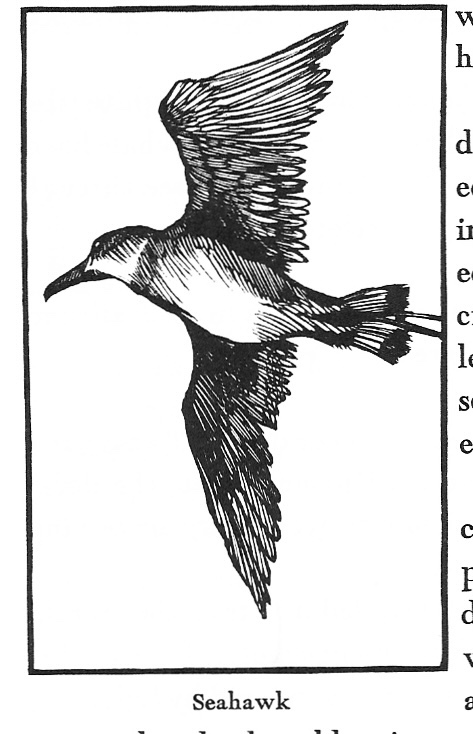

The final image is devastating: Tashtego nails a seahawk to the mast. Again, forgive me for quoting at length:

…as the last whelmings intermixingly poured themselves over the sunken head of the Indian at the mainmast…a red arm and a hammer hovered backwardly uplifted in the open air, in the act of nailing the flag faster and yet faster to the subsiding spar. A sky-hawk that tauntingly had followed the main-truck downwards from its natural home among the stars…now chanced to intercept its broad fluttering wing between the hammer and the wood; and simultaneously feeling that ethereal thrill, the submerged savage beneath, in his death-gasp, kept his hammer frozen there; and so the bird of heaven, with archangelic shrieks, and his imperial beak thrust upwards, and his whole captive form folded in the flag of Ahab, went down with his ship, which, like Satan, would not sink to hell till she had dragged a living part of heaven along with her, and helmeted herself with it.

What an image!

(I have nothing to add here.)

XXI (Excepting, I would add: I think Melville loads so much in this near-final image of his big book. There are only two paragraphs after this one: a scant sentence that’s basically an exhalation from the image of a submerged Tashtego nailing a hawk to the mast of the sinking Pequod—and then the Epilogue. The Pequod takes its name from an extinct Native American tribe. Tashtego is doubly-denied his due as the First to raise whale. Melville seems to point back to America’s founding as a genocidal project here. I probably need to reread the book again, I now realize. Or maybe read some commenters on this matter that I’ve yet to read. I hate to stick this thought in parentheses, as it’s the thing that interests me the most at the end of this reread—Tashtego the Indian, I mean.)

XXII. And so well the end of the end, the Epilogue.

Here it is in the Arion Press edition I read this time through:

XXIII. Ishmael survives, “floating on the margin of the ensuing scene, and in full sight of it.”

What a position! To be both marginal and omnipresent, both at edge and center to the drama, comedy, tragedy of it all!

The notation from the Book of Job is everything here—the disaster is only a disaster if there is one to bear witness to it. Otherwise, disaster is simply a phenomenological event in nature—random, stochastic, energy, mass, and matter moving without meaning.

Ahab pretends at a great searcher for meaning, but he fixes his search on vengeance. “Madness!” Starbuck chides (if Starbuck could chide) — “To be enraged with a dumb thing, Captain Ahab, seems blasphemous.” Ahab has read too deep, read too twisted—he’s a bad reader, a mutant reader, an overreader—but he’s failed repeatedly to read the souls and faces of his fellows.

XXIV. The final curse and blessing is upon Ishmael though. He names himself at the novel’s famous outset — “Call me Ishmael” — a call that likens him to Hagar’s outcast son. At its end, he likens himself to another outcast, “another Ixion,” all the while circling into a vortex of nature, meaning, language—all the forces that would swallow him. (He’s Melville’s maddened howl here.)

Ishmael floats on “a soft and dirgelike main,” bobbing alive on Queequeg’s coffin, the strange lifebuoy of his strange bedfellow, until he’s saved by The Rachel—the ship Ahab had earlier denied—which still cruises for a lost son. He is not the lost son, but he has been lost, and is here saved by The Rachel’s “retracing search after her missing children” — a retracing, a rereading, a rewriting — one that surfaces the wailing of only another orphan.