What are the problems of Herman Melville’s story “Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street”?

This question seems like a bad starting place.

Let me share an anecdote instead.

—I was in the tenth grade the first time I read “Bartleby.”

At the time, I thought I was a teacher’s dream—a sharp reader, someone who loved English class, someone with opinions about the texts we read. Lots and lots of opinions. In retrospect, I realize that I was a nightmare for poor Ms. Hall, a wonderful teacher who I’m sure dreaded our meetings (there were like 15 guys in the class, all unruly).

Simply put, I didn’t want to do things her way.

So she gave me a copy of Billy Budd, Sailor and Other Stories and told me to read “Bartleby,” suggesting that there was something I might learn from it.

I don’t know if backfired is exactly the right term for the results of this experiment. I do know that “Bartleby” offered me a brilliant retort—a literary allusion!—to refuse any task I didn’t feel like undertaking in 10th grade English:

“I would prefer not to.”

—While we’re here—

“I would prefer not to”

So, this is clearly one of the problems of “Bartleby,” if not the core problem condensed into one utterance: Why would? Why the conditional?

Consider, vs. I prefer not to, a constative (or maybe even performative) utterance.

But Bartleby “would prefer not to.”

Contrast this with the imperative must that the narrator employs:

At the expiration of that period, I peeped behind the screen, and lo!

Bartleby was there.I buttoned up my coat, balanced myself; advanced slowly towards him, touched his shoulder, and said, “The time has come; you must quit this place; I am sorry for you; here is money; but you must go.”

“I would prefer not,” he replied, with his back still towards me.

“You must.”

He remained silent.

Now I had an unbounded confidence in this man’s common honesty. He had frequently restored to me sixpences and shillings carelessly dropped upon the floor, for I am apt to be very reckless in such shirt-button affairs. The proceeding then which followed will not be deemed extraordinary.

“Bartleby,” said I, “I owe you twelve dollars on account; here are thirty-two; the odd twenty are yours.—Will you take it?” and I handed the bills towards him.

These brief lines perhaps serve to summarize Melville’s tale.

We see here the basic plot—our titular scrivener will not leave the lawyer’s office after weeks of refusing (although refusing is not quite the right word) to work.

We also see here what I take to be the theme of “Bartleby,” the strange ethical position Bartleby’s (conditional) would prefer not to places the narrator’s (imperative) must set against the moral backdrop of do unto others: namely, an impossible ethical position for a Wall Street lawyer especially and most of us in general.

And “Bartleby,” as you’ll no doubt recall, is in some ways Melville trying to work out the problems of Matthew 25:35-39—

For I was an hungred, and ye gave me meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink: I was a stranger, and ye took me in:

Naked, and ye clothed me: I was sick, and ye visited me: I was in prison, and ye came unto me.

Then shall the righteous answer him, saying, Lord, when saw we thee an hungred, and fed thee? or thirsty, and gave thee drink?

When saw we thee a stranger, and took thee in? or naked, and clothed thee?

Or when saw we thee sick, or in prison, and came unto thee?

Perhaps our narrator tries to do these things—tries to feed and clothe and help this stranger Bartleby—but he can’t. Because Bartleby won’t give him an agency to relate to.

Because Bartleby’s utterance “I would prefer not to” denies the performative or constantive or declarative—indeed, it suspends or disrupts its own conditionality, the relation of the subject to its predicate verb.

Or consider one of Bartleby’s only other lines: “What is wanted?” His grammar again suspends agency, disrupts the notion of a stable I (let alone objective case me) that the narrator can interface with, dictate to, interrogate, see his own narcissistic reflection in).

—Hang on though, I was telling an anecdote. It was about the first time I read “Bartleby,” when I was fourteen or fifteen. This is the book:

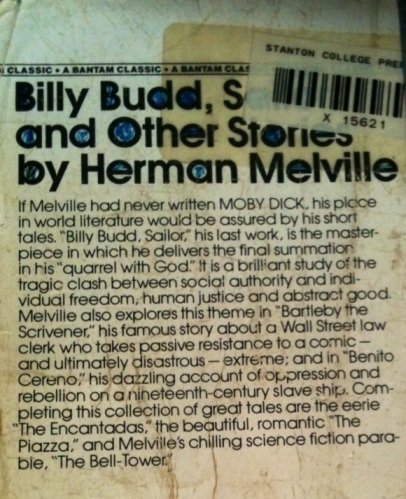

I stole it of course, or never returned it. Yes, that’s duct tape on its side. It is more or less falling apart. Here’s the back, barcode and all.

Over the years, like many readers, I returned many times to “Bartleby,” reading it again in high school, then in college, then in grad school. I read it unassigned too, of course—when I read Kafka and it recalled itself to me, and when I read Moby-Dick for the first time. I read it when compelled. And then I read it with my own students. (I read most of the other stuff in the collection too, of course — Billy Budd and then later (why so much later?!) Benito Cereno).

I scrawled through so much of the book that my annotations are basically worthless, virtually everything underlined or circled:

So we butt up against the problems of “Bartleby”—the problems of interpretation. How to figure an eponymous “hero” who is no more than a phantom, a trace, a lack? How to hash out a narrator who presents himself in relatively admirable terms and yet is so clearly an ethical failure? Why oh why would Bartleby prefer not to? Is the story a tragedy or a comedy? Does it present a world with rules, codes, ethics, or is all absurd here—nihilistic even? Is Bartleby a Christ figure? An ascetic monk? A ghost? Is the story just about Melville’s own anger over the poor reception of Pierre? How much of contemporary transcendentalist thought can we find in the story?

—Slight shift:

The kind people of Melville House were sporting enough to send a copy of “Bartleby” my way. The book is part of their HybridBooks project; these books offer “digital illuminations” along with traditional (uh, paper) books.

I’d requested a HybridBook—any one of them, really—because I now read about half the time on a Kindle Fire—so I was particularly interested in what a “hybrid” had to offer. What is the reading experience like?

First, the book itself is part of Melville House’s Art of the Novella series—beautiful, minimal design with French flaps. I read it on my porch the afternoon it arrived, enjoying its pristine, white, unmarked pages. Then, I checked out the “Digital Illuminations.”

The illuminations are available in several device-specific options, all easy to download with the QRC that comes with the book. I read most of the illuminations on my Kindle, but I also put them on my iPhone and my laptop. I had originally intended this post to be specifically about the digital illuminations, but hell, “Bartleby” is just too damn freighted a read for me at this point. Anyway, there’s a lot of good stuff in there, including “The Transcendentalist” by Ralph Waldo Emerson, selections from Jonathan Edwards and Joseph Priestly, Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience,” and several excerpts from Melville himself, including letters, other books, and reviews. What I found must, uh, illuminating was “Of Some of the Sources of Poetry Amongst Democratic Nations” from Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville. There are also illustrations, including a map; there’s even a recipe for ginger nuts. I wish that MH had included a digital copy of the book though. From a practical, concrete standpoint, I found it easier to switch between the free public domain version of “Bartleby” on my Kindle and MH’s illuminations than it would have been to pick up the physical book.

Now, to shift back (perhaps):

Do the digital illuminations help to answer or solve or address some of the problems of “Bartleby,” some of the issues posed above?

Should they?

—I suppose the hedging answer is yes and no.

The additional material illuminates some of the philosophical, political, historical, and even personal context for “Bartleby.” The material is edited with minimal intrusion, but with enough explication to clearly connect the various selections to Melville’s story. If I’m reading with my teacher hat on (this is a metaphor; there is no literal hat), I’d say you probably couldn’t do better than what Melville House has put together here. The digital illuminations provide a strong foundation for an informed reading, a range of texts that speak (obliquely or otherwise) to “Bartleby.”

Does it all add up to a deeper or richer understanding of “Bartleby”?

Should it?

—Well. No. And then no.

I mean, would we want a series of essays that would provide the missing pieces that would allow us to puzzle out “Bartleby”? Could we even trust such pieces, let alone trust ourselves to trust such pieces? Isn’t this strange uncertainty why “Bartleby” endures—and endures apart from Moby-Dick or Billy Budd, strange texts themselves, but also not nearly as confounding?

“Bartleby” simultaneously wriggles and plays dead; it burns with apparent wit but then reminds us that we might not be in on the joke. It is Kafkaesque thirty years before Kafka was even born. It shakes off its allegorical idiom the minute we think we might limn its contours. It makes us read it again because we cannot pin it down.

—But maybe you want to pin it down, tickle it, torture it, make it solve its problems (or at least respond, damn it!).

And maybe I claimed that “Bartleby” was about something—that it was about ethical relations, about duty to one’s fellows—especially when a fellow isn’t a fellow but rather the trace of a fellow, the idea of a fellow, a ghost.

So, look, here’s a take on it:

The narrator—let’s call him Lawyer—Lawyer, see he’s a dick, in the parlance of our times. He’s a dick because he doesn’t know that he’s a dick, which is one of the constituting factors of the ontological state of being a dick. He also does not want to see himself as being a dick (this is another factor in the ontological state of being a dick). He wants to see himself as a good guy, this Wall Street dickhead, but Bartleby won’t let him do that. Bartleby won’t even let him see himself at all: Bartleby doesn’t reflect back. He prefers not to.

Our Lawyer, see, he’s all buttoned up, he’s snug (these are his words). He tells us upfront that he possesses “a profound conviction that the easiest way of life is the best”; he repeatedly points out the way that people are “useful” to him (or to others). He sees no possibility of an ethics outside of usefulness; on top of that, he cannot see that he cannot see any possibility of an ethics based on anything but “usefulness” (or the negative economy of obstruction figured in Bartleby).

And ah Bartleby, ah humanity: One time model employee, once apparently free from the eccentricities that plague the Lawyer’s other scriveners, Turkey and Nippers. Machinelike.

Bartleby mechanically completes large quantities of copies without comment or complaint. But when asked to simply read in unison with Lawyer and his scriveners, Bartleby replies: “I would prefer not to.” Bartleby will not read with others—he is literally not on the same page as his colleagues.

Lawyer confronts Bartleby with his noncompliance; Bartleby repeats his mantra. Fuck mantra though because it’s not a mantra. It’s only repeated for Lawyer, to Lawyer, really, who can’t schematize/name/pin down Bartleby’s response. In fact, I would prefer not to so startles Lawyer that he says he’s “unmanned” by the words. So he rationalizes Bartleby’s odd response, internalizes it, paraphrases it, if you like.

And then Bartleby ceases to even do his copying work. Oh the anarchy! But wait, there’s not even anarchy. There’s not even protest. There’s just big nothing. But not even big nothing—instead the smallest nothing (which proves that big nothing is possible).

So Lawyer attempts to “help” Bartleby. Lawyer believes doing so is his “Christian duty.” And to know that this duty has been met, Lawyer needs Bartleby to be his echo. But Bartleby’s I prefer not to denies this narcissistic exchange. He empties his I of ego (shades of Emerson’s Transparent Eyeball).

Confused, Lawyer tries to pay off Bartleby. When that doesn’t work, Lawyer actually packs up and moves to a new office. But even here he can’t cut off Bartleby. The office’s landlord comes to Lawyer to remove Bartleby.

And when Bartleby refuses to leave the office he is taken to “the Tombs”—prison.

Here, Lawyer tries to provide comfort for Bartleby (hearken ye back to Matthew 25:35-39). He arranges for Bartleby to receive good food in the prison. Bartleby prefers not to eat though, and dies curled up in the fetal position during a visit by Lawyer.

Lawyer is the first reader of Bartleby. But like many readers of “Bartleby,” he is confused.

Lawyer’s confusion results from his need for safety—for ease, for comfort, for a snug, buttoned-upness—and that safety is bought through an affirmation of first-person experience: namely, in the affirmation of the self in the other. That security is bought through assimilating another person’s first-person perspective. But Bartleby is empty of I, of self, of ego.

Bartleby would prefer not to: He will not be ventriloquized: He will not echo: He will not read from the same script: He will not be “of use,” as Lawyer puts it.

So Bartleby dissipates and dissolves: He goes down in the Tombs: a ghost, and impossibility, presence coupled with absence.

— And the epilogue:

We all recall the epilogue, yes?

Lawyer offers up “one little item of rumor,” a morsel, a “vague report . . . that Bartleby had been a subordinate clerk in the Dead Letter Office at Washington.” The idea tears the narrator up inside: “Dead letters! does it not sound like dead men?”

For Lawyer, Bartleby is a dead letter, a failed letter.

Did Melville worry that “Bartleby” would be a failed letter? That it would not find an audience? That his work would not be delivered? If he did, it seems too then that Bartleby’s negations foreclose or reject this concern. Not sure of how to wrap up this riff, I’ll retreat to the safety of my title.

We find the final problems (in basic narrative chronology, that is) of “Bartleby” in its final line. Has Lawyer learned from his experience? Can he empathize, finally feel something for Bartleby beyond the confines of a perceived ethical duty? Is Bartleby a place holder for all humanity? Or is Bartleby in opposition to humanity? What does it mean—-

Ah Bartleby! Ah humanity!

?

[Ed. note–Biblioklept originally posted this riff in November of 2012. I’m running it again for Herman Melville’s 200th birthday.]