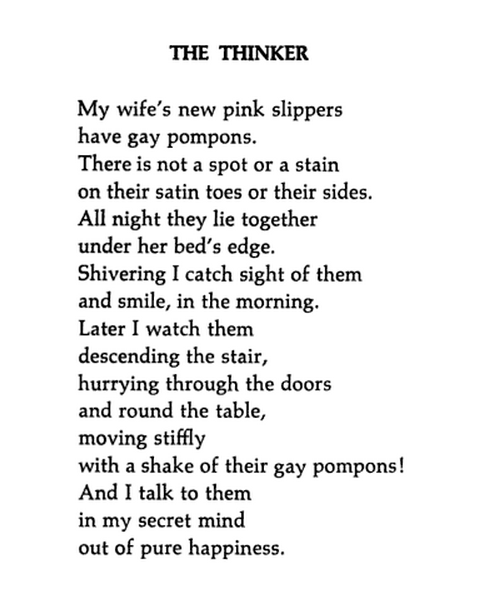

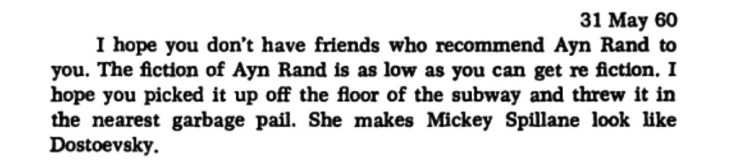

From a 1960 letter Flannery O’Connor wrote to her friend Maryat Lee. The letter is collected in The Habit of Being.

From a 1960 letter Flannery O’Connor wrote to her friend Maryat Lee. The letter is collected in The Habit of Being.

[Ed. note: The following citations come from one-star Amazon reviews of James Joyce’s Ulysses. To be clear, I think Ulysses is a marvelous, rewarding read. While one or two of the reviews are tongue-in-cheek, most one-star reviews of the book are from very, very angry readers who feel duped]

I can sum this book up in two words: “Ass Beating”.

What an awful book this is?

I bought this having been a huge fan of the cartoon series, but Mr Joyce has taken a winning formula and produced a prize turkey. After 20 pages not only had Ulysses failed to even board his spaceship, but I had no idea at all what on earth was going on. Verdict: Rubbish.

When an English/American writer try to explain his/her ideas about life(I mention ideas about meaning,purpose and philosophy of life)and when he/she try to do this with complicated ideas and long sentences(or like very short ones especially in this particular book);what his/her work become to is:A tremendous nonsense!!!

Thi’ got to be the worst, I- I – I mean the worst ever written book ever. Know why? ‘Cause he’ such a showoff, know what I MEAN? He’s ingenious I’ll giv’ ’em that, but ingenuity my friends tire and enervate. Get to the point and stick to it ‘s my motto.

This is one of those books that “smart” people like to “read.”

The grammar is so disjointed as to make it nearly impossible to read.

Ulysses is basically an unbridled attack on the very ideas of heroism, romantic love and sexual fulfillment, and objective literary expression.

What’s with all the foreign languages?

It has no real meaning.

It is a blasphemy that it ever was published.

Anyone who tells you they’ve read this so-called book all the way through is probably lying through their teeth.It is impossible to endure this torture.

A babbling, senseless tome upheld by “literary luminaries” who fear being cast into the tasteless bourgeois darkness for dissent? Yes, that’s the gist.

I discovered that the novel was not what I though it would be.

Joyce is an aesthetic bother of Marcel Duchamp (known for The Fountain, a urinal, now a museum piece) and John Cage (the composer of pieces for prepared piano, where the piano’s strings are mangled with trash.

Two positive things I can say about James Joyce is that he has a great sounding name and he gives wonderful titles to his works.

Ask yourself – are you going to enjoy a book that neccesitates your literature teacher lie next to you and explain its ‘sophistication’ to you ?

It’s the worst book which has ever been written.

Unless you really hate yourself, do not attempt to read this book.

The truth is this book stinks. For one thing it is vulgar, which, I hate to disappoint anyone, requires no talent at all. This is a talent any six year-old boy possesses.

The book is not so good, it is boring, it is a colection of words and a continuous experimentation of styles that, unhappily, do not mean anything to the meaning of the story; that is, the book’s language is snobbish and useless. Those who say that “love” such a writing are to be thought about as non-readers or as victims of a literary abnormality.

…the single most destructive piece of Literature ever written…

I’m all for challenging reads, but not for gibberish which academics persist in labeling erudition.

This book is extremely dull!!! My book club decided to read this book after one of the members visited the James Joyce tower in Ireland, which the author supposedly wrote part of the book in.

Ulysses is a failed novel because Joyce was a bad writer (shown by his other works).

In conclusion, Don’t read the book. Burn it hard. Do not let your children read the book—it will mutilate their brain cells.

Film footage of the first Bloomsday celebration (June 16, 1954)–a great find by Antoine Malette, who posted the video along with an account of the journey as told in Flann O’Brien: An Illustrated Biography. The film was shot by John Ryan, and shows an extremely inebriated Brian O’Nolan (aka Flann O’Brien) having to be helped around by pals Anthony Cronin and Patrick Kavanagh. We’re also treated to a scene of Kavanagh taking a piss with Joyce’s cousin Tom Joyce, a dentist who joined the merry band. (The scene will undoubtedly recall to you that marvelous moment in Ulysses when “first Stephen, then Bloom, in penumbra urinated“). The troupe didn’t quite finish their mission, getting sidetracked by booze and quarrels. Read the full account at Malette’s site.

Makes breakfast for his wife. Goes to the butcher. Goes to the post office. Goes to church. Goes to a chemist. Goes to a public bath. Goes to a funeral. Goes to a newspaper press. Goes to a locksmith to canvass an ad. Feeds some seagulls. Goes to a bar. Helps a blind man cross the street. Goes to the museum. Goes to to the library. Visits a bookseller. Window-shops. Goes to a restaurant. Listens to some live music. Writes a love letter. Goes to another bar. Nearly gets in a fight. Masturbates to a beautiful eighteen-year-old exhibitionist giving him a private show. Takes an alfresco nap. Takes up a collection for a widow. Goes to a hospital to visit a pregnant woman. Flirts with a nurse. Feeds a stray dog. Goes to a whorehouse. Helps avert a row with the police. Goes to a cabman’s shelter and listens to a sailor tell stories. Breaks into his own house. Urinates under the stars with another man. Watches the sunrise. Kisses his wife on her arse.

It would have been the single busiest, most adventurous day of my life.

From Evan Lavender-Smith’s From Old Notebooks.

Patricide: Patricide is a bad idea, first because it is contrary to law and custom and second because it proves, beyond a doubt, that the father’s every fluted accusation against you was correct: you are a thoroughly bad individual, a patricide! — member of a class of persons universally ill-regarded. It is all right to feel this hot emotion, but not to act upon it. And it is not necessary. It is not necessary to slay your father, time will slay him, that is a virtual certainty. Your true task lies elsewhere. Your true task, as a son, is to reproduce every one of the enormities touched upon in this manual, but in attenuated form. You must become your father, but a paler, weaker version of him. The enormities go with the job, but close study will allow you to perform the job less well than it has previously been done, thus moving toward a golden age of decency, quiet, and calmed fevers. Your contribution will not be a small one, but “small” is one of the concepts that you should shoot for. If your father was a captain in Battery D, then content yourself with a corporalship in the same battery. Do not attend the annual reunions. Do not drink beer or sing songs at the reunions. Begin by whispering, in front of a mirror, for thirty minutes a day. Then tie your hands behind your back for thirty minutes a day, or get someone else to do this for you. Then, choose one of your most deeply held beliefs, such as the belief that your honors and awards have something to do with you, and abjure it. Friends will help you abjure it, and can be telephoned if you begin to backslide. You see the pattern, put it into practice. Fatherhood can be, if not conquered, at least “turned down” in this generation — by the combined efforts of all of us together.

From Donald Barthelme’s novel The Dead Father.

You have too many white walls. More colour is wanted. You should have such men as Whistler among you to teach you the beauty and joy of colour. Take Mr. Whistler’s ‘Symphony in White,’ which you no doubt have imagined to be something quite bizarre. It is nothing of the sort. Think of a cool grey sky flecked here and there with white clouds, a grey ocean and three wonderfully beautiful figures robed in white, leaning over the water and dropping white flowers from their fingers. Here is no extensive intellectual scheme to trouble you, and no metaphysics of which we have had quite enough in art. But if the simple and unaided colour strike the right key-note, the whole conception is made clear. I regard Mr. Whistler’s famous Peacock Room as the finest thing in colour and art decoration which the world has known since Correggio painted that wonderful room in Italy where the little children are dancing on the walls. Mr. Whistler finished another room just before I came away—a breakfast room in blue and yellow. The ceiling was a light blue, the cabinet-work and the furniture were of a yellow wood, the curtains at the windows were white and worked in yellow, and when the table was set for breakfast with dainty blue china nothing can be conceived at once so simple and so joyous.

The fault which I have observed in most of your rooms is that there is apparent no definite scheme of colour. Everything is not attuned to a key-note as it should be. The apartments are crowded with pretty things which have no relation to one another. Again, your artists must decorate what is more simply useful. In your art schools I found no attempt to decorate such things as the vessels for water. I know of nothing uglier than the ordinary jug or pitcher. A museum could be filled with the different kinds of water vessels which are used in hot countries. Yet we continue to submit to the depressing jug with the handle all on one side. I do not see the wisdom of decorating dinner-plates with sunsets and soup-plates with moonlight scenes. I do not think it adds anything to the pleasure of the canvas-back duck to take it out of such glories. Besides, we do not want a soup-plate whose bottom seems to vanish in the distance. One feels neither safe nor comfortable under such conditions. In fact, I did not find in the art schools of the country that the difference was explained between decorative and imaginative art.

From “House Decoration,” a lecture delivered by Oscar Wilde on his 1882 American tour.

This roving humour (though not with like success) I have ever had, and like a ranging spaniel, that barks at every bird he sees, leaving his game, I have followed all, saving that which I should, and may justly complain, and truly, qui ubique est, nusquam est, which Gesner did in modesty, that I have read many books, but to little purpose, for want of good method; I have confusedly tumbled over divers authors in our libraries, with small profit, for want of art, order, memory, judgment. I never travelled but in map or card, in which mine unconfined thoughts have freely expatiated, as having ever been especially delighted with the study of Cosmography. Saturn was lord of my geniture, culminating, &c., and Mars principal significator of manners, in partile conjunction with my ascendant; both fortunate in their houses, &c. I am not poor, I am not rich; nihil est, nihil deest, I have little, I want nothing: all my treasure is in Minerva’s tower. Greater preferment as I could never get, so am I not in debt for it, I have a competence (laus Deo) from my noble and munificent patrons, though I live still a collegiate student, as Democritus in his garden, and lead a monastic life, ipse mihi theatrum, sequestered from those tumults and troubles of the world, Et tanquam in specula positus, (as he said) in some high place above you all, like Stoicus Sapiens, omnia saecula, praeterita presentiaque videns, uno velut intuitu, I hear and see what is done abroad, how others run, ride, turmoil, and macerate themselves in court and country, far from those wrangling lawsuits, aulia vanitatem, fori ambitionem, ridere mecum soleo: I laugh at all, only secure, lest my suit go amiss, my ships perish, corn and cattle miscarry, trade decay, I have no wife nor children good or bad to provide for. A mere spectator of other men’s fortunes and adventures, and how they act their parts, which methinks are diversely presented unto me, as from a common theatre or scene. I hear new news every day, and those ordinary rumours of war, plagues, fires, inundations, thefts, murders, massacres, meteors, comets, spectrums, prodigies, apparitions, of towns taken, cities besieged in France, Germany, Turkey, Persia, Poland, &c., daily musters and preparations, and such like, which these tempestuous times afford, battles fought, so many men slain, monomachies, shipwrecks, piracies and sea-fights; peace, leagues, stratagems, and fresh alarms. A vast confusion of vows, wishes, actions, edicts, petitions, lawsuits, pleas, laws, proclamations, complaints, grievances are daily brought to our ears. New books every day, pamphlets, corantoes, stories, whole catalogues of volumes of all sorts, new paradoxes, opinions, schisms, heresies, controversies in philosophy, religion, &c. Now come tidings of weddings, maskings, mummeries, entertainments, jubilees, embassies, tilts and tournaments, trophies, triumphs, revels, sports, plays: then again, as in a new shifted scene, treasons, cheating tricks, robberies, enormous villainies in all kinds, funerals, burials, deaths of princes, new discoveries, expeditions, now comical, then tragical matters. Today we hear of new lords and officers created, tomorrow of some great men deposed, and then again of fresh honours conferred; one is let loose, another imprisoned; one purchaseth, another breaketh: he thrives, his neighbour turns bankrupt; now plenty, then again dearth and famine; one runs, another rides, wrangles, laughs, weeps, &c. This I daily hear, and such like, both private and public news, amidst the gallantry and misery of the world; jollity, pride, perplexities and cares, simplicity and villainy; subtlety, knavery, candour and integrity, mutually mixed and offering themselves; I rub on privus privatus; as I have still lived, so I now continue, statu quo prius, left to a solitary life, and mine own domestic discontents: saving that sometimes, ne quid mentiar, as Diogenes went into the city, and Democritus to the haven to see fashions, I did for my recreation now and then walk abroad, look into the world, and could not choose but make some little observation, non tam sagax observator ac simplex recitator, not as they did, to scoff or laugh at all, but with a mixed passion.

From Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy.

Hope is the result of confusing the desire that something should take place with the probability that it will. Perhaps no man is free from this folly of the heart, which deranges the intellect’s correct appreciation of probability to such an extent that, if the chances are a thousand to one against it, yet the event is thought a likely one. Still in spite of this, a sudden misfortune is like a death stroke, whilst a hope that is always disappointed and still never dies, is like death by prolonged torture.

He who has lost all hope has also lost all fear; this is the meaning of the expression “desperate.” It is natural to a man to believe what he wishes to be true, and to believe it because he wishes it, If this characteristic of our nature, at once beneficial and assuaging, is rooted out by many hard blows of fate, and a man comes, conversely, to a condition in which he believes a thing must happen because he does not wish it, and what he wishes to happen can never be, just because he wishes it, this is in reality the state described as “desperation.”

From Arthur Schopenhauer’s “Psychological Observations.” Translated by T. Bailey Saunders.

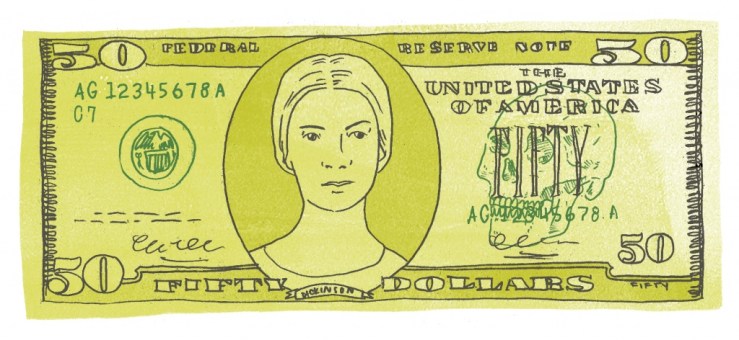

See more American literary icons on American money by Shannon May.

And, by the bye—

In his last novel The Last Novel, David Markson lamented a lack of—

America’s Emily Dickinson dime?

—this preceded by:

Before the Euro, the portrait of Yeats on Ireland’s twenty-pound note.

America’s Whitman twenty-dollar bill, when?

The Melville ten?