It is rather an interesting tale, said the Dead Father, which I shall now tell. I had been fetched by the look of a certain maiden, a raven-haired maiden —He looked at Julie, whose hand strayed to her dark dark hair.

A raven-haired maiden of great beauty. Her name was Tulla. I sent her many presents. Little machines, mostly, a machine for stamping her name on strips of plastic, a machine for extracting staples from documents, a machine for shortening her fingernails, a machine for removing wrinkles from fabric with the aid of steam. Well, she accepted the presents, no difficulty there, but me she spurned. Now as you might imagine I am not fond of being spurned. I am not used to it. In my domains it does not happen but as ill luck would have it she lived just over the county line. Spurned is not a thing I like to be. In fact I have a positive disinclination for it. So I turned myself into a haircut —A haircutter? asked Julie. A haircut, said the Dead Father. I turned myself into a haircut and positioned myself upon the head of a member of my retinue, quite a handsome young man, younger than I, younger than I and stupider, that goes without saying, still not without a certain rude charm, bald as a bladder of lard, though, and as a consequence somewhat diffident in the presence of ladies. Using the long flowing sideburns as one would use one’s knees in guiding a horse —The horseman is still following us, Thomas noted. I wonder why.

— I sent him cantering off in the direction of the delectable Tulla, the Dead Father went on. So superior was the haircut, that is to say, me, joined together with his bumbly youngness, for which I do not blame him, that she succumbed immediately. Picture it. The first night. The touch nonesuch. At the crux I turned myself back into myself (vanishing the varlet) and we two she and I looked at each other and were content. We spent many nights together all roaratorious and filled with furious joy. I fathered upon her in those nights the poker chip, the cash register, the juice extractor, the kazoo, the rubber pretzel, the cuckoo clock, the key chain, the dime bank, the pantograph, the bubble pipe, the punching bag both light and heavy, the inkblot, the nose drop, the midget Bible, the slot-machine slug, and many other useful and humane cultural artifacts, as well as some thousands of children of the ordinary sort. I fathered as well upon her various institutions useful and humane such as the credit union, the dog pound, and parapsychology. I fathered as well various realms and territories all superior in terrain, climatology, laws and customs to this one. I overdid it but I was madly, madly in love, that is all I can say in my own defense. It was a very creative period but my darling, having mothered all this abundance uncomplainingly and without reproach, at last died of it. In my arms of course. Her last words were “enough is enough, Pappy.” I was inconsolable and, driven as if by a demon, descended into the underworld seeking to reclaim her.

I found her there, said the Dead Father, after many adventures too boring to recount. I found her there but she refused to return with me because she had already tasted the food-of-hell and grown fond of it, it’s addicting. She was watched over by eight thunders who hovered over her and brought her every eve ever more hellish delicacies, and watched over furthermore by the ugly-men-of-hell who attacked me with dreampuffs and lyreballs and sought to drive me off. But I removed my garments and threw them at the ugly-men-of-hell, garment by garment, and as each garment touched even ever-so-slightly an ugly-man-of-hell he shriveled into a gasp of steam. There was no way I could stay, there was nothing to stay for; she was theirs.

Then to purify myself, said the Dead Father, of the impurities which had seeped into me in the underworld I dived headfirst into the underground river Jelly, I washed my left eye therein and fathered the deity Poolus who governs the progress of the ricochet or what bounces off what and to what effect, and washed my right eye and fathered the deity Ripple who has the governing of the happening of side effects/unpredictable. Then I washed my nose and fathered the deity Gorno who keeps tombs warm inside and the deity Libet who does not know what to do and is thus an inspiration to us all. I was then beset by eight hundred myriads of sorrows and sorrowing away when a worm wriggled up to me as I sat hair-tearing and suggested a game of pool. A way, he said, to forget. We had, I said, no pool table. Well, he said, are you not the Dead Father? I then proceeded to father the Pool Table of Ballambangjang, fashioning the green cloth of it from the contents of an alfalfa field nearby and the legs of it from telephone poles nearby and the dark pockets of it from the mouths of the leftover ugly-men-of-hell whom I bade stand with their mouths open at the appropriate points —”

What was the worm’s name? Thomas asked.

I forget, said the Dead Father. Then, just as we were chalking our cues, the worm and I, Evil himself appeared, he-of-thegreater-magic, terrible in aspect, I don’t want to talk about it, let me say only that I realized instantly that I was on the wrong side of the Styx. However I was not lacking in wit, even in this extremity. Uncoiling my penis, then in the dejected state, I made a long cast across the river, sixty-five meters I would say, where it snagged most conveniently in the cleft of a rock on the farther shore. Thereupon I hauled myself hand-over-hand ‘midst excruciating pain as you can imagine through the raging torrent to the other bank. And with a hurrah! over my shoulder, to show my enemies that I was yet alive and kicking, I was off like a flash into the trees.

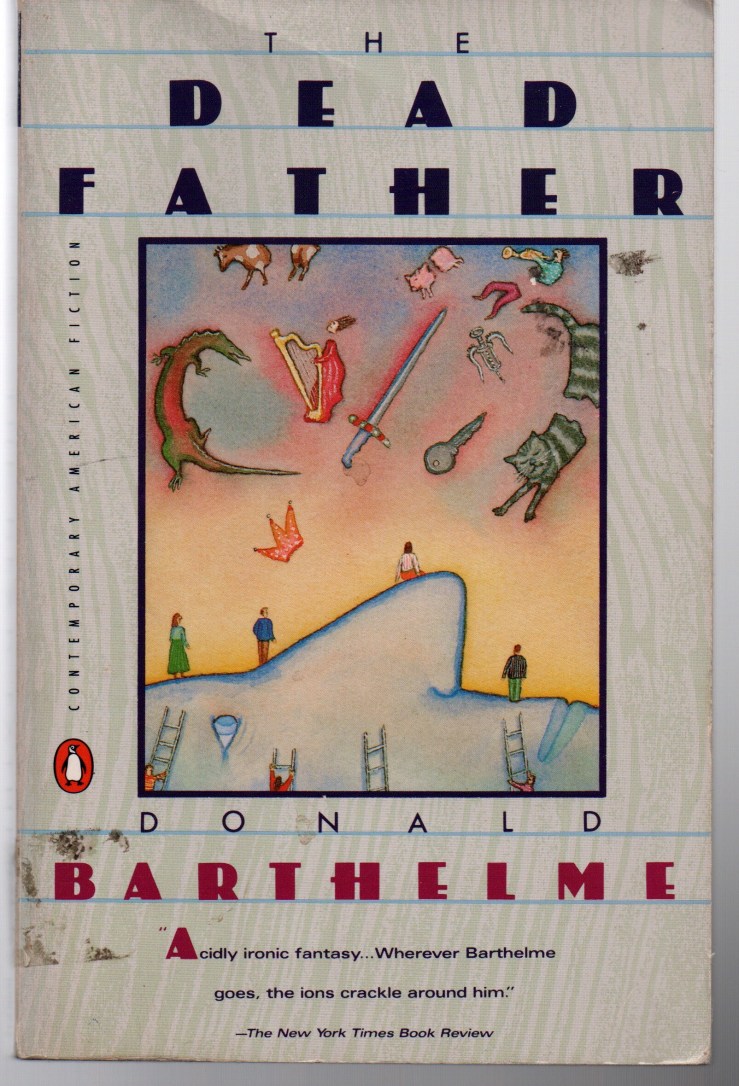

—From Donald Barthelme’s novel The Dead Father.