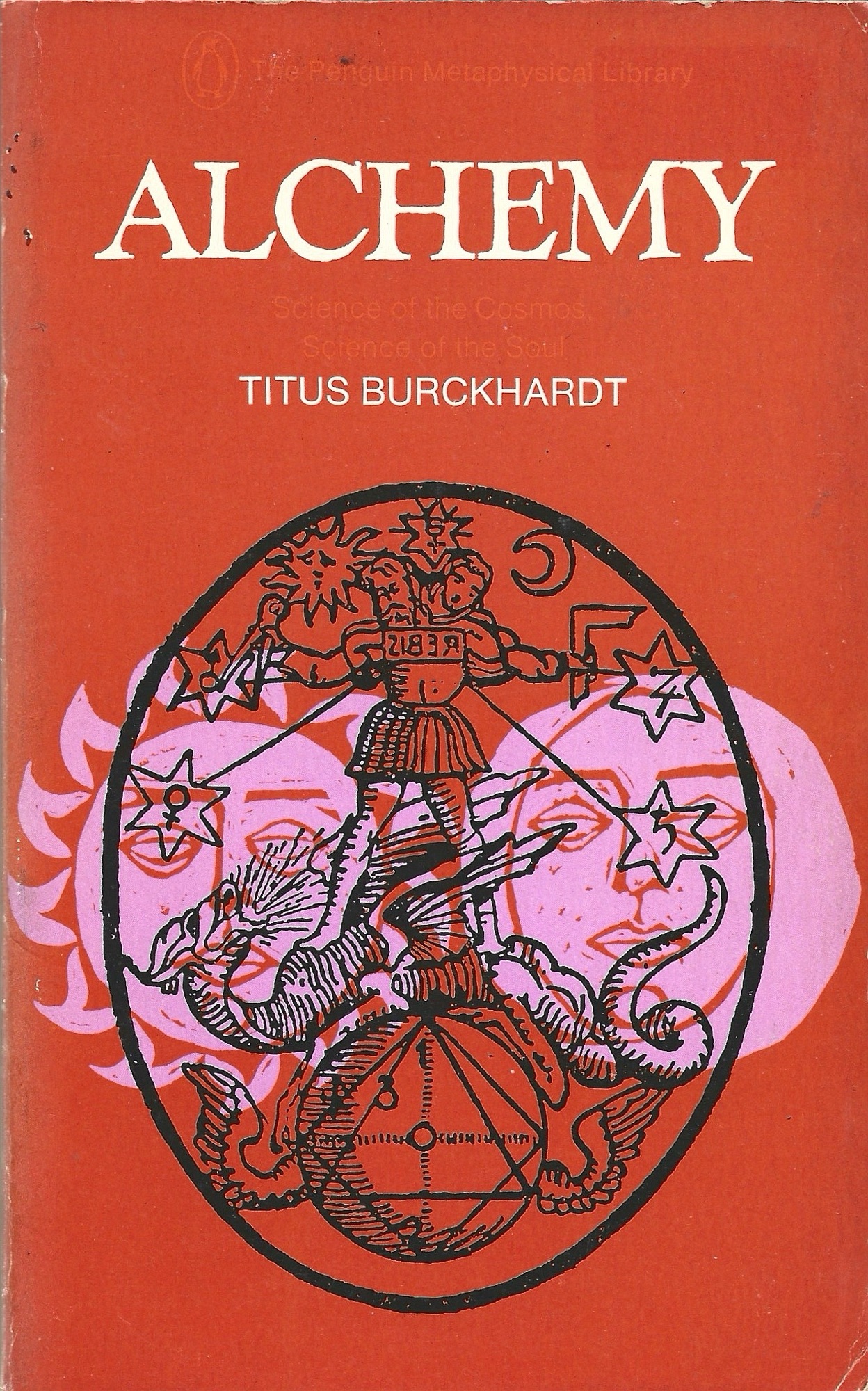

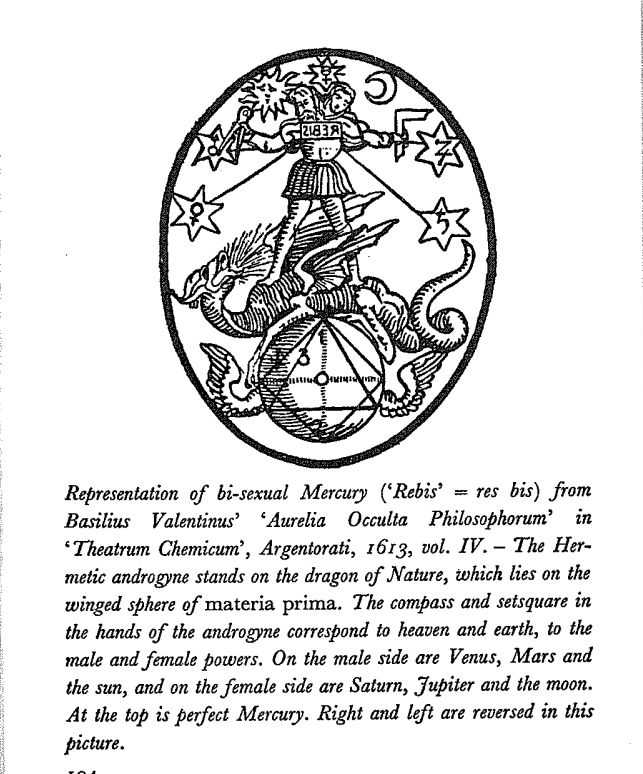

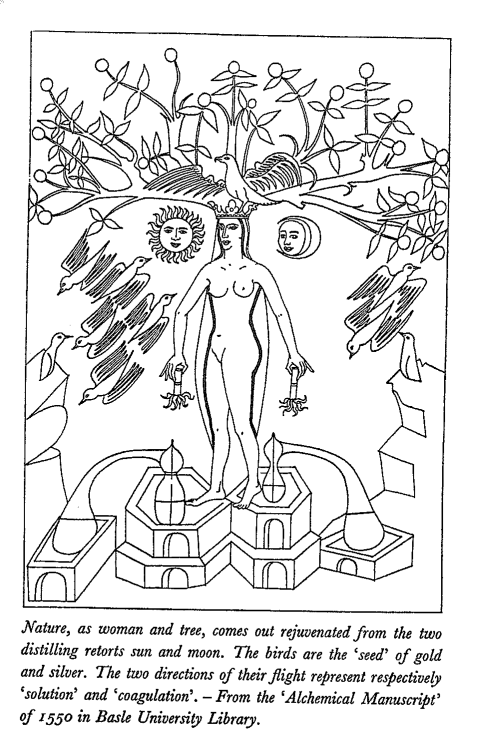

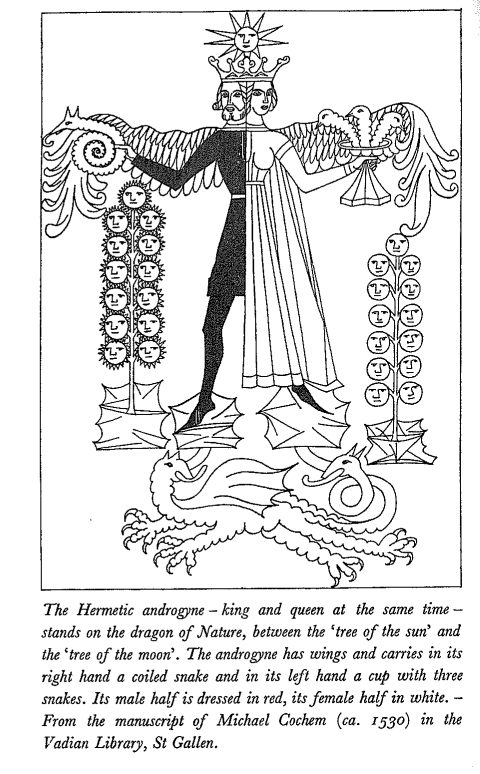

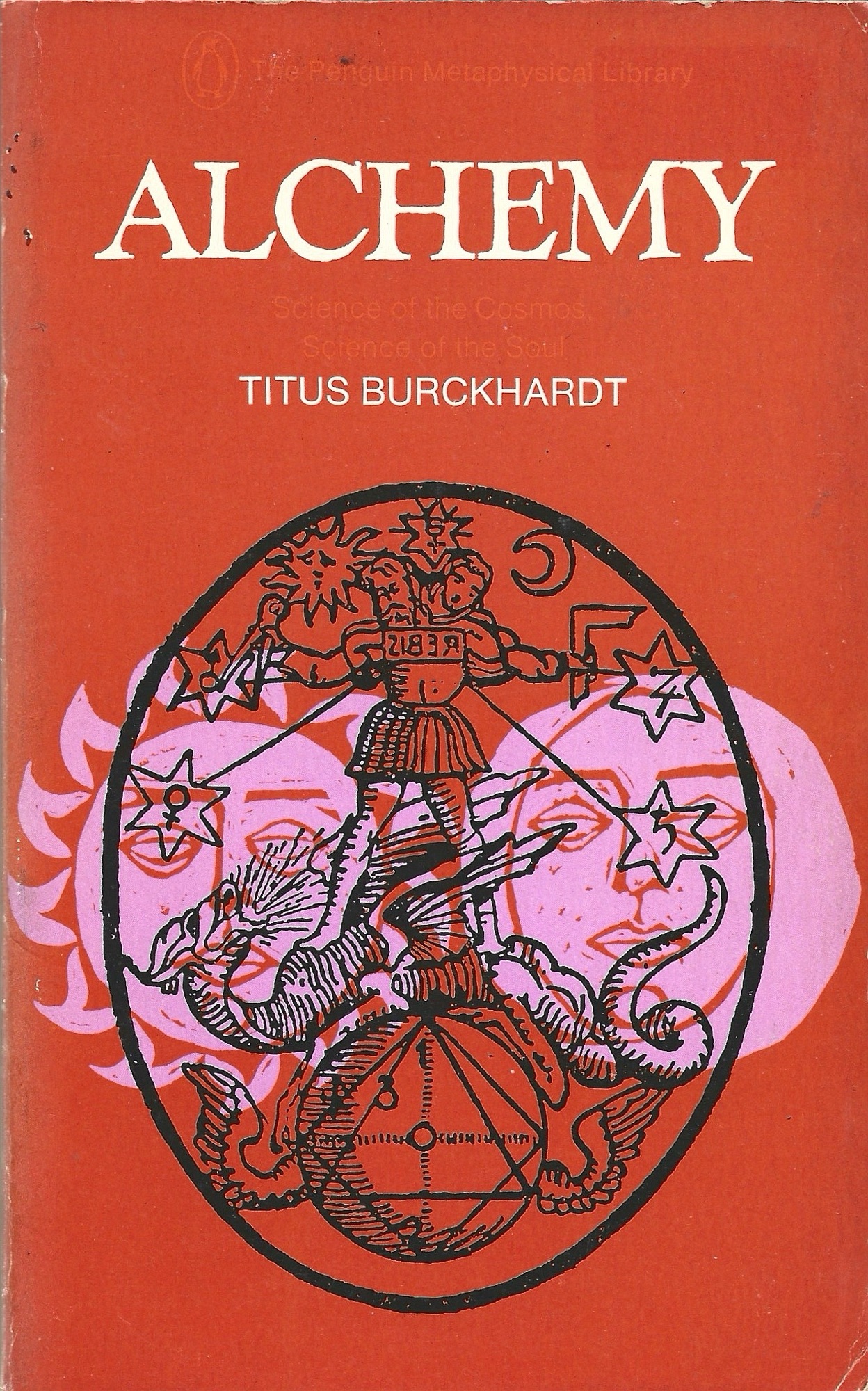

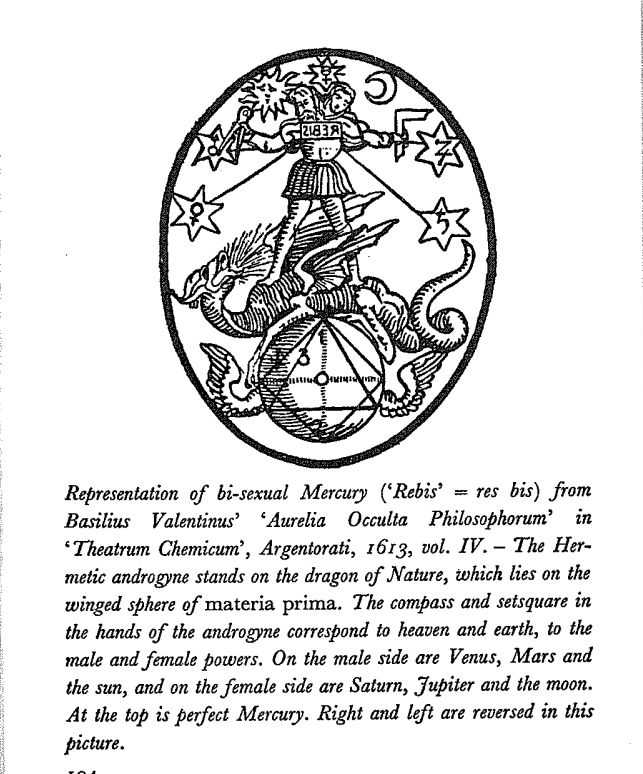

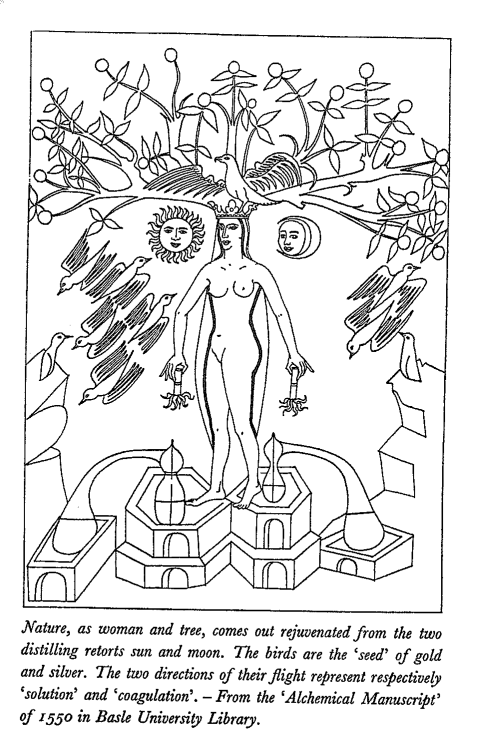

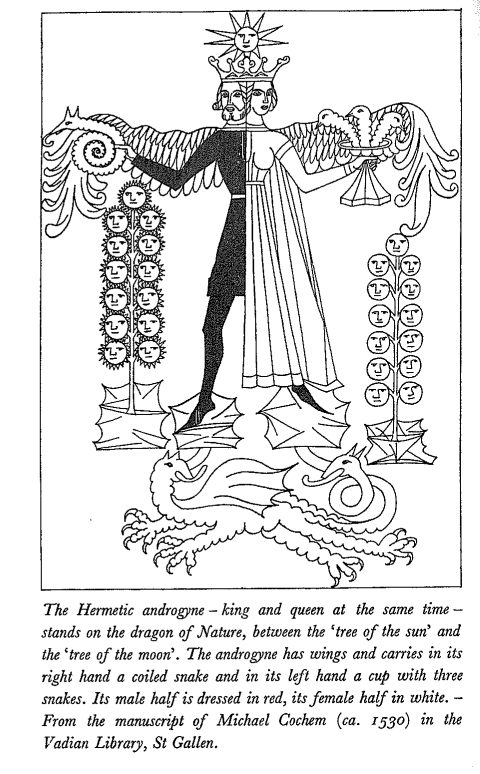

Alchemy, 1960, Titus Burckhardt. Translation by William Stoddart. Penguin Books (1971). Cover design by Walter Brooks employing an illustration from Basilius Valentinus’ Aurelia Occulta Philosophorum. 206 pages.

From Alchemy:

Alchemy, 1960, Titus Burckhardt. Translation by William Stoddart. Penguin Books (1971). Cover design by Walter Brooks employing an illustration from Basilius Valentinus’ Aurelia Occulta Philosophorum. 206 pages.

From Alchemy:

A Dreambook for Our Time, 1963, Tadeusz Konwicki. Translation by David Welsh. Penguin Books (1976). Cover illustration by Christopher Davis; cover design by Walter Brooks. 282 pages.

Stories and Plays, collected 1974, Flann O’Brien. Penguin Books (1977). Cover design by Neil Stuart. 208 pages.

From “A Bash in the Tunnel” —

James Joyce was an artist. He has said so himself. His was a case of Ars gratia Artist. He declared that he would pursue his artistic mission even if the penalty was as long as eternity itself. This seems to be an affirmation of belief in Hell, therefore of belief in Heaven and God.

Hello America, 1981, J.G. Ballard. Triad Grenada (1983). Cover illustration by Tim White. 236 pages.

Today’s mass-market Monday selection was inspired by last night’s rewatch of David Cronenberg’s 1975 film Shivers. Shivers’ first fortyish minutes play as one of the more persuasive Ballardian commitments to film—more Ballardian than Cronenberg’s Crash (2016) or Ben Wheatley’s High-Rise (2015). Indeed, Shivers is an aesthetic foster twin to Ballard’s novel High-Rise, born the same year. High-Rise is far superior to Hello America, but I think Hello America is probably better than it comes off in my short review from 2022:

You’d think a novel where President Manson wants to make America great Again would feel more prescient, but Ballard’s so in love here with the sparkle and pop of Pop Art America that he fails to attend to the dirt, grease, and grime that make the machine run. A fun novel, but its contemporary currency is squashed not so much by historical reality as the weight of Ballard’s oeuvre before it.

The Doors of Perception, 1955, Aldous Huxley. Perennial Library (1970). Cover design by Pat Steir. 79 pages.

Here’s Huxley on mescaline, marveling at the folds of cloth in Botticelli’s Judith:

Civilized human beings wear clothes, therefore there can be no portraiture, no mythological or historical storytelling without representations of folded textiles. But though it may account for the origins, mere tailoring can never explain the luxuriant development of drapery as a major theme of all the plastic arts. Artists, it is obvious, have always loved drapery for its own sake – or, rather, for their own. When you paint or carve drapery, you are painting or carving forms which, for all practical purposes, are nonrepresentational-the kind of unconditioned forms on which artists even in the most naturalistic tradition like to let themselves go. In the average Madonna or Apostle the strictly human, fully representational element accounts for about ten per cent of the whole. All the rest consists of many colored variations on the inexhaustible theme of crumpled wool or linen. And these non-representational nine-tenths of a Madonna or an Apostle may be just as important qualitatively as they are in quantity. Very often they set the tone of the whole work of art, they state the key in which the theme is being rendered, they express the mood, the temperament, the attitude to life of the artist. Stoical serenity reveals itself in the smooth surfaces, the broad untortured folds of Piero’s draperies. Torn between fact and wish, between cynicism and idealism, Bernini tempers the all but caricatural verisimilitude of his faces with enormous sartorial abstractions, which are the embodiment, in stone or bronze, of the everlasting commonplaces of rhetoric – the heroism, the holiness, the sublimity to which mankind perpetually aspires, for the most part in vain. And here are El Greco’s disquietingly visceral skirts and mantles; here are the sharp, twisting, flame-like folds in which Cosimo Tura clothes his figures: in the first, traditional spirituality breaks down into a nameless physiological yearning; in the second, there writhes an agonized sense of the world’s essential strangeness and hostility. Or consider Watteau; his men and women play lutes, get ready for balls and harlequinades, embark, on velvet lawns and under noble trees, for the Cythera of every lover’s dream; their enormous melancholy and the flayed, excruciating sensibility of their creator find expression, not in the actions recorded, not in the gestures and the faces portrayed, but in the relief and texture of their taffeta skirts, their satin capes and doublets. Not an inch of smooth surface here, not a moment of peace or confidence, only a silken wilderness of countless tiny pleats and wrinkles, with an incessant modulation – inner uncertainty rendered with the perfect assurance of a master hand – of tone into tone, of one indeterminate color into another. In life, man proposes, God disposes. In the plastic arts the proposing is done by the subject matter; that which disposes is ultimately the artist’s temperament, proximately (at least in portraiture, history and genre) the carved or painted drapery. Between them, these two may decree that a fete galante shall move to tears, that a crucifixion shall be serene to the point of cheerfulness, that a stigmatization shall be almost intolerably sexy, that the likeness of a prodigy of female brainlessness (I am thinking now of Ingres’ incomparable Mme. Moitessier) shall express the austerest, the most uncompromising intellectuality.

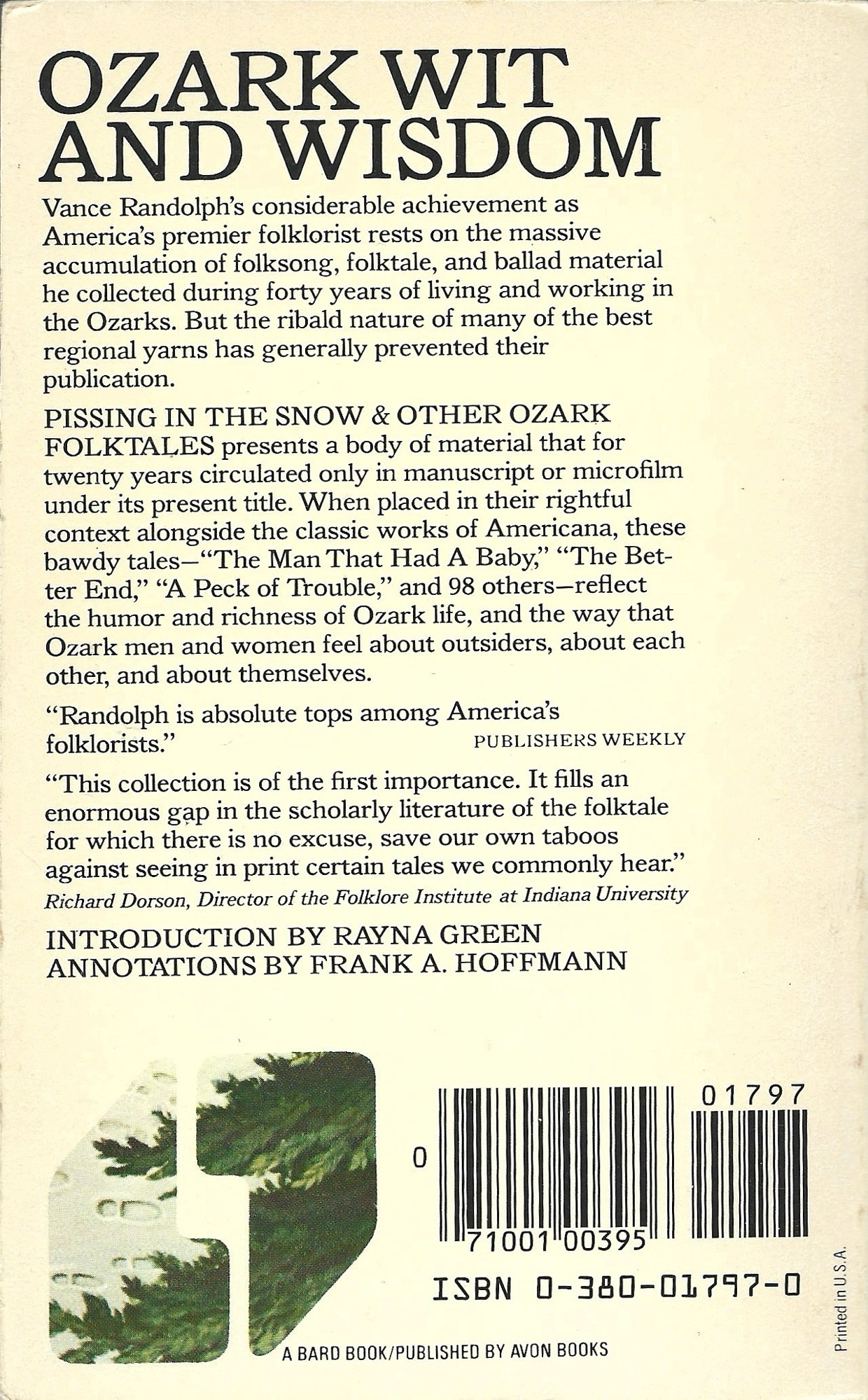

Pissing in the Snow & Other Ozark Folktales, collected and transcribed by Vance Randolph with annotations by Frank A. Hoffmann. Avon Bard (1977). No cover artist credited. 239 pages. A tale from the collection:

“Have You Ever Been Diddled?”

Told by J. L. Russell, Harrison, Ark., April, 1950. He heard this one near Berryville, Ark., in the 1890’s.

One time there was a town girl and a country girl got to talking about the boys they had went with. The town girl told what kind of a car her boyfriends used to drive, and how much money their folks has got. But the country girl didn’t take no interest in things like that, and she says the fellows are always trying to get into her pants.

So finally the town girl says, “Have you ever been diddled?” The country girl giggled, and she says yes, a little bit.

“How much?” says the town girl. “Oh, about like that,” says the country girl, and she held up her finger to show an inch, or maybe an inch and a half.

The town girl just laughed, and pretty soon the country girl says, “Have you ever been diddled?” The town girl says of course she has, lots of times. “How much?” says the country girl. “Oh, about like that,” says the town girl, and she marked off about eight inches, or maybe nine.

The country girl just set there goggle-eyed, and she drawed a deep breath. “My God,” says the country girl, “that ain’t diddling! Why, you’ve been fucked!”

[J1805.5]

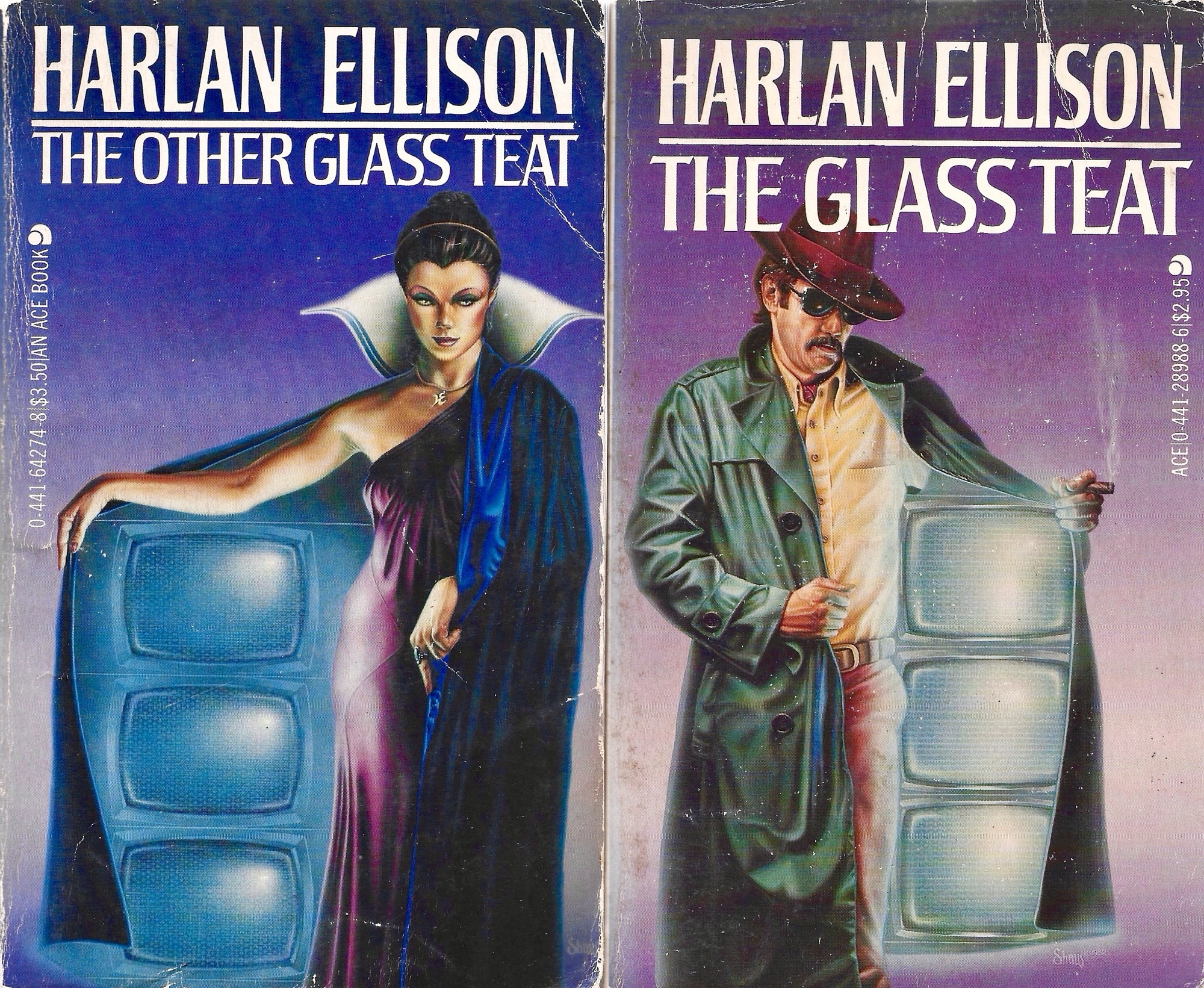

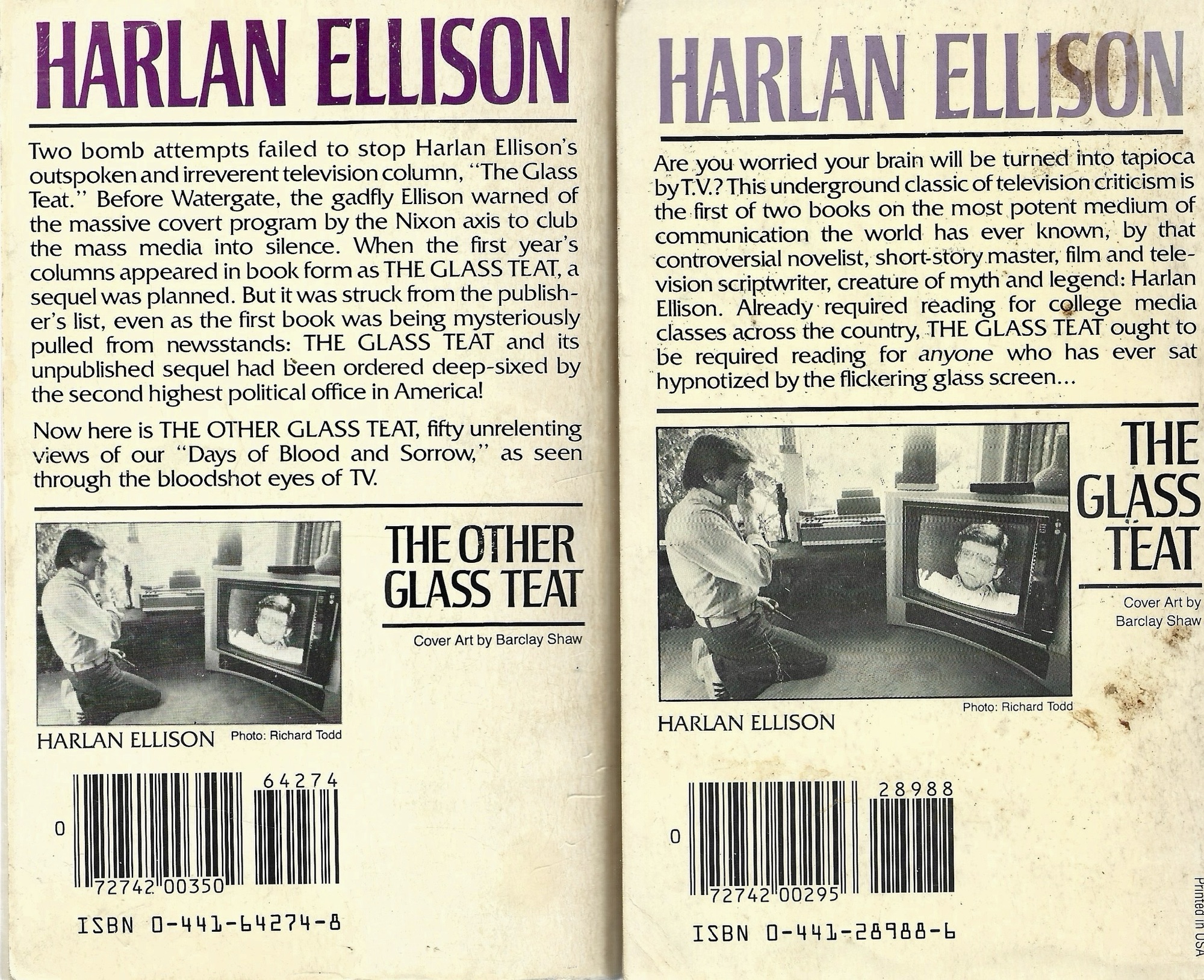

The Glass Teat, Harlan Ellison. Ace Books (1983 reprint). Cover art by Barclay Shaw. 319 pages.

The Other Glass Teat, Harlan Ellison. Ace Books (1983). Cover art by Barclay Shaw. 397 pages.

Part of an ostensible review of the sitcom Happy Days; from Ellison’s column published on 3 July 1970 and reprinted in The Other Glass Teat:

One begins to realize that our national middle-class hunger to return to two decades of Depression, world war, Prohibition, Racism Unadmitted, Covert Fascination with Sex, Deadly Innocence, Isolationism, Provincialism, and Deprivation Remembered as Good Old Days has become a cultural sickness.

The past has always been a rich source for fun and profit. Nostalgia is a good thing. It keeps us from forgetting our roots. Readers of this column know I trip down Memory Lane myself frequently. But it is clearly evident that when an entire nation refuses to accept the responsibilities of its own future, when it seeks release in a morbid fascination with its past, and when it elevates the dusty dead days of the past to a pinnacle position of Olympian grandeur … we are in serious trouble.

Neuromancer, William Gibson. Ace Books (1984 imprint; 29th printing). No cover designer or artist credited. 271 pages.

ISFDB gives the cover artist as Rick Berry.

I borrowed and never returned Neuromancer from one of my best friends. We were best friends in middle school, but I stole this book like senior year of high school or maybe the year after. 1997ish, when the world seemed fairly settled.

According to a blog I wrote in 2006 (JFC), I lost my friend’s copy to one of my students, who took it and never returned it. Did I buy this 29th printing to replace the copy that I’d sorta-kinda-stolen years ago? I can’t recall. I vaguely recall doing so, but it’s also possible I’ve fabricated the past, creating memories like a man wielding large shears and bolts of felt might create strange stupid felt shapes.

Tilford, I’m sorry. You probably can’t have your book back, but you can have this one. Just let me know.

I would love to bottle the feeling of reading those first three Gibson novels and to sip from that bottle, but that’s nostalgia, and fuck nostalgia.

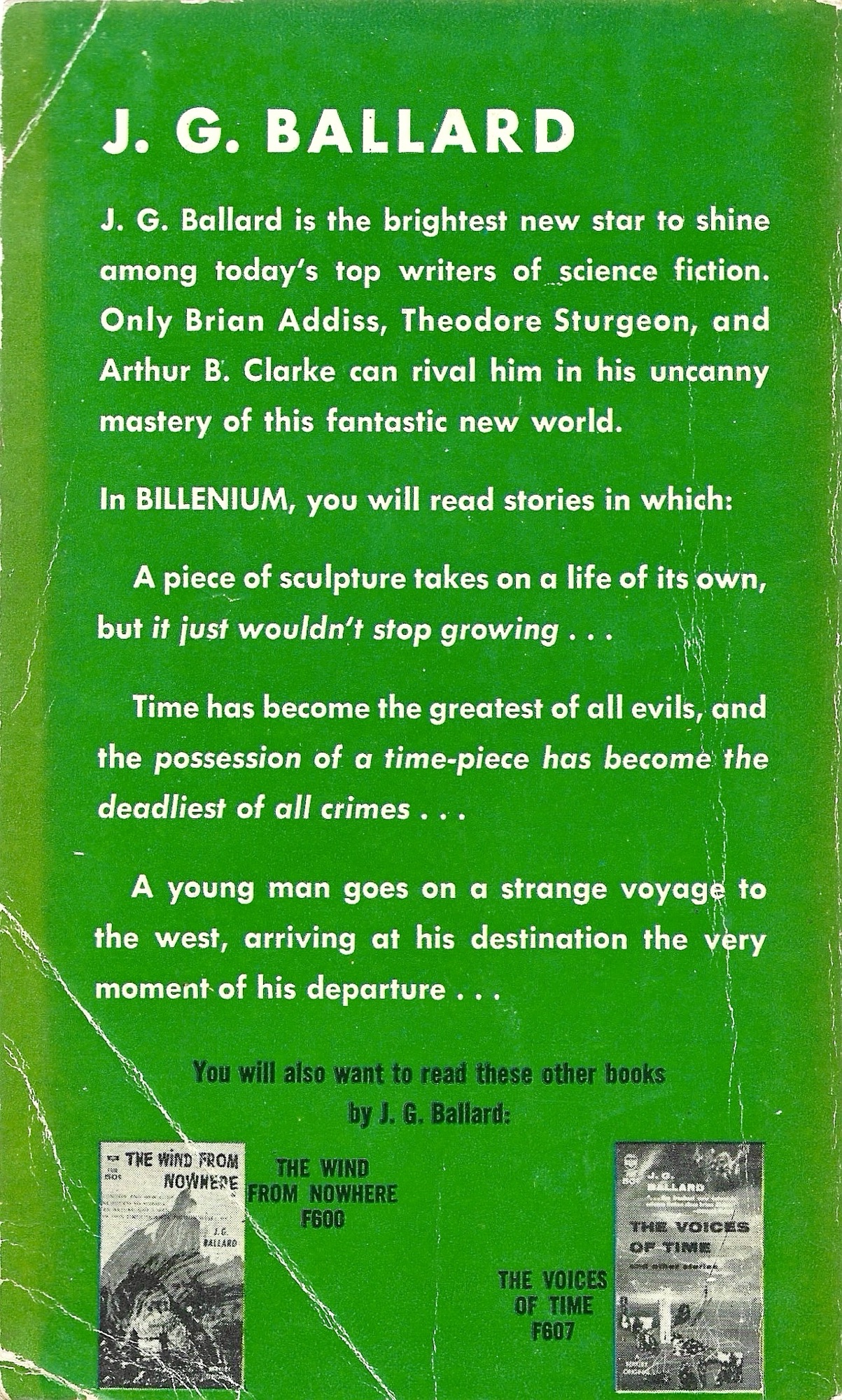

Billenium, J.G. Ballard. Berkley Medallion Books (1962). No cover designer or artist credited. 159 pages.

ISFDB credits Richard Powers as the cover artist.

Ten years ago I read The Complete Short Stories of J.G. Ballard and wrote about them on this blog. At the end of the (exhausting) project (about 1200 pages and just under 100 stories), I made a shortlist of 23 “essential” J.G. Ballard short stories. I included two of the ten stories from Billenium in that list: the title track “Billenium” and “Chronopolis.” Of the latter, I wrote:

“Chronopolis” offers an interesting central shtick: Clocks and other means of measuring and standardizing time have been banned. But this isn’t what makes the story stick. No, Ballard apparently tips his hand early, revealing why measuring time has been banned—it allows management to control labor:

‘Isn’t it obvious? You can time him, know exactly how long it takes him to do something.’ ‘Well?’ ‘Then you can make him do it faster.’

But our intrepid young protagonist (Conrad, his loaded name is), hardly satisfied with this answer, sneaks off to the city of the past, the titular chronopolis, where he works to restore the timepieces of the past. “Chronopolis” depicts a technologically-regressive world that Ballard will explore in greater depth with his novel The Drowned World, but the details here are precise and fascinating (if perhaps ultimately unconvincing if we try to apply them as any kind of diagnosis for our own metered age). Ending on a perfect paranoid note, Ballard borrows just a dab of Poe here, synthesizing his influence into something far more original, far more Ballardian. Let’s include it in something I’m calling The Essential Short Stories of J.G. Ballard.

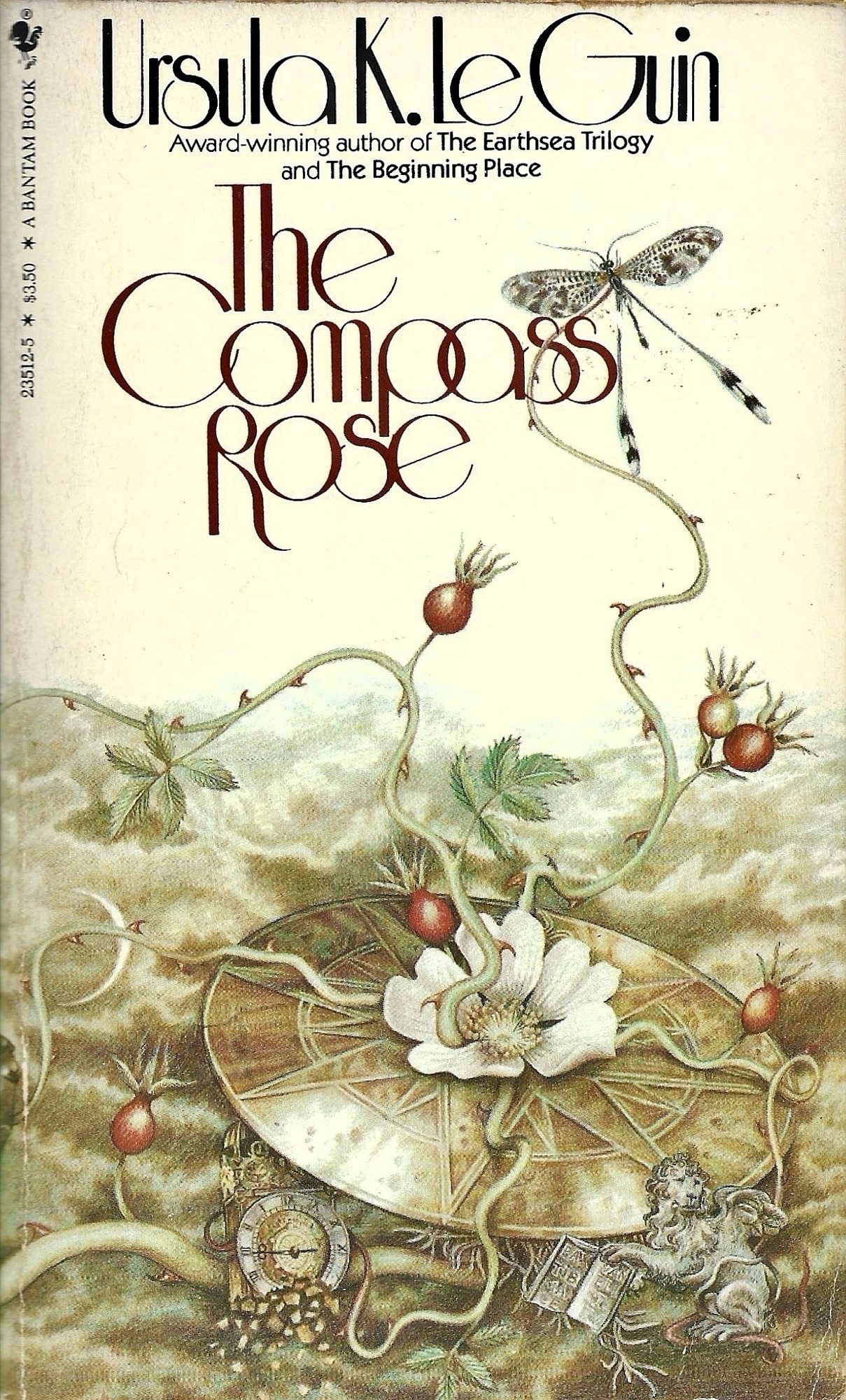

The Compass Rose, Ursula K. Le Guin. Bantam Books (1983). Cover art by Yvonne Gilbert. 271 pages.

A strong collection, containing one of Le Guin’s classic stories, “Schrödinger’s Cat,” which I wrote about a few years ago. From that riff:

Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1982 short story “Schrödinger’s Cat” is a tale about living in radical uncertainty. The story is perhaps one of the finest examples of postmodern literature I’ve ever read. Playful, funny, surreal, philosophical, and a bit terrifying, the story is initially frustrating and ultimately rewarding.

While I think “Schrödinger’s Cat” has a thesis that will present itself to anyone who reads it more than just once or twice, the genius of the story is in Le Guin’s rhetorical construction of her central idea. She gives us a story about radical uncertainty by creating radical uncertainty in her reader, who will likely find the story’s trajectory baffling on first reading. Le Guin doesn’t so much eschew as utterly disrupt the traditional form of a short story in “Schrödinger’s Cat”: setting, characters, and plot are all presented in a terribly uncertain way.

The Messenger, Charles Wright. Manor Books (1974). No cover artist or designer credited. 217 pages.

Charles Wright (not to be confused with Charles Wright or Charles Wright) published three novels between 1963 and 1973. His second novel, The Wig (1966) is an under-read, underappreciated gem—a tragicomic satire employing sharp distortions and cartoony edges. Wright’s first novel, The Messenger, is perhaps a bit too beholden to Richard Wright (to whom it is dedicated (along with Billie Holiday))—but many readers may prefer its raw realism to The Wig’s zany (and often crushing) zigs and zags. His last published novel, Absolutely Nothing to Get Alarmed About, is the most accomplished and singular of the trio—fragmentary, polyglossic, kaleidoscopic, messy. The trio remains in print as an omnibus with an introduction by Ishmael Reed. Read Reed on reading Wright.

The Colossus of Maroussi, Henry Miller. Penguin Books (1964). Cover Osbert Lancaster. 248 pages.

From Miller’s The Colossus of Maroussi (1941):

At Arachova Ghika got out to vomit. I stood at the edge of a deep canyon and as I looked down into its depths I saw the shadow of a great eagle wheeling over the void. We were on the very ridge of the mountains, in the midst of a convulsed land which was seemingly still writhing and twisting. The village itself had the bleak, frostbitten look of a community cut off from the outside world by an avalanche. There was the continuous roar of an icy waterfall which, though hidden from the eye, seemed omnipresent. The proximity of the eagles, their shadows mysteriously darkening the ground, added to the chill, bleak sense of desolation. And yet from Arachova to the outer precincts of Delphi the earth presents one continuously sublime, dramatic spectacle. Imagine a bubbling cauldron into which a fearless band of men descend to spread a magic carpet. Imagine this carpet to be composed of the most ingenious patterns and the most variegated hues. Imagine that men have been at this task for several thousand years and that to relax for but a season is to destroy the work of centuries. Imagine that with every groan, sneeze or hiccough which the earth vents the carpet is grievously ripped and tattered. Imagine that the tints and hues which compose this dancing carpet of earth rival in splendor and subtlety the most beautiful stained glass windows of the mediaeval cathedrals. Imagine all this and you have only a glimmering comprehension of a spectacle which is changing hourly, monthly, yearly, millennially. Finally, in a state of dazed, drunken, battered stupefaction you come upon Delphi. It is four in the afternoon, say, and a mist blowing in from the sea has turned the world completely upside down. You are in Mongolia and the faint tinkle of bells from across the gully tells you that a caravan is approaching. The sea has become a mountain lake poised high above the mountaintops where the sun is sputtering out like a rum-soaked omelette. On the fierce glacial wall where the mist lifts for a moment someone has written with lightning speed in an unknown script. To the other side, as if borne along like a cataract, a sea of grass slips over the precipitous slope of a cliff. It has the brilliance of the vernal equinox, a green which grows between the stars in the twinkling of an eye.

Seeing it in this strange twilight mist Delphi seemed even more sublime and awe-inspiring than I had imagined it to be. I actually felt relieved, upon rolling up to the little bluff above the pavilion where we left the car, to find a group of idle village boys shooting dice: it gave a human touch to the scene. From the towering windows of the pavilion, which was built along the solid, generous lines of a mediaeval fortress, I could look across the gulch and, as the mist lifted, a pocket of the sea became visible—just beyond the hidden port of Itea. As soon as we had installed our things we looked for Katsimbalis whom we found at the Apollo Hotel—I believe he was the only guest since the departure of H. G. Wells under whose name I signed my own in the register though I was not stopping at the hotel. He, Wells, had a very fine, small hand, almost womanly, like that of a very modest, unobtrusive person, but then that is so characteristic of English handwriting that there is nothing unusual about it.

By dinnertime it was raining and we decided to eat in a little restaurant by the roadside. The place was as chill as the grave. We had a scanty meal supplemented by liberal portions of wine and cognac. I enjoyed that meal immensely, perhaps because I was in the mood to talk. As so oft en happens, when one has come at last to an impressive spot, the conversation had absolutely nothing to do with the scene. I remember vaguely the expression of astonishment on Ghika’s and Katsimbalis’ faces as I unlimbered at length upon the American scene. I believe it was a description of Kansas that I was giving them; at any rate it was a picture of emptiness and monotony such as to stagger them. When we got back to the bluff behind the pavilion, whence we had to pick our way in the dark, a gale was blowing and the rain was coming down in bucketfuls. It was only a short stretch we had to traverse but it was perilous. Being somewhat lit up I had supreme confidence in my ability to find my way unaided. Now and then a flash of lightning lit up the path which was swimming in mud. In these lurid moments the scene was so harrowingly desolate that I felt as if we were enacting a scene from Macbeth. “Blow wind and crack!” I shouted, gay as a mud-lark, and at that moment I slipped to my knees and would have rolled down a gully had not Katsimbalis caught me by the arm. When I saw the spot next morning I almost fainted.

The Belan Deck, Matt Bucher. SSMG Press (2023; second printing). Cover design by David Jensen. 119 pages.

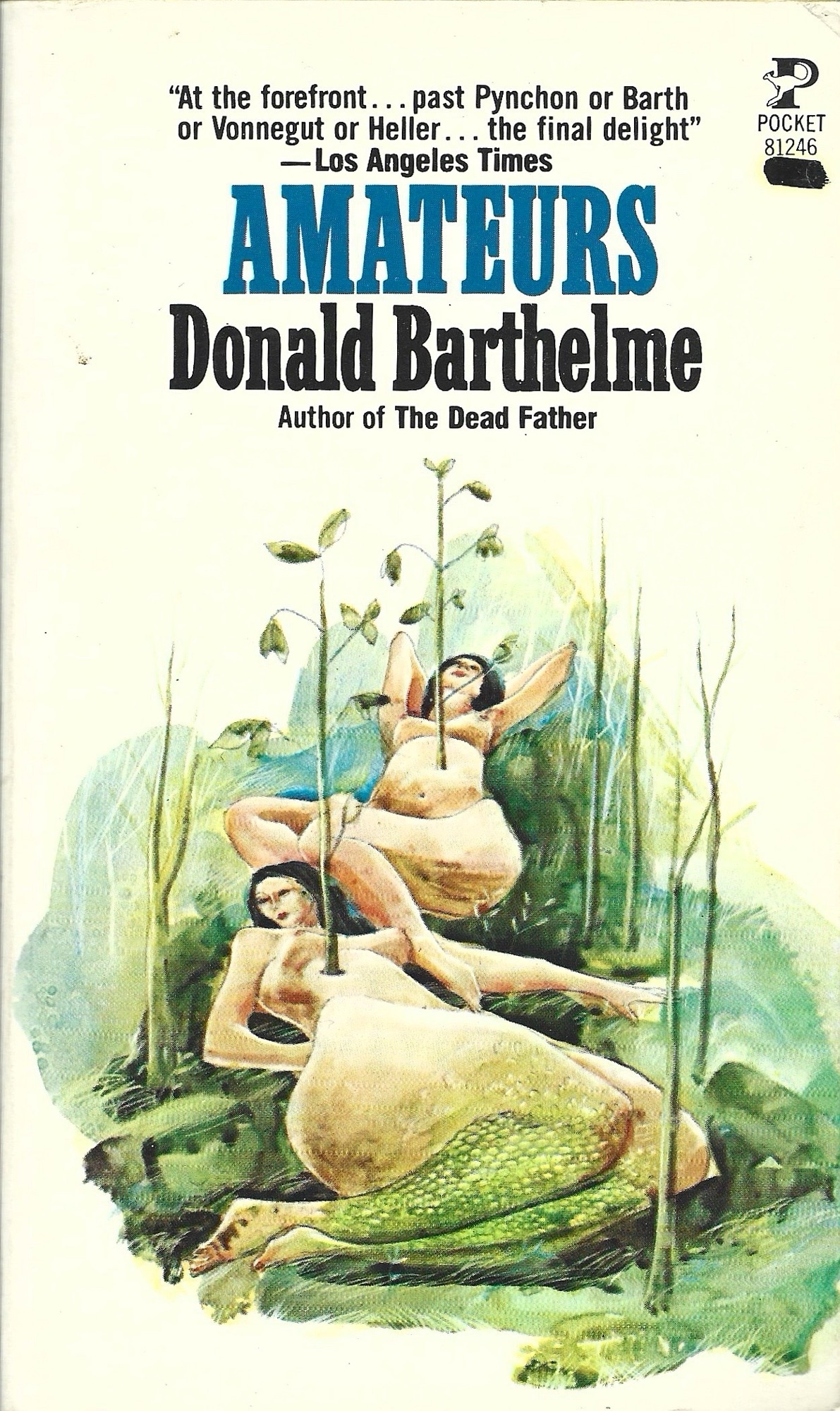

Amateurs, Donald Barthelme. Kangaroo Pocket Books (1977). No cover artist or designer credited. 207 pages.

I’ve written a few times about my slow acquisition of someone else’s library. This person lives in Perry, Florida, a small panhandle town south of Tallahassee, and I guess he drives into Jacksonville at least once a year to sell books at the bookstore I frequent. I’ve talked to the bookstore’s owner about him a few times. Sometimes, I’ll spot a spine and think, Yeah, his name and address are going to be stamped on the inside cover. And there it was this Friday when I picked up his mass-market edition of Amateurs. His by-now familiar habit of checking off volumes by the same author is on display here too. He also put neat pencil dashes by some of the stories in Amateurs, including my favorite from the collection, “Some of Us Had Been Threatening Our Friend Colby.” He also checked off “The Educational Experience,” which, in this Kangaroo edition of Amateurs, sadly fails to include Barthelme’s collage illustrations that accompanied the piece when it first ran in Harper’s

Continue reading “Mass-Market Monday | Donald Barthelme’s Amateurs”

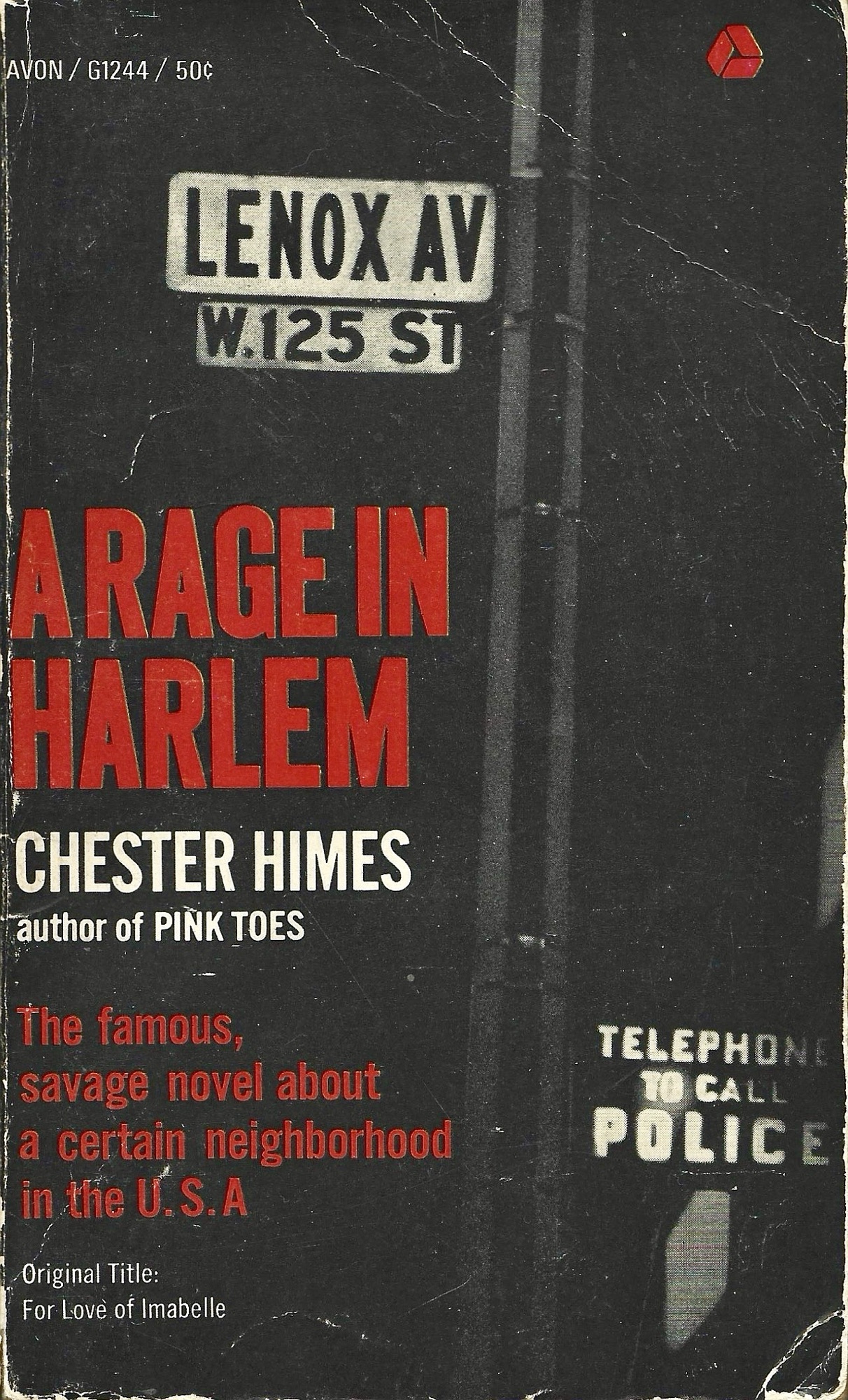

A Rage in Harlem, Chester Himes. Avon Books (1965). No cover artist or designer credited. 192 pages.

Himes’ A Rage in Harlem is a quick, mean, sharp read. I came to Himes via Ishmael Reed, who wrote of the author in a 1991 LA Times review of Himes’ Collected Stories,

James Baldwin, another proud and temperamental genius, said that if he hadn’t left the United States he would have killed someone. The same could be said of Chester Himes, the intellectual and gangster who left the United States for Europe in the 1950s. He achieved fame abroad with his Harlem detective series, which are remarkable for their macabre comic sense and wicked and nasty wit so brilliantly captured in Bill Duke’s A Rage in Harlem.

Three Trapped Tigers, G. Cabrera Infante. Translated by Donald Gardner and Suzanne Jill Levine with Guillermo Cabrera Infante. Avon Bard (1985). No cover artist or designer credited. 473 pages.

A busy buzzy book honking and howling and hooting, I am loving loving loving Three Trapped Tigers—it sings and shouts and hollers. The novel starts with a polyglossic emcee announcing the parade of honorable horribles who will strut through the novel (if it is indeed a “novel”). Very funny, very engrossing, grand stuff, love it.

Here’s Salman Rushdie, reviewing the novel in the LRB back in 1981 (he’s just fumbled around answering “What is this crazy book actually about?”:

So much for the plot. (Warning: this review is about to go out of control.) What actually matters in Three Trapped Tigers is words, language, literature, words. Take the title. Originally, in the Cuban, they were three sad tigers, Tres tristes tigres, the beginning of a tongue-twister. For Cabrera, phonetics always come before meaning (correction: meaning is to be found in phonetic associations), and so the English title twists the sense in order to continue twisting the tongue. Very right and improper. Then there is the matter of the huge number of other writers whose influence must be acknowledged: Cabrera Infante calls them, reverently, Fuckner and Shame’s Choice. (He is less kind to Stephen Spent and Green Grams, who wrote, as of course you know, Travels with my Cant.) Which brings us to the novel’s most significant character, a sort of genius at torturing language called Bustrofedon, who scarcely appears in the story at all, of whom we first hear when he’s dying, but who largely dominates the thoughts of all the Silvestres and Arsenios and Codacs he leaves behind him. This Bustromaniac (who is keen on the bustrofication of words) gives us the Death of Trotsky as described by seven Cuban writers – a set of parodies whose point is that all the writers described are so pickled in Literature that they can’t take up their pens without trying to wow us with their erudition. Three Trapped Tigers, like Bustrofedon’s whole life, is dedicated to a full frontal assault on the notion of Literature as Art. It gives us nonsense verses, a black page, a page which says nothing but blen blen blen, a page which has to be read in the mirror: Sterne stuff. But it also gives us Bustrolists of ‘words that read differently in the mirror’: Live/evil, drab/bard, Dog/God; and the Confessions of a Cuban Opinion Eater; and How to kill an elephant: aboriginal method ... the reviewer is beginning to cackle hysterically at this point, and has decided to present his opinion in the form of puns, thus: ‘The Havana night may be dark and full of Zorro’s but Joyce cometh in the morning.’ Or: ‘Despite the myriad influences, Cabrera Infante certainly paddles his own Queneau.’