Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1982 short story “Schrödinger’s Cat” is a tale about living in radical uncertainty. The story is perhaps one of the finest examples of postmodern literature I’ve ever read. Playful, funny, surreal, philosophical, and a bit terrifying, the story is initially frustrating and ultimately rewarding.

While I think “Schrödinger’s Cat” has a thesis that will present itself to anyone who reads it more than just once or twice, the genius of the story is in Le Guin’s rhetorical construction of her central idea. She gives us a story about radical uncertainty by creating radical uncertainty in her reader, who will likely find the story’s trajectory baffling on first reading. Le Guin doesn’t so much eschew as utterly disrupt the traditional form of a short story in “Schrödinger’s Cat”: setting, characters, and plot are all presented in a terribly uncertain way.

The opening line points to some sort of setting and problem. Our first-person narrator tells us: “As things appear to be coming to some sort of climax, I have withdrawn to this place.” The vagueness of “things,” “some sort,” and “this place” continues throughout the tale, but are mixed with surreal, impossible, and precise images.

The first characters the narrator introduces us to are a “married couple who were coming apart. She had pretty well gone to pieces, but he seemed, at first glance, quite hearty.” The break up here is literal, not just figurative—this couple is actually falling apart, fragmenting into pieces. (Although the story will ultimately place under great suspicion that adverb actually). Le Guin’s linguistic play points to language’s inherent uncertainty, to the undecidability of its power to fully refer. As the wife’s person falls into a heap of limbs, the husband wryly observes, “My wife had great legs.” Horror mixes with comedy here. The pile of fragmented parts seems to challenge the reader to put the pieces together in some new way. “Well, the couple I was telling you about finally broke up,” our narrator says, and then gives us a horrific image of the pair literally broken up:

The pieces of him trotted around bouncing and cheeping, like little chicks; but she was finally reduced to nothing but a mass of nerves: rather like fine chicken wire, in fact, but hopelessly tangled.

Nothing but a mass of nerves hopelessly tangled: one description of the postmodern condition.

The bundle of tangled nerves serves as something that our narrator must resist, and resistance takes the form of storytelling: “Yet the impulse to narrate remains,” we’re told. Narration creates order—a certain kind of certainty—in a radically uncertain world. The first-time reader, meanwhile, searches for a thread to untangle.

Like the first-time reader, our poor narrator is still terribly awfully apocalyptically uncertain. The narrator briefly describes the great minor uncertain grief she feels, a grief without object: “…I don’t know what I grieve for: my wife? my husband? my children, or myself? I can’t remember. My dreams are forgotten…” Is grief without object the problem of the postmodern, post-atomic world? “Schrödinger’s Cat” posits one version of uncertainty as a specific grief , a kind of sorrow for a loss that cannot be named. The story’s conclusion offers hope as an answer to this grief—another kind of uncertainty, but an uncertainty tempered in optimism.

This optimism has to thrive against a surreal apocalyptic backdrop of speed and heat—a world that moves too fast to comprehend, a world in which stove burners can’t be switched Off—we have only heat, fire, entropy. How did folks react? —

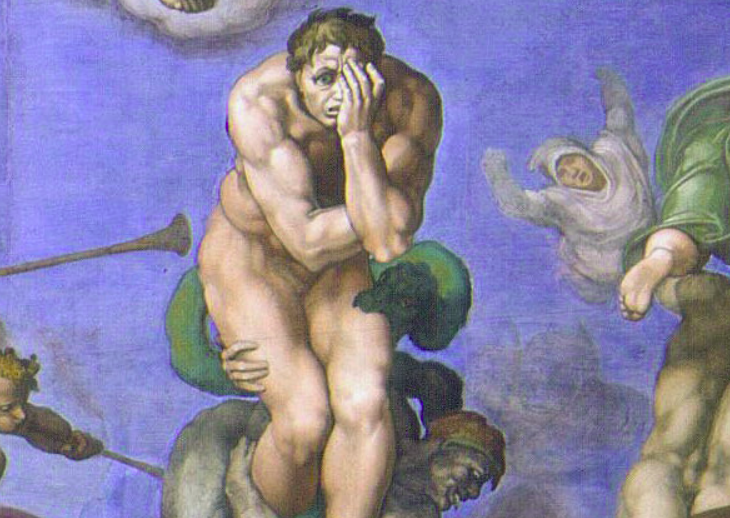

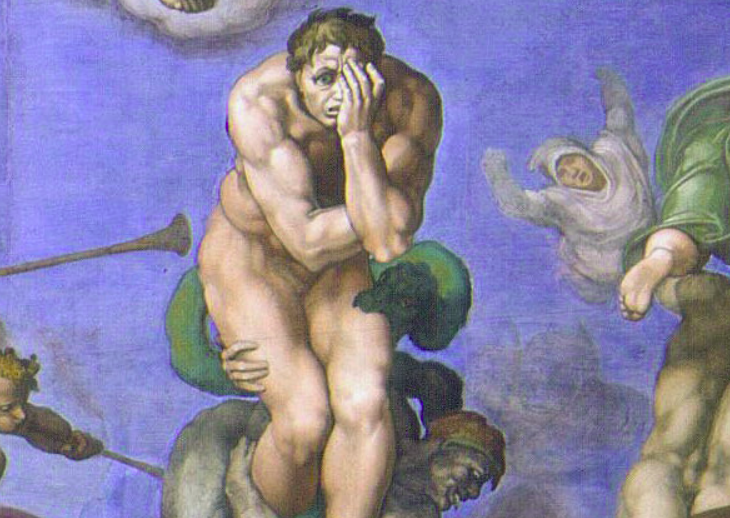

In the face of hot stove burners they acted with exemplary coolness. They studied, they observed. They were like the fellow in Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, who has clapped his hands over his face in horror as the devils drag him down to Hell—but only over one eye. The other eye is looking. It’s all he can do, but he does it. He observes. Indeed, one wonders if Hell would exist, if he did not look at it.

—Hey, like that’s Le Guin’s mythological take on Erwin Schrödinger’s thought experiment!—or at least, part of it.

(Hell exists because we keep one eye on it, folks. Look away, maybe).

I have failed to mention the titular cat thus far. Schrödinger’s cat is the Cheshire cat, the ultimate escape artist and trickster par excellence who triggers this tale (tail?!). He shows up to hang out with the narrator.

Le Guin peppers her story with little cat jokes that highlight the instability of language: “They reflect all day, and at night their eyes reflect.” As the thermodynamic heat of the universe cools around our narrator and the feline, the narrator remarks that the story’s setting is cooler— “Here as I said it is cooler; and as a matter of fact, this animal is cool. A real cool cat.” In “Schrödinger’s Cat,” Le Guin doubles her meanings and language bears its own uncertainty.

A dog enters into the mix. Le Guin’s narrator initially thinks he’s a mailman, but then “decides” he is a small dog. The narrator quickly decides that not only is the non-mailman a dog, she also decides that his name is Rover. In naming this entity, the narrator performs an act of agency in a world of entropy—she makes certain (at least momentarily) an uncertain situation.

Our boy Rover immediately calls out Schrödinger’s cat, and gives the narrator (and the reader) a fuzzy precis of the whole experiment, an experiment that will definitely give you a Yes or No answer: The cat is either alive or the cat is not alive at the end of our little quantum boxing. Poor Rover gives us a wonderful endorsement of the experiment: “So it is beautifully demonstrated that if you desire certainty, any certainty, you must create it yourself!” Rover gives us an unintentionally ironic definition of making meaning in a postmodern world. Agency falls to the role of the reader/agent, who must decide (narrate, choose, and write) in this fragmented world.

For Rover, Schrödinger’s thought experiment offers a certain kind of certitude: the cat is alive or dead, a binary, either/or. Rover wants to play out the experiment himself—force the cat into the box and get, like, a definitive answer. But the curious playful narrator pricks a hole in the experiment: “Why don’t we get included in the system?” the narrator questions the dog. It’s too much for him, a layer too weird on an already complex sitch. “I can’t stand this terrible uncertainty,” Rover replies, and then bursts into tears. (Our wordy-clever narrator remarks sympathy for “the poor son of a bitch”).

The narrator doesn’t want Rover to carry out the experiment, but the cat itself jumps into the box. Rover and narrator wait in a moment of nothingness before the somethingness of revelation might happen when they lift the lid. In the meantime, the narrator thinks of Pandora and her box:

I could not quite recall Pandora’s legend. She had let all the plagues and evils out of the box, of course, but there had been something else too. After all the devils were let loose, something quite different, quite unexpected, had been left. What had it been? Hope? A dead cat? I could not remember.

Le Guin tips her hand a bit here, like Nathaniel Hawthorne, the great dark romantic she is heir to; she hides her answer in ambiguous plain sight. Hope is the answer. But hope is its own radical uncertainty, an attitudinal answer to the postmodern problem—but ultimately a non-answer. The only certainty is non-certainty.

What of the conclusion? Well, spoiler: “The cat was, of course, not there,” when Rover and narrator open the box. But that’s not the end. The last lines of Le Guin’s story see “the roof of the house…lifted off just like the lid of a box” — so the setting of our tale this whole time, as we should have guessed, was inside the apocalyptic thought experiment of Schrödinger. Apocalyptic in all sense of the word—in the connotation of disaster, but also revelation. The revelation though is a revelation of uncertainty. In the final line, the narrator, musing that she will miss the cat, wonders “if he found what it was we lost.”

What I think Le Guin points to here as the “it” that we lost in these hot and fast times is the radical uncertainty of hope.