“Are we not Men?”

— The Island of Dr. Moreau, H.G. Wells (1896)

“A country, a people…Those are strange and very difficult ideas.”

— Four Ways to Forgivenss, Ursula K. Le Guin (1995)

—Each of the novels in Ursula K. Le Guin’s so-called Hainish cycle obliquely addresses Wells’s question by tackling those strange and very difficult ideas of “a country, a people.” The best of these Hainish books do so in a manner that synthesizes high-adventure sci-fi fantasy with dialectical philosophy.

—What am I calling here “the best”? Well—

The Left Hand of Darkness

Planet of Exile/City of Illusions (treat as one novel in two discursive parts)

The Dispossessed

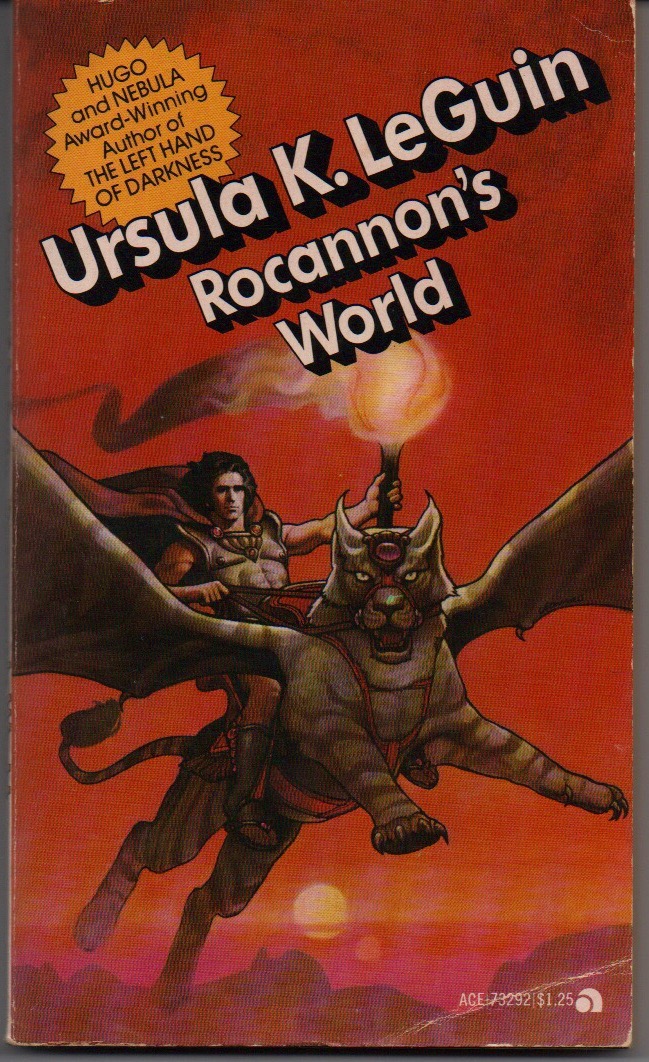

—(How oh how oh how dare I rank The Dispossessed—clearly a masterpiece, nay?—so low on that little list? It’s too dialectical, maybe? Too light on the, uh, high adventure stuff, on the fantasy and romance and sci-fi. Its ideas are too finely wrought, well thought out, expertly cooked (in contrast to the wonderful rawness of Rocannon’s World, for example). None of this is to dis The Dispossessed—it’s probably the best of the Hainish books, and the first one casual readers should attend to. (It was also the first one I read way back when in high school)).

—The novels in Le Guin’s so-called Hainish cycle are

Rocannon’s World (1966)

Planet of Exile (1966)

City of Illusions (1967)

The Left Hand of Darkness (1969)

The Dispossessed (1974)

The Word for World is Forest (1976)

Four Ways to Forgiveness (1995)

The Telling (2000)

—Okay, so I decided to include For Ways to Forgiveness in the above list even though most people wouldn’t call it a “novel” — but its four stories (novellas, really) are interconnected and tell a discrete story of two interconnected planets that are part of the Hainish world. And I pulled a quote from it above. So.

—I read, or reread, Le Guin’s so-called Hainish cycle close to the chronological order proposed by the science fiction writer Ian Watson. I don’t necessarily recommend this order.

—(I keep modifying “Hainish cycle” with “so-called” because the books aren’t really a cycle. Le Guin’s world-building isn’t analogous to Tolkien’s Middle Earth or Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. (Except when her world-building is analogous). But let us return to order).

People write me nice letters asking what order they ought to read my science fiction books in — the ones that are called the Hainish or Ekumen cycle or saga or something. The thing is, they aren’t a cycle or a saga. They do not form a coherent history. There are some clear connections among them, yes, but also some extremely murky ones. And some great discontinuities (like, what happened to “mindspeech” after Left Hand of Darkness? Who knows? Ask God, and she may tell you she didn’t believe in it any more.)

OK, so, very roughly, then:

Rocannon’s World, Planet of Exile, City of Illusions: where they fit in the “Hainish cycle” is anybody’s guess, but I’d read them first because they were written first. In them there is a “League of Worlds,” but the Ekumen does not yet exist.

—I agree with the author. Read this trilogy first. Read it as one strange book.

—(Or—again—pressed for time and wanting only the essential, read The Dispossessed and The Left Hand of Darkness—but you already knew that, no?).