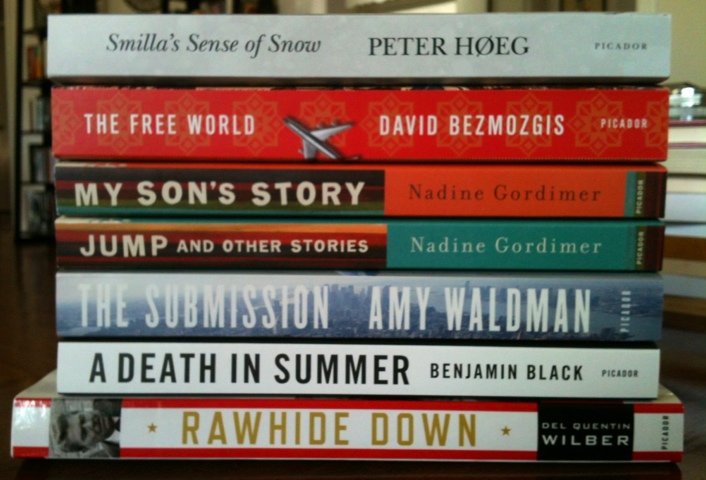

New and newish titles from the good people at Picador. A few highlights:

I read Peter Hoeg’s bestseller Smilla’s Sense of Snow over a decade ago; I recall reading it in a day or two, maybe as part of a long bus ride somewhere, and enjoying caustic Smilla’s murder investigation. It’s 20 years old now and getting the rerelease treatment. From Robert Nathan’s original 1993 review at The New York Times:

TRY this for an offer you could easily refuse. How would you like to be locked in a room for a couple of days with an irritable, depressed malcontent who also happens to be imperiously smart, bored and more than a little spoiled? Say no, and you will miss not only a splendid entertainment but also an odd and seductive meditation on the human condition. With “Smilla’s Sense of Snow,” his American debut following two previous books, the Danish novelist Peter Hoeg finds his own uncommon vein in narrative territory worked by writers as varied as Martin Cruz Smith and Graham Greene — the suspense novel as exploration of the heart. Mr. Hoeg’s heroine, Smilla Jaspersen, is the daughter of an Eskimo mother who was a nomadic native of Greenland and a wealthy Danish anesthesiologist father, parentage that endows her with the resilience of the frozen north and urban civilization’s existential malaise. One day just before Christmas, Smilla arrives at her Copenhagen apartment building to find a neighbor boy, 6-year-old Isaiah Christiansen, sprawled face down in the snow, dead after a fall from the roof of a nearby warehouse.

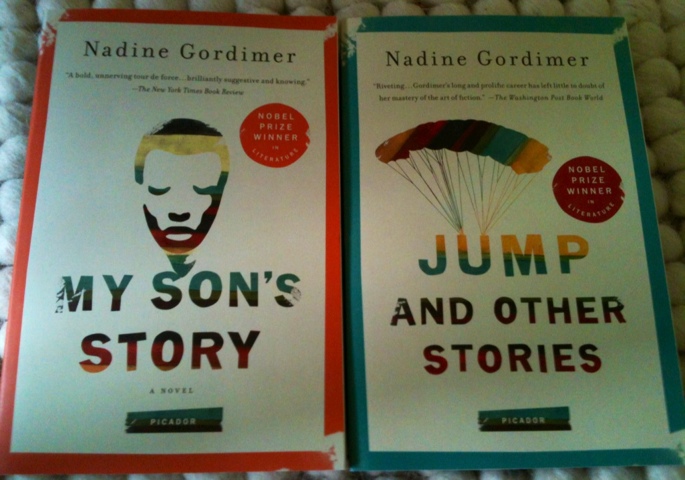

Love love love the covers for these pair by Nadine Gordimer—nice design work. I haven’t read Gordimer’s stuff — she’s a South African writer who won the Nobel in 1991 — so Jump and Other Stories seems like a good starting place. Here’s James Wood on Gordimer:

Gordimer’s talent is poetic and intellectual…Her best writing, sensuous, but aerated with deep intelligence, moving shrewdly between the serene claims of the poetic and the frantic compulsions of the political, makes her the lyrical analyst of an entire country

Amy Waldman’s The Submission is a 9/11 novel. Here’s Michiko Kakutani gushing in The New York Times:

A decade after 9/11, Amy Waldman’s nervy and absorbing new novel, “The Submission,” tackles the aftermath of such a terrorist attack head-on. The result reads as if the author had embraced Tom Wolfe’s famous call for a new social realism — for fiction writers to use their reporting skills to depict “this wild, bizarre, unpredictable, Hog-stomping baroque country of ours” — and in doing so, has come up with a story that has more verisimilitude, more political resonance and way more heart than Mr. Wolfe’s own 1987 best seller, “The Bonfire of the Vanities.”

A Death in the Summer is new in trade paperback. It’s another in the Quirke crime series from Benjamin Black — pen name of writer John Banville. Jacket copy:

On a sweltering summer afternoon, newspaper tycoon Richard Jewell—known to his many enemies as Diamond Dick—is discovered with his head blown off by a shotgun blast. But is it suicide or murder? For help with the investigation, Detective Inspector Hackett calls in his old friend Quirke, who has unusual access to Dublin’s elite.

Jewell’s coolly elegant French wife, Françoise, seems less than shocked by her husband’s death. But Dannie, Jewell’s high-strung sister, is devastated, and Quirke is surprised to learn that in her grief she has turned to an unexpected friend: David Sinclair, Quirke’s ambitious assistant in the pathology lab at the Hospital of the Holy Family. Further, Sinclair has been seeing Quirke’s fractious daughter Phoebe, and an unlikely romance is blossoming between the two. As a record heat wave envelops the city and the secret deals underpinning Diamond Dick’s empire begin to be revealed, Quirke and Hackett find themselves caught up in a dark web of intrigue and violence that threatens to end in disaster.

Tightly plotted and gorgeously written, A Death in Summer proves to the brilliant but sometimes reckless Quirke that in a city where old money and the right bloodlines rule, he is by no means safe from mortal danger.

Del Quentin Wilber’s Rawhide Down: The Near Assassination of Ronald Reagan demanded more of my attention than I thought it would. It’s tightly paced book, telegraphed in sharp language—but most of all, the story of John Hinckley is just too bizarre. Here’s a sample of the would

And if that’s not weird enough for you, check out Hinckley’s fantasy life: