Notes on Chapters 1-7 | Glows in the dark.

Notes on Chapters 8-14 | Halloween all the time.

Notes on Chapters 15-18 | Ghostly crawl.

Notes on Chapters 21-23 | Phantom gearbox.

Notes on Chapters 27-29 | We’re in for some dark ages, kid.

Chapter 30 opens in “The Vienna branch of MI3b, daytime, a modest-size office decorated with a movie poster of Lilian Harvey waltzing with Willy Fritsch in Der Kongreß tanzt and an ancient map of the Hapsburg Dual Monarchy.”

Der Kongreß tanzt (The Congress Dances) is a 1931 UFA production set in Vienna, 1815 — if you want to go down the rabbit hole, maybe start with this contemporary New York Times review of the film. The Congress Dances was Weimar UFA’s tentpole shot at competing with Hollywood; later the production company would be subsumed by the Nazis. A current throughout Pynchon’s works has been something like, resist the military-industrial-entertainment complex. It’s worth noting the emphasis on dancing here, a motif in Shadow Ticket. Is dancing a form of transcendent resistance? Or is it a narcotizing agent?

The Habsburg Dual Monarchy, formed in 1867 after the Austro-Prussian War, joined two distinct nations under one emperor — a kind of bilocation — leaving ethnic and nationalist tensions unresolved. These divisions weakened the empire, contributing to the instability that helped spark World War I and, after its collapse, left a fragmented Central Europe whose resentments helped set the stage for World War II.

We are in that stage-setting right now, in that fragmented, fragmenting Central Europe, in the office of British Military Intelligence Section 3 where secret agent couple Alf and Pip Quarrender have been called before “Station chief Arvo Thorp.” Thorp informs the Quarrenders that their asset Vassily Midoff is “seeking to join a motorcycle rally in progress at the moment” — the Trans-Trianon 2000 Tour of Hungary Unredeemed that everyone’s set out on — and “that someone must be sent round” to cut off that loose end posthaste. The Quarrenders are upset — “But he was ours, Thorp…Our bloke” — but orders are orders. They do question the rationale of the orders though, wondering if it was simply “too much effort to keep all [Vassily’s] allegiances straight.” Here we have a neat little summary of how some readers may feel sussing motives and plot points from Shadow Ticket.

Codebreaker Alf gets something proximal to an “answer” when he intercepts an encrypted message floating around various intelligence agencies: Vassily “has apparently been promoted to deputy operations officer of an unacknowledged narkomat, a Blavatskian brotherhood of psychical masters and adepts located someplace out in the wild Far East.” Pynchon further underlines Shadow Ticket’s haunted themes, bringing up Stalin’s “chief crypto genius Gleb Bokii [who] is also running a secret lab specializing in the paranormal.”

But Alf can’t fully crack the code (natch), receiving “only glimpses behind a cloak of dark intention at something on a scale far beyond trivialities of known politics or history, which one fears if ever correctly deciphered will yield a secret so grave, so countersacramental, that more than one government will go to any lengths to obtain and with luck to suppress it.” In a chilly series of sentences, Alf, pushed by “some invisible power,” continues chipping at the encryption against his better judgment. But the encryption is, well, cryptic, even as it portends a future yet to come (including the ominous not that Stalin, “threatened by supernatural forces [would] probably go after Jews first.”

Alf concludes that Vassily “may have gone mad, he may in fact have crossed a line forbidden or invisible to the likes of us, thrown by some occult switchwork over onto an alternate branch line of history.” The “alternative branch line” again evokes the novel’s themes of bilocation (which I’ve tried to enumerate in previous riffs).

(The bigger Pynchonian bilocation is frequently visible/invisible, in the spiritualist-materialist sense — which perhaps finds a moral corollary in convenient/inconvenient.)

So well and anyway–the Quarrenders track down the Russian Trans-Trianon caravan and locate Vassily, but he manages to escape on a Rio-bound zeppelin painted like a watermelon, to their relief.

“Hicks, Slide, and Zdeněk come rolling into a parts depot deep in the Transylvanian forest,” at the beginning of Chapter 31. (Slide is an American journalist; Zdeněk is a non-gigantic golem, if you need help keeping track.) They are on the Trans-Trianon 2000 motorcycle route, presumably tracking Hop Wingdale. Or Daphne Airmont. Or Bruno Airmont. Or…?

Here in “actual Transylvania, the vampire motherland itself,” the trio drives through “hairpin turns frequented by vengeful spirits, passages cursed by some local shaman, marsh life you wouldn’t want swarming around you after dark…And the bats of course.” According to Zdeněk these vampire bats “are the Unbreathing, who go about their business in a silence not even broken by pulsebeats.”

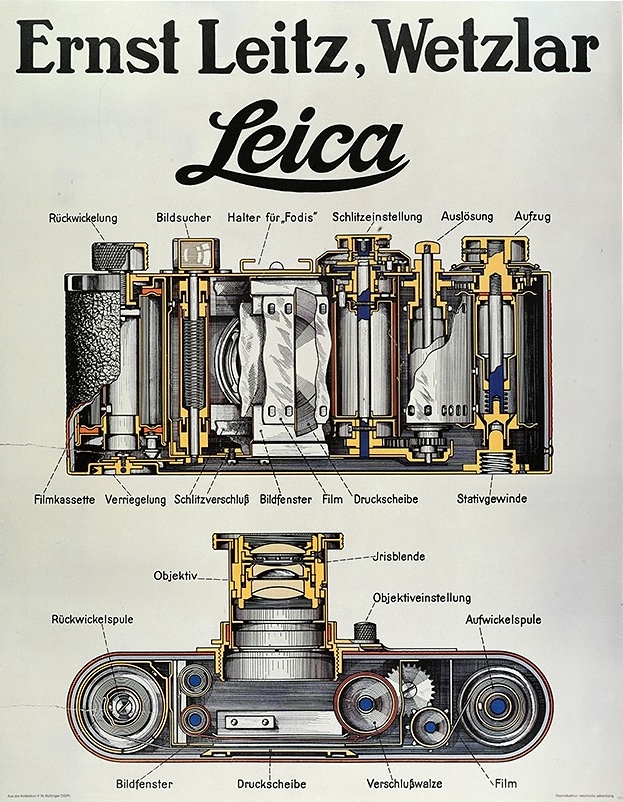

Slide’s brought along his Leica camera to “cover the supernatural angle,” but the pictures all end up blank: “a vampire’s allergy to silver, an ambivalence as to light itself…” I’ve foregrounded Shadow Ticket’s Gothic motifs and impulses throughout my notes. I don’t really know what I could add to, like, golems and vampires in Transylvania.

Noting that the Trans-Trianon 2000 motorcycle route allows for “impulses disallowed in normal society” to be acted upon, the narration then gives over to one of my favorite little bits in Shadow Ticket, a self-contained episode of “spontaneous pig rescue.” The pig in question is “a Mangalica, a popular breed in Hungary at the moment, curly-coated as a sheep, black upper half, blonde lower. And that face! One of the more lovable pig faces, surrounded by ringlets and curls.”

Pynchon’s porcophilia is well-documented, with pigs showing favorably throughout his work–particularly in Mason & Dixon and in Gravity’s Rainbow, where Tyrone Slothrop takes on the role (and costume) of Plechazunga, the Pig-Hero, and then later wanders through the Zone with a sweet pig as his companion-guide, while the narrator sings:

“A pig is a jolly companion,

Boar, sow, barrow, or gilt–

A pig is a pal, who’ll boost your morale,

Though mountains may topple and tilt.”

Back to Hicks: “wandering the compound one day hears a piano in the distance, recognizes the tune as ‘Star of the County Down,’ a longtime favorite of Irish drinkers he’s known.” It turns out that none other than Pip Quarrender is singing and playing the song — which she identifies as “Dives and Lazarus,” a traditional English folk song that that adapts a riff from the Gospel of Luke. Pips notes that it’s “technically it’s a Christmas carol, though uncomfortable for the average churchgoer given its rather keen element of class hostility.” We have here another bilocation, a song with two separate but real co-existing lives. (Throw in a little class warfare, too.)

Hicks then runs into Terike, who’s concerned that Ace Lomax is missing, on the run from she-knows-not-what (it’s Bruno). The chapter ends with “Zdeněk the golem [locating] Hop Wingdale en route to a Croatian guerrilla training camp near the Hungarian border.” He decides to go check it out.

The band pulls in to a “towering wooden cylinder set in a clearing, filled with the snarling of low-displacement bike engines.” Their gig is at a Wall of Death motor cycle stunt show.

Pynchon invokes the image of a wall of death late in Gravity’s Rainbow: “somewhere, out beyond the Channel, a barrier difficult as the wall of Death to a novice medium, Leftenant Slothrop, corrupted, given up on, creeps over the face of the Zone.” The metaphor here of course is the wall between the living and the dead.

It turns out that Ace Lomax has been stunt riding on the Wall of Death for tips. Prompted by the band, he sings a Western tune: “Things were so jake, at the O.K. Corral— / Till those Earps and Clantons came along—.” The fantasy here is of an unspoiled West which eventually succumbs to the violence of competing agencies.

Ace recognizes Hop and congratulates his being “still vertical.” He proceeds to tell the musician that Bruno Airmont had tried to get Ace to assassinate Hop, but he decided that wasn’t his gig and hit the road: “By nightfall he’s in Bratislava and slipping unnoticed in among a convoy of Trans-Trianon machinery.” In their discussion about the Wall of Death, Hop brings up motordrome physics: “Somebody said it’s safe long as you keep moving fast enough, something about centrifugal force.” We get here a repetition of one of Shadow Ticket’s major themes, neatly summed up by Stuffy Keegan back in Ch. 20: “as long as you can stay on the run, that’s the only time you’re really free.”

Ace then hits the road. He fails to check in back at the Trans-Trianon base camp, causing Terike’s cryptic road-adventuress face…to drift into disarray. She decides to light out looking for him.

The chapter ends with the narrator telling us that it turns “out that in some walled-in maze of a mountain town Ace has missed a turn…and ends up running on fumes.” He’s pursued by not only wolves but also the fascist Vladboys, “who also run this terrain in packs.” The fascist gang are on what I take to be dirt bikes, faster than Ace’s Harley. The last line, “Ace finds himself in the hands of the Vladboys,” sets up a nice opportunity for a big dramatic climactic rescue scene.