“Did you want to speak to me, Ivar?” Alexandra asked as she rose from the table. “Come into the sitting-room.”

The old man followed Alexandra, but when she motioned him to a chair he shook his head. She took up her workbasket and waited for him to speak. He stood looking at the carpet, his bushy head bowed, his hands clasped in front of him. Ivar’s bandy legs seemed to have grown shorter with years, and they were completely misfitted to his broad, thick body and heavy shoulders.

“Well, Ivar, what is it?” Alexandra asked after she had waited longer than usual.

Ivar had never learned to speak English and his Norwegian was quaint and grave, like the speech of the more old-fashioned people. He always addressed Alexandra in terms of the deepest respect, hoping to set a good example to the kitchen girls, whom he thought too familiar in their manners.

“Mistress,” he began faintly, without raising his eyes, “the folk have been looking coldly at me of late. You know there has been talk.”

“Talk about what, Ivar?”

“About sending me away; to the asylum.”

Alexandra put down her sewing-basket. “Nobody has come to me with such talk,” she said decidedly. “Why need you listen? You know I would never consent to such a thing.”

Ivar lifted his shaggy head and looked at her out of his little eyes. “They say that you cannot prevent it if the folk complain of me, if your brothers complain to the authorities. They say that your brothers are afraid—God forbid!—that I may do you some injury when my spells are on me. Mistress, how can any one think that?—that I could bite the hand that fed me!” The tears trickled down on the old man’s beard.

Alexandra frowned. “Ivar, I wonder at you, that you should come bothering me with such nonsense. I am still running my own house, and other people have nothing to do with either you or me. So long as I am suited with you, there is nothing to be said.”

Ivar pulled a red handkerchief out of the breast of his blouse and wiped his eyes and beard. “But I should not wish you to keep me if, as they say, it is against your interests, and if it is hard for you to get hands because I am here.”

Alexandra made an impatient gesture, but the old man put out his hand and went on earnestly:—

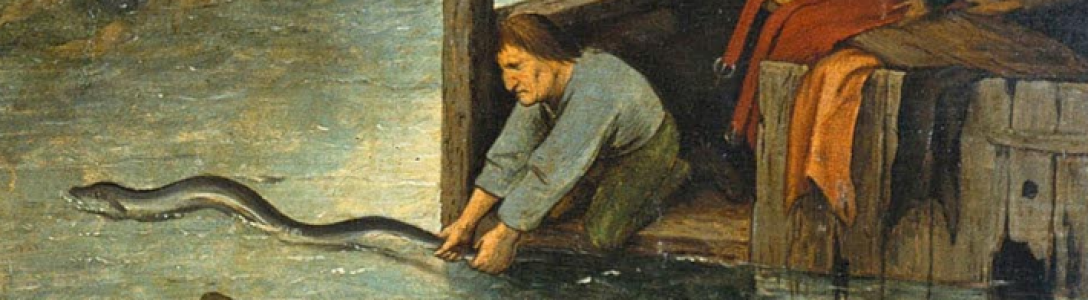

“Listen, mistress, it is right that you should take these things into account. You know that my spells come from God, and that I would not harm any living creature. You believe that every one should worship God in the way revealed to him. But that is not the way of this country. The way here is for all to do alike. I am despised because I do not wear shoes, because I do not cut my hair, and because I have visions. At home, in the old country, there were many like me, who had been touched by God, or who had seen things in the graveyard at night and were different afterward. We thought nothing of it, and let them alone. But here, if a man is different in his feet or in his head, they put him in the asylum. Look at Peter Kralik; when he was a boy, drinking out of a creek, he swallowed a snake, and always after that he could eat only such food as the creature liked, for when he ate anything else, it became enraged and gnawed him. When he felt it whipping about in him, he drank alcohol to stupefy it and get some ease for himself. He could work as good as any man, and his head was clear, but they locked him up for being different in his stomach. That is the way; they have built the asylum for people who are different, and they will not even let us live in the holes with the badgers. Only your great prosperity has protected me so far. If you had had ill-fortune, they would have taken me to Hastings long ago.”

As Ivar talked, his gloom lifted. Alexandra had found that she could often break his fasts and long penances by talking to him and letting him pour out the thoughts that troubled him. Sympathy always cleared his mind, and ridicule was poison to him.

From Willa Cather’s novel O Pioneers!

I read the novel back in college, enjoyed it, and read Cather’s later novel Death Comes for the Archbishop years after on my own. I picked up an audiobook version of O Pioneers! and started it this week, and it’s fabulous stuff—so controlled and precise, but also fluid, moving through time, memory, space, into consciousness, into the natural world—Cather’s evocation of nature on the Nebraska plains is particularly remarkable.

The novel is far more modernist than I recall as well. The narration slides slyly from a concrete third-person past-tense voice (what I often think of as the Plain Old Voice, if that makes sense), to a second-person clip that evokes a director telling his camera what to observe, to the workmanlike immediacy of a present-tense voice.

The passage above stands on its own, I think—but it also showcases several of the novel’s early themes, including the divide between the New World and the Old, alienation, and the ways in which conformity and routine are antithetical to the pioneer spirit that Americans like to trick themselves into believing they are heir to. The passage seems to rewrite Emily Dickinson’s “Much madness is divinest sense”; it also calls back to an early line from the book which I very much like: “A pioneer should have imagination, should be able to enjoy the idea of things more than the things themselves.”