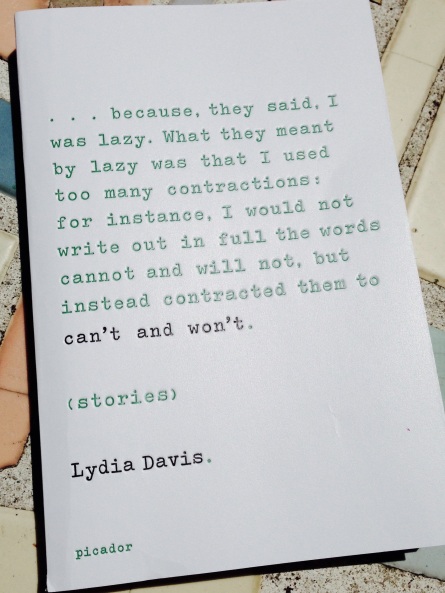

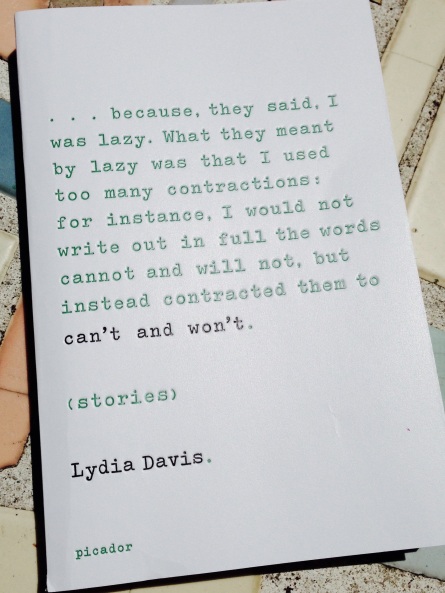

This is the part of the not-review where I include a picture I took of the book to accompany the not-review:

This is the part of the not-review where I briefly restage Lydia Davis’s publishing history to provide some context for readers new to her work.

This is the part of the not-review where I submit that anyone already familiar with Lydia Davis’s short fiction is likely to already hold an opinion on it that won’t (but could) be changed by Can’t and Won’t.

This is the part of the not-review where I dither pointlessly over whether or not the stories in Can’t and Won’t are actually stories or something other than stories.

This is the part of the not-review where I state that I don’t care if the stories in Can’t and Won’t are actually stories or something other than stories.

This is the part of the not-review where I explain that I have found a certain precise aesthetic pleasure in most of Can’t and Won’t that radiates from the savory contradictory poles of identification and alienation.

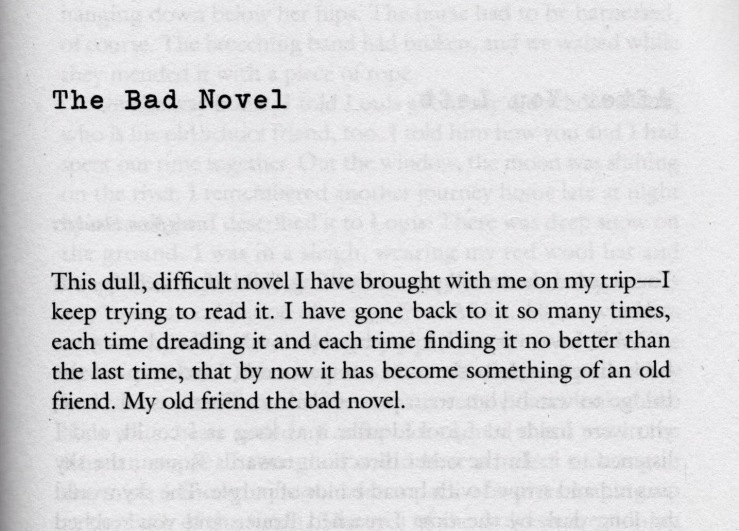

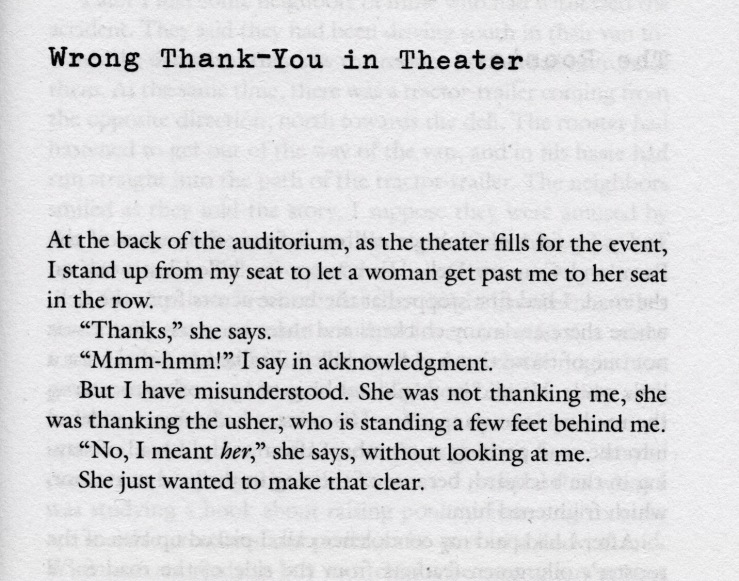

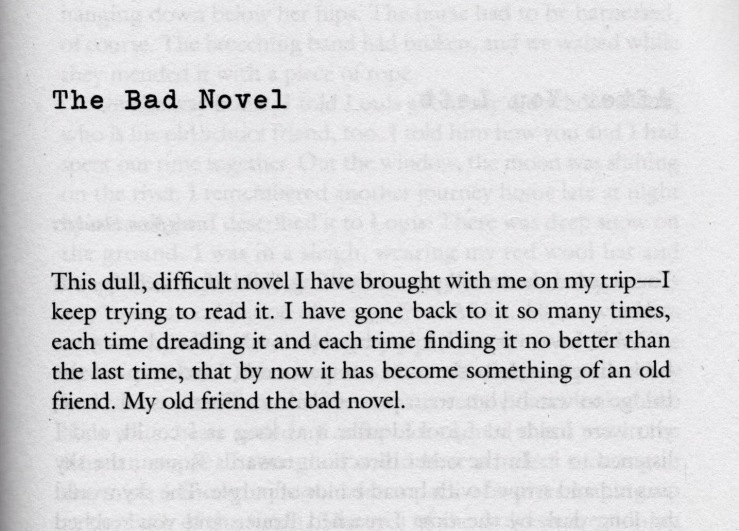

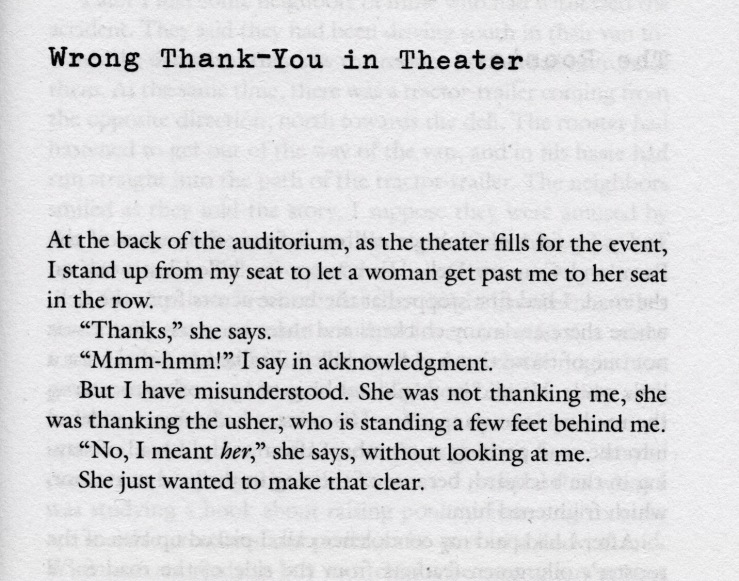

This is the part of the not-review where I cite an example of identification with Davis’s narrator-persona-speaker:

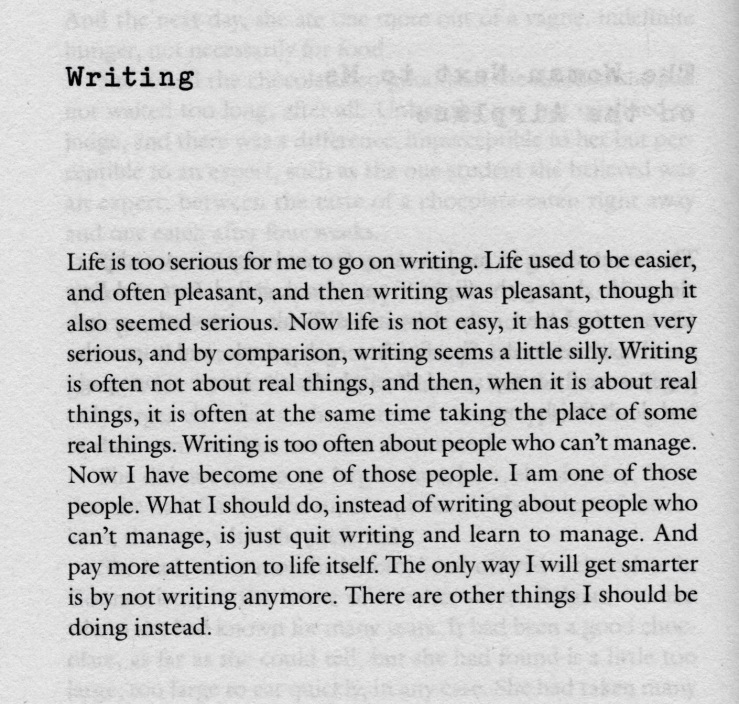

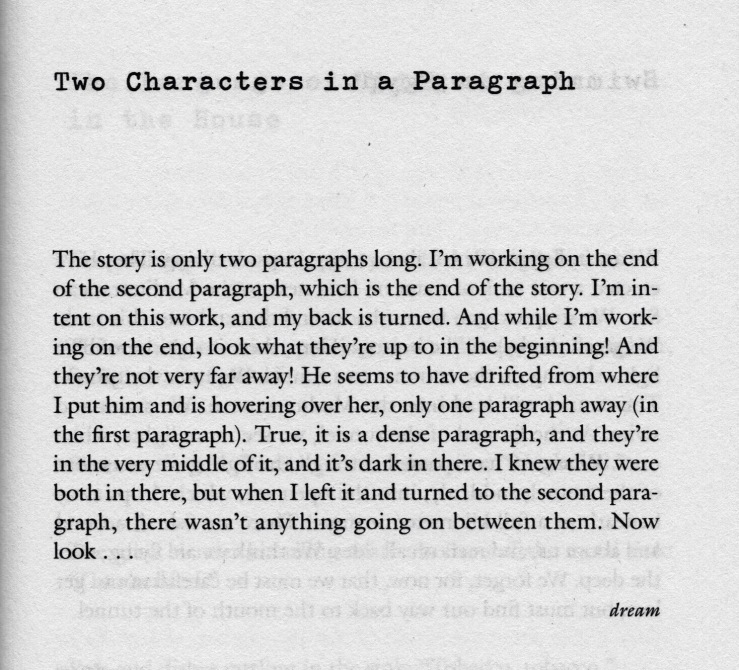

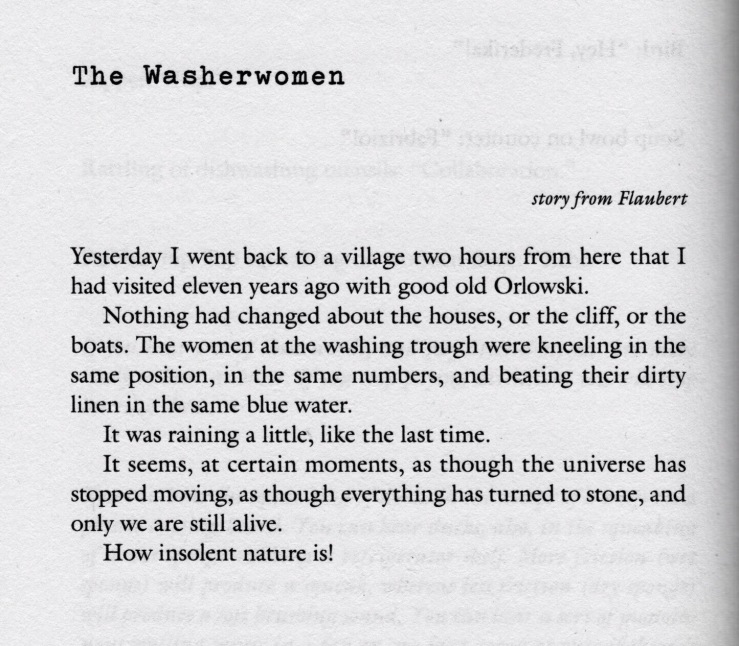

This is the part of the not-review where I claim that I used scans of the text to preserve the look and feel of Lydia Davis’s prose on the page.

This is the part of the not-review where I say that some of my favorite moments in Can’t and Won’t are Davis’s expressions of frustrated boredom with literature (or do I mean publishing?), like in the longer piece “Not Interested.”

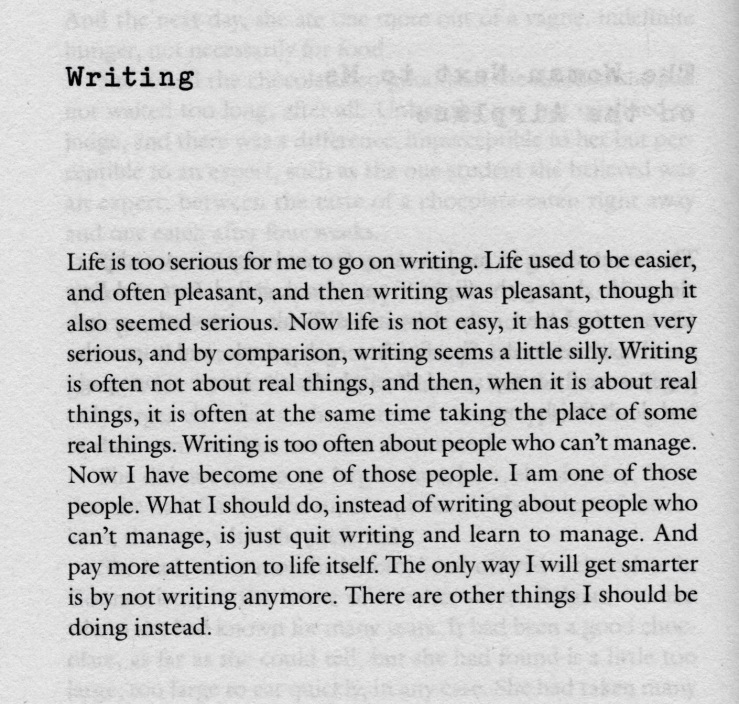

This is the part of the not-review where I point out that Davis’s speaker-narrator-persona expresses frustration with the act of writing itself:

This is the part of the not-review where I dither pointlessly over distinctions between Davis the author and Davis the persona-speaker-narrator.

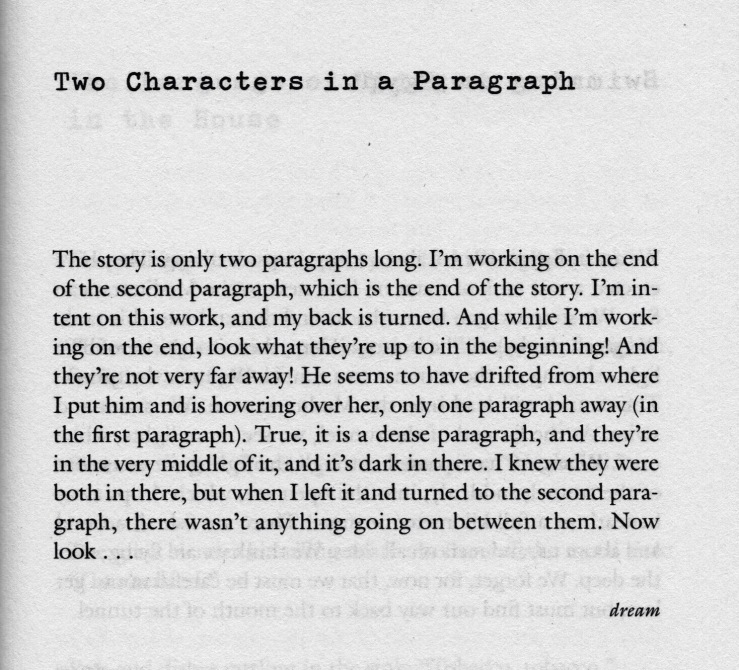

This is the part of the not-review where I point out that (previous dithering and frustration-with-writing aside) writing itself is a major concern of Can’t and Won’t:

This is the part of the not-review where I say that many of the stories in Can’t and Won’t are labeled dream, and I often found myself not really caring for these dreams (although I like the one above), but maybe I didn’t really care for the dreams because of their being tagged as dreams. (This is the part of the not-review where I point out that our eyes glaze over when anyone tells us their literal dreams).

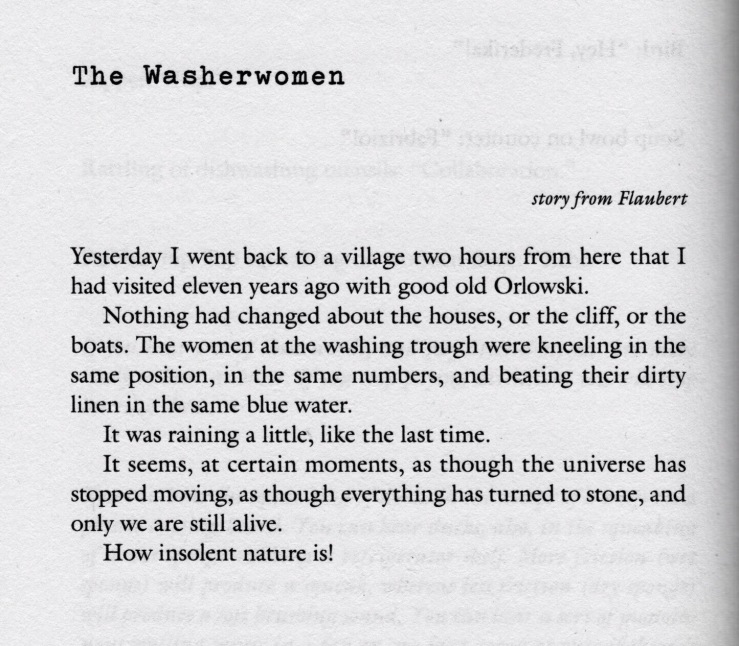

This is the part of the not-review where I transition from stories tagged dream to stories tagged story from Flaubert, like this one:

This is the part of the not-review where I say how much I liked the stories from Flaubert stories in Can’t and Won’t.

This is the part of the not-review where I mention Davis’s translation work, but don’t admit that I didn’t make it past the first thirty pages of her Madame Bovary.

This is the part of the not-review where I needlessly reference my review of The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis and point out that that collection is not so collected now.

This is the part of the not-review where I pointlessly dither over post-modernism, post-postmodernism, and Davis’s place in contemporary fiction. (This is the part of the not-review where I needlessly cram in the names of other authors, like Kafka and Walser and Bernhard and Markson and Adler and Miller &c.).

This is the part of the not-review where I claim that nothing I’ve written matters because Davis makes me laugh (this is also the part of the not-review where I use the adverb “ultimately,” a favorite crutch):

This is the part of the not-review where I point out that Can’t and Won’t is not for everybody, but I very much enjoyed it.

This is the part of the not-review where I mention that the publisher is FS&G/Picador, and that the book is available in the usual formats.