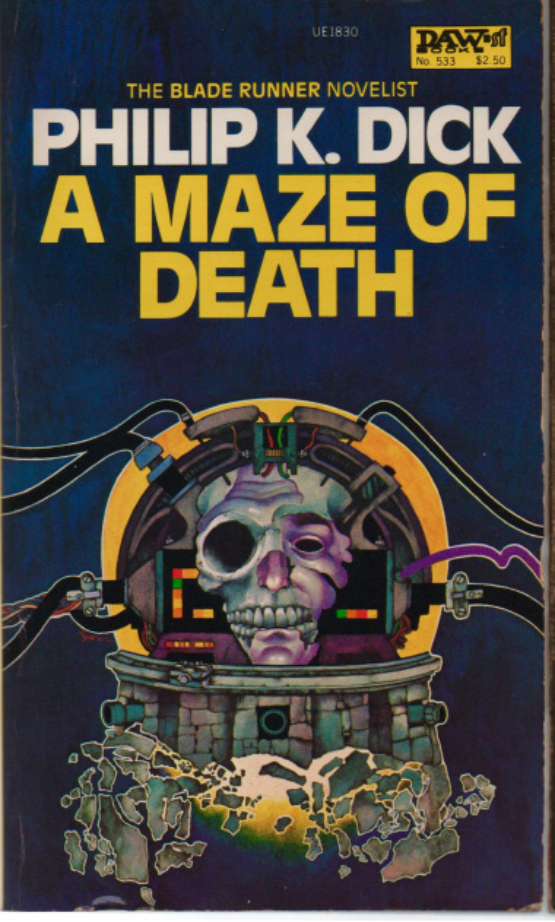

I finished Philip K. Dick’s 1970 novel A Maze of Death this afternoon. The end made me tear up a little, unexpectedly. It’s a sad end, profoundly sad in some ways, and the unexpectedness of the sadness, is, like, particularly sad.

Sad because I didn’t quite expect (hence that adverb unexpectedly) Dick to stick any kind of ending, what, after nearly 200 pages of cardboard characters wandering through a pulp fiction death maze, ventriloquized by the author to perform monologues on consciousness and perception and reality and religion and prayer and faith and afterlife and salvation and so on and so on and so on.

A Maze of Death has some strong moments and strong images—one-way space shuttles, organic 3-D printers, riffs on a deity that would necessarily absorb the concept of a non-deity, a cosmic recapitulation of Odin, space sex, etc.—but on the whole A Maze of Death peters out towards the end, its energy sapped as Dick tires of revolving through (and killing off) the cast of characters (and consciousnesses) he’s assembled in his Haunted (Space) House. The thin allegory he’s patched together crumbles. Or perhaps it was only an allegory assembled for its author’s sad delight. In any case, the whole does not cohere. But no matter.

Too, A Maze of Death suffers perhaps in comparison to its twin, Dick’s bouncier 1969 ensemble satire Ubik. Hell, Ubik probably peters out too, but it’s funnier and sharper. Still: A Maze of Death delivers a strong conclusion, a thesis statement that will resonate with anyone who’s ever envied a machine’s “Off” switch.

But book reviews aren’t supposed to start with endings, right?

What is A Maze of Death about? I mean, that’s what a book review is supposed to do, maybe? Give up some of the plot, the gist, right? The short short answer is Death. (And, like, how does consciousness mediate the ultimate promise of a life-maze that leads to Death, the apparent undoing of consciousness?). But wait, that’s not the plot, that’s like, theme, which is just a way of condensing the plot. This paragraph has gotten us nowhere. I’m going to get up off my ass and walk across the room I’m in to pick up Lawrence Sutin’s 1989 biography of PKD, Divine Invasions and crib from the “Chronological Survey and Guide” at its end. Okay, here, from the entry for Maze:

A group of colonists encounter inexplicable doings—including brutal murders—on the supposedly uninhabited planet Delmark-O. They then learn the truth of Milton’s maxim that the mind creates its own heavens and hells. … In his forward to Maze Phil cites the help of William Sarill in creating the “abstract, logical” religion posed in the novel; Sarill, in interview, says he only listened as Phil spun late-night theories.

—Okay, wait—I promise I’ll return to Sutin’s lucid summary—but Damn, that’s it right there— “Phil spun late-night theories” —much of Maze reads like a late night amphetamine rant about consciousness, man—

The plots of Eye [in the Sky], Ubik, and Maze are strikingly similar: A group of individuals find themselves in a perplexing reality state and try to use each other’s individual perceptions (idios kosmos) to make sense of what is happening to them all (koinos kosmos). Only in Eye, written ten years earlier, is the effort successful. In Ubik and Maze, by contrast, individual insight and faith are the only means of piercing the reality puzzle. In Maze, Seth Morley alone escapes the dire fate of his fellow twenty-second-century Delmark-O “colonists” (who are in truth…

—Okay, wait, it looks like Sutin is eager to spoil the ending there—but honestly, the ending that I found so satisfying wasn’t the twist that Sutin goes on to describe in his summary. The ending that Dick gives to his main viewpoint character Seth Morley that I found so moving had nothing to do with plot. Sutin’s line “Morely alone escapes” echoes the actual language of Dick’s novel, which echoes the end of Moby-Dick, where Ishmael alone escapes the wreckage of the Pequod, which in turn echoes the book of Job, where a witness returns from disaster to exclaim, I only am escaped alone to tell thee. This is the core of storytelling, I suppose: witnessing, enduring, and telling again. But Dick’s Morely wants an out, an off switch, a way to break the circuit, to escape the maze. The end of the novel—am I spoiling, after I cut Sutin off for fear of spoiling? Very well, I spoil—the end of the novel posits storytelling as a kind of survival mechanism against the backdrop of the existential horror of endless and apparently meaningless space. And yet the hero Morely still wants out of the story, and Dick lets him out. Out into non-story, out into a kind of plant-like existence—life without consciousness, life without a story.

But what’s the story the others, the rest of the maze’s ensemble, create?—

There is a quaternity of gods in Maze—an admixture of Gnosticism, neo-Platonism, and Christianity; the Mentafacturer, who creates (God); the Intercessor, who through sacrifice lifts the Curse on creation (Christ); the Walker-on-Earth, who gives solace (Holy Spirit); and the Form Destroyer, whose distance from the divine spurs entropy (Satan/Archon/Demiurge)/ The tench, an old inhabitant of Delmark-O, is Phil’s “cypher” for Christ.

The “tench” is originally introduced as a kind of 3-D printer thing and I didn’t read it as a Christ figure at all, but what the hell do I know. In fact, I took the name (and figuration) to be a composite of the tensions between the characters—the allegorical forces at work in Dick’s muddy made-up late-night religion.

Anyway, I suppose you get some of the flavor of the novel there, dear reader—a mishmash of metaphysical mumbo jumbo, filtered through touches (and tenches) of space opera and good old fashioned haunted housery. A Maze of Death is a messy space horror that threatens to leave its readers unsatisfied right up until the final moments wherein it rings its sad coda, a reverberation that nullifies all its previous twists and turns in a soothing wash of emptiness. Not the best starting place for PKD, but I’m very glad I read it.