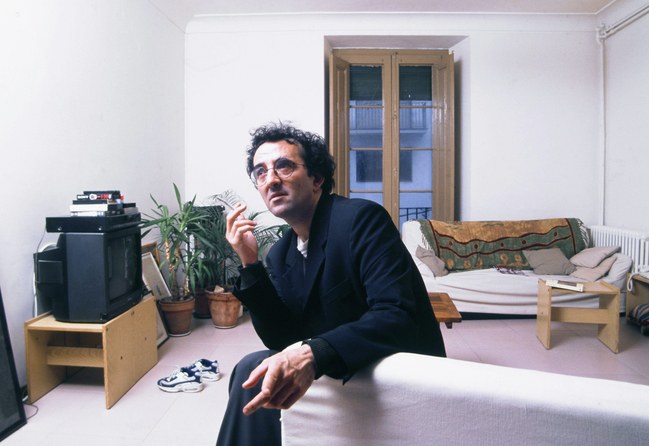

There’s an interesting review of Roberto Bolaño’s posthumous novel The Spirit of Science Fiction in the The New Yorker The review’s author, editor and translator Valerie Miles, read Bolaño’s novel through/against the work of the American Beats—William S. Burroughs and Jack Kerouac, specifically. From Miles’ review:

From 2008 to 2014, during the charged emergence of Bolaño in translation, I worked behind the scenes with the writer’s estate, reading through roughly fourteen thousand six hundred papers in his archive and helping to prepare his posthumous work. Bolaño, it should be said, saved everything. His archive includes notebooks, diaries, letters, magazines, war games, postcards, photos, typescripts, newspaper clippings, and an extensive library. (“I even found one of those paper napkins from a bar in Mexico,” his widow, Carolina López, has said, at a press conference.) The wealth of material makes it easy to locate Bolaño’s fixations at a given time, and much of my efforts involved establishing a chronology of when his work was written—a chronology that became a central part of the first exhibition dedicated to his papers, which I curated together with the Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona, in 2013.

That chronology also shed light on just how much “The Spirit of Science Fiction” was informed by poetry, and specifically by Bolaño’s reading of the Beats. In 1978, around the time Bolaño first began writing fiction in earnest, he wrote in his diary, “I write verses, dream of a novel.” During that time, he read William S. Burroughs daily and often commented on the writer’s work. (Burroughs was the “ice shard that would never melt,” he writes in his essay collection “Between Parentheses,” “the eye that never closes.”) In an early version of “The Spirit of Science Fiction,” Burroughs was the contact person for the young Chileans. Bolaño was also influenced by Burroughs’s approach to structure; he was fascinated by “Naked Lunch” and by the collage-like experimentation of “Nova Express.” He even borrowed some of Burroughs’s methods, riffing on Burroughs’s “cut-up” technique in his own verse.