A great shout went up near the doorway, bodies flowed toward a fattish pale young man who’d appeared carrying a leather mailsack over his shoulder.

“Mail call,” people were yelling. Sure enough, it was, just like in the army. The fat kid, looking harassed, climbed up on the bar and started calling names and throwing envelopes into the crowd. Fallopian excused himself and joined the others.

Metzger had taken out a pair of glasses and was squinting through them at the kid on the bar. “He’s wearing a Yoyodyne badge. What do you make of that?”

“Some inter-office mail run,” Oedipa said.

“This time of night?”

“Maybe a late shift?” But Metzger only frowned. “Be back,” Oedipa shrugged, heading for the ladies’ room.

On the latrine wall, among lipsticked obscenities, she noticed the following message, neatly indited in engineering lettering:

“Interested in sophisticated fun? You, hubby, girl friends. The more the merrier. Get in touch with Kirby, through WASTE only. Box 7391. L. A.”

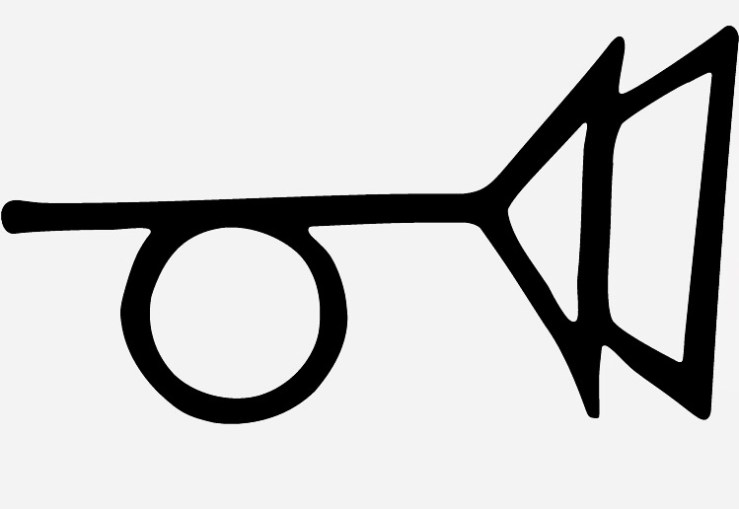

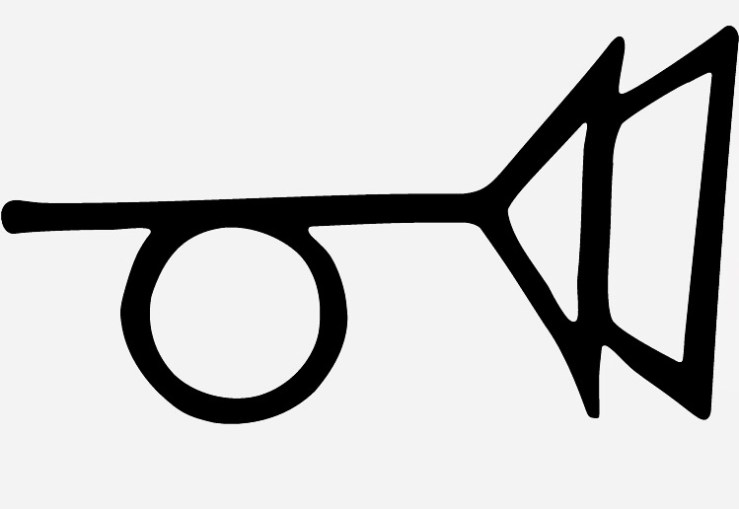

WASTE? Oedipa wondered. Beneath the notice, faintly in pencil, was a symbol she’d never seen before, a loop, triangle and trapezoid, thus:

It might be something sexual, but she somehow doubted it. She found a pen in her purse and copied the address and symbol in her memo book, thinking: God, hieroglyphics. When she came out Fallopian was back, and had this funny look on his face.

“You weren’t supposed to see that,” he told them. He had an envelope. Oedipa could see, instead of a postage stamp, the handstruck initials PPS.

“Of course,” said Metzger. “Delivering the mail is a government monopoly. You would be opposed to that.”

Fallopian gave them a wry smile. “It’s not as rebellious as it looks. We use Yoyodyne’s inter-office delivery. On the sly. But it’s hard to find carriers, we have a big turnover. They’re run on a tight schedule, and they get nervous. Security people over at the plant know something’s up. They keep a sharp eye out. De Witt,” pointing at the fat mailman, who was being hauled, twitching, down off the bar and offered drinks he did not want, “he’s the most nervous one we’ve had all year.”

“How extensive is this?” asked Metzger.

“Only inside our San Narciso chapter. They’ve set up pilot projects similar to this in the Washington and I think Dallas chapters. But we’re the only one in California so far. A few of your more affluent type members do wrap their letters around bricks, and then the whole thing in brown paper, and send them Railway Express, but I don’t know . . .”

“A little like copping out,” Metzger sympathized.

“It’s the principle,” Fallopian agreed, sounding defensive. “To keep it up to some kind of a reasonable volume, each member has to send at least one letter a week through the Yoyodyne system. If you don’t, you get fined.” He opened his letter and showed Oedipa and Metzger.

Dear Mike, it said, how are you? Just thought I’d drop you a note. How’s your book coming? Guess that’s all for now. See you at The Scope.

“That’s how it is,” Fallopian confessed bitterly, “most of the time.”

“What book did they mean?” asked Oedipa.

Turned out Fallopian was doing a history of private mail delivery in the U. S., attempting to link the Civil War to the postal reform movement that had begun around 1845. He found it beyond simple coincidence that in of all years 1861 the federal government should have set out on a vigorous suppression of those independent mail routes still surviving the various Acts of ’45, ’47, ’51 and ’55, Acts all designed to drive any private competition into financial ruin. He saw it all as a parable of power, its feeding, growth and systematic abuse, though he didn’t go into it that far with her, that particular night. All Oedipa would remember about him at first, in fact, were his slender build and neat Armenian nose, and a certain affinity of his eyes for green neon.

So began, for Oedipa, the languid, sinister blooming of The Tristero.

From The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon.