Leonora Carrington’s novel The Hearing Trumpet begins with its nonagenarian narrator forced into a retirement home and ends in an ecstatic post-apocalyptic utopia “peopled with cats, werewolves, bees and goats.” In between all sorts of wild stuff happens. There’s a scheming New Age cult, a failed assassination attempt, a hunger strike, bee glade rituals, a witches sabbath, an angelic birth, a quest for the Holy Grail, and more, more, more.

Composed in the 1950s and first published in 1974, The Hearing Trumpet is new in print again for the first time in nearly two decades from NYRB. NYRB also published Carrington’s hallucinatory memoir Down Below a few years back, around the same time as Dorothy issued The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington. Most people first come to know Carrington through her stunning, surreal paintings, which have been much more accessible (because of the internet) than her literature. However, Dorothy’s Complete Stories brought new attention to Carrington’s writing, a revival continued in this new edition of The Hearing Trumpet.

Readers familiar with Carrington’s surreal short stories might be surprised at the straightforward realism in the opening pages of The Hearing Trumpet. Ninety-two-year-old narrator Marian Leatherby lives a quiet life with her son and daughter-in-law and her tee-vee-loving grandson. They are English expatriates living in an unnamed Spanish-speaking country, and although the weather is pleasant, Marian dreams of the cold, “of going to Lapland to be drawn in a vehicle by dogs, woolly dogs.” She’s quite hard of hearing, but her sight is fine, and she sports “a short grey beard which conventional people would find repulsive.” Conventional people will soon be pushed to the margins in The Hearing Trumpet.

Marian’s life changes when her friend Carmella presents her with a hearing trumpet, a device “encrusted with silver and mother o’pearl motives and grandly curved like a buffalo’s horn.” At Carmella’s prompting, Marian uses the trumpet to spy on her son and daughter-in-law. To her horror, she learns they plan to send her to an old folks home. It’s not so much that she’ll miss her family—she directs the same nonchalance to them that she affords to even the most surreal events of the novel—it’s more the idea that she’ll have to conform to someone else’s rules (and, even worse, she may have to take part in organized sports!).

The old folks home is actually much, much stranger than Marian could have anticipated:

First impressions are never very clear, I can only say there seemed to be several courtyards , cloisters , stagnant fountains, trees, shrubs, lawns. The main building was in fact a castle, surrounded by various pavilions with incongruous shapes. Pixielike dwellings shaped like toadstools, Swiss chalets , railway carriages , one or two ordinary bungalows, something shaped like a boot, another like what I took to be an outsize Egyptian mummy. It was all so very strange that I for once doubted the accuracy of my observation.

The home’s rituals and procedures are even stranger. It is not a home for the aged; rather, it is “The Institute,” a cult-like operation founded on the principles of Dr. and Mrs. Gambit, two ridiculous and cruel villains who would not be out of place in a Roald Dahl novel. Dr. Gambit (possibly a parodic pastiche of George Gurdjieff and John Harvey Kellogg) represents all the avarice and hypocrisy of the twentieth century. His speech is a satire of the self-important and inflated language of commerce posing as philosophy, full of capitalized ideals: “Our Teaching,” “Inner Christianity,” “Self Remembering” and so on. Ultimately, it’s Gambit’s constricting and limited patriarchal view of psyche and spirit that the events in The Hearing Trumpet lambastes.

Marian soon finds herself entangled in the minor politics and scheming of the Institute, even as she remains something of an outsider on account of her deafness. She’s mostly concerned with getting an extra morsel of cauliflower at mealtimes—the Gambits keep the women undernourished. She eats her food quickly during the communal dinner, and obsesses over the portrait of a winking nun opposite her seat at the table:

Really it was strange how often the leering abbess occupied my thoughts. I even gave her a name, keeping it strictly to myself. I called her Doña Rosalinda Alvarez della Cueva, a nice long name, Spanish style. She was abbess, I imagined, of a huge Baroque convent on a lonely and barren mountain in Castile. The convent was called El Convento de Santa Barbara de Tartarus, the bearded patroness of Limbo said to play with unbaptised children in this nether region.

Marian’s creative invention of a “Doña Rosalinda Alvarez della Cueva” soon somehow passes into historical reality. First, she receives a letter from her trickster-aid Carmella, who has dreamed about a nun in a tower. “The winking nun could be no other than Doña Rosalinda Alvarez della Cueva,” remarks Marian. “How very mysterious that Carmella should have seen her telepathically.” Later, Christabel, another member/prisoner of the Institute helps usher Marian’s fantasy into reality. She confirms that Marian’s name for the nun is indeed true (kinda sorta): “‘That was her name during the eighteenth century,’ said Christabel. ‘But she has many many other names. She also enjoys different nationalities.'”

Christabel gives Marian a book entitled A True and Faithful Rendering of the Life of Rosalinda Alvarez and the next thirty-or-so pages gives way to this narrative. This text-within-a-text smuggles in other texts, including a lengthy letter from a bishop, as well as several ancient scrolls. There are conspiracies afoot, schemes to keep the Holy Grail out of the hands of the feminine power the Abbess embodies. There are magic potions and an immortal bard. There is cross-dressing and a strange monstrous pregnancy. There are the Knights Templar.

Carrington’s prose style in these texts-within-texts diverges considerably from the even, wry calm of Marian’s narration. In particular, there’s a sly control to the bishop’s letter, which reveals a bit-too-keen interest in teenage boys. These matryoshka sections showcase Carrington’s rhetorical range while also advancing the confounding plot. They recall The Courier’s Tragedy, the play nested in Thomas Pynchon’s 1965 novel The Crying of Lot 49. Both texts refer back to their metatexts, simultaneously explicating and confusing their audiences while advancing byzantine plot points and arcane themes.

Indeed, the tangled and surreal plot details of The Hearing Trumpet recall Pynchon’s oeuvre in general, but like Pynchon’s work, Carrington’s basic idea can be simplified to something like—Resistance to Them. Who is the Them? The patriarchy, the fascists, the killers. The liars, the cheaters, the ones who make war in the name of order. (One resister, the immortal traveling bard Taliesin, shows up in both the nested texts and later the metatext proper, where he arrives as a postman, recalling the Trystero of The Crying of Lot 49.)

The most overt voice of resistance is Marian’s best friend Carmella. Carmella initiates the novel by giving Marian the titular hearing trumpet, and she acts as a philosophical foil for her friend. Her constant warning that people under seventy and over seven should not be trusted becomes a refrain in the novel. Before Marian is shipped off to the Institution, Carmella already plans her escape, a scheme involving machine guns, rope, and other implements of adventure. Although she loves animals, Carmella is even willing to kill any police dogs that might guard the Institution and hamper their escape:

Police dogs are not properly speaking animals. Police dogs are perverted animals with no animal mentality. Policemen are not human beings so how can police dogs be animals?

Late in the novel, Carmella delivers perhaps the most straightforward thesis of The Hearing Trumpet:

It is impossible to understand how millions and millions of people all obey a sickly collection of gentlemen that call themselves ‘Government!’ The word, I expect, frightens people. It is a form of planetary hypnosis, and very unhealthy. Men are very difficult to understand… Let’s hope they all freeze to death. I am sure it would be very pleasant and healthy for human beings to have no authority whatever. They would have to think for themselves, instead of always being told what to do and think by advertisements, cinemas, policemen and parliaments.

Carmella’s dream of an anarchic utopia comes to pass.

How?

Well, there’s a lot to it, and I’d hate to spoil the surrealist fun. Let’s just say that Marian’s Grail quest scores a big apocalyptic win for the Goddess, thanks to “an army of bees, wolves, seven old women, a postman, a Chinaman, a poet, an atom-driven Ark, and a werewoman.” No conventional normies who might find Marian’s beard repulsive here.

With its conspiracy theories within conspiracy theories and Templar tales, The Hearing Trumpet will likely remind many readers of Umberto Eco’s 1988 novel Foucault’s Pendulum (or one of its ripoffs). The Healing Trumpet’s surreal energy also recalls Angela Carter’s 1972 novel The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman. And of course, the highly-imagistic, ever-morphing language will recall Carrington’s own paintings, as well as those of her close friend Remedios Varo (who may have been the basis for Carmella), and their surrealist contemporaries (like Max Ernst) and forebears (like Hieronymus Bosch).

This new edition of The Hearing Trumpet includes an essay by the novelist Olga Tokarczuk (translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones) which focuses on the novel as a feminist text. (Tokarczuk also mentions that she first read the novel without knowing who Carrington was). The new edition also includes black and white illustrations by Carrington’s son, Pablos Weisz Carrington (I’ve included a few in this review). As far as I can tell, these illustrations seem to be slightly different from the illustrations included in the 2004 edition of The Hearing Trumpet published by Exact Change. That 2004 edition has been out of print for ages and is somewhat hard (or really, expensive) to come by (I found a battered copy few years ago for forty bucks). NYRB’s new edition should reach the wider audience Carrington deserves.

Some readers will find the pacing of The Hearing Trumpet overwhelming, too frenetic. It moves like a snowball, gathering images, symbols, motifs into itself in an ever-growing, ever-speeding mass. Other readers may have difficulty with its ever-shifting plot. Nothing is stable in The Hearing Trumpet; everything is liable to mutate, morph, and transform. Those are my favorite kinds of novels though, and I loved The Hearing Trumpet—in particular, I loved its tone set against its imagery and plot. Marian’s narration is straightforward, occasionally wry, but hardly ever astonished or perplexed by the magical and wondrous events she takes part in. There’s a lot I likely missed in The Hearing Trouble—Carrington lards the novel with arcana, Jungian psychology, magical totems, and more more more—but I’m sure I’ll find more the next time I read it. Very highly recommended.

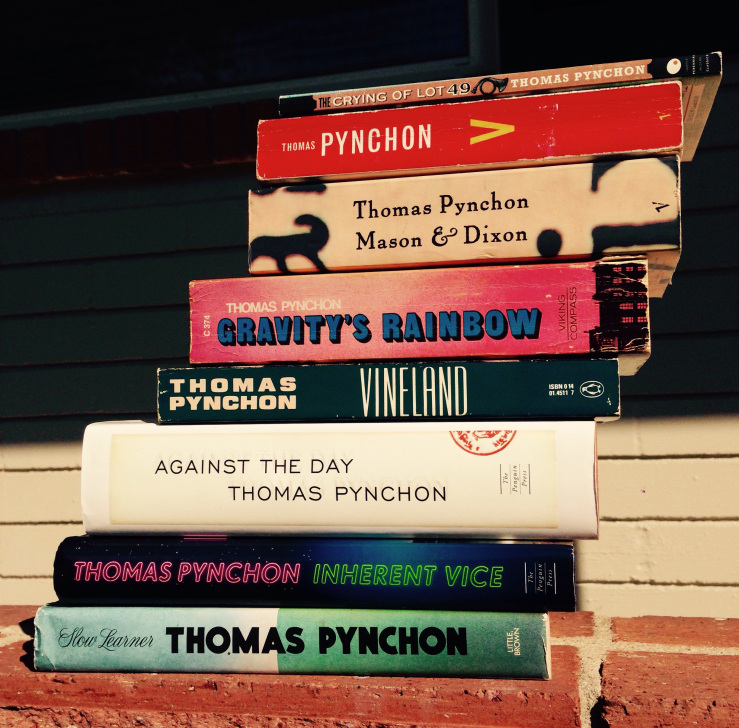

To date, Thomas Ruggles Pynchon (American, b. 1937), has published eight novels and one collection of short stories. These books were published between 1963 and 2013. On this day, Thomas Ruggles Pynchon’s 81st birthday, I present my ranking of his novels. My ranking is completely subjective, essentially incomplete (in that I haven’t read two of Pynchon’s novels all the way through), and thoroughly unnecessary. My ranking should be disregarded, but I do not think it should be treated with any malice. You are most welcome to make your own ranking in the comments section of this post, or perhaps elsewhere online, or on a scrap of your own paper, or in personal remarks to a friend or loved one, etc. I have not included the short story collection Slow Learner (1984) in this ranking because it is not a novel.

To date, Thomas Ruggles Pynchon (American, b. 1937), has published eight novels and one collection of short stories. These books were published between 1963 and 2013. On this day, Thomas Ruggles Pynchon’s 81st birthday, I present my ranking of his novels. My ranking is completely subjective, essentially incomplete (in that I haven’t read two of Pynchon’s novels all the way through), and thoroughly unnecessary. My ranking should be disregarded, but I do not think it should be treated with any malice. You are most welcome to make your own ranking in the comments section of this post, or perhaps elsewhere online, or on a scrap of your own paper, or in personal remarks to a friend or loved one, etc. I have not included the short story collection Slow Learner (1984) in this ranking because it is not a novel.