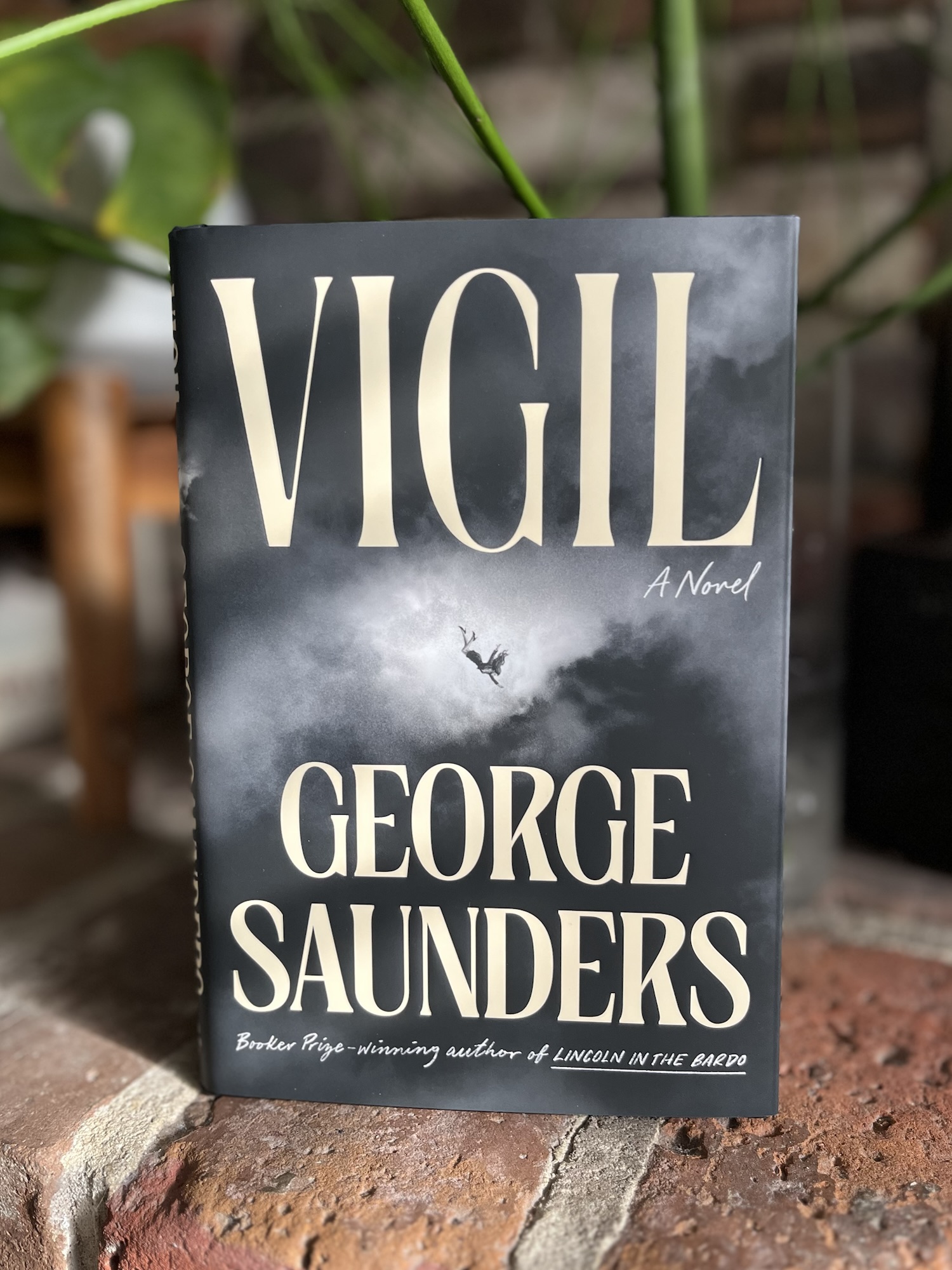

George Saunders’ latest novel Vigil is told primarily from the perspective of a ghost, Jill “Doll” Blaine, a spirit who has resisted elevation to up there in order to remain on Earth, where she guides her dying “charges” into the afterlife.

Her latest (and perhaps last) charge is one K.J. Boone, an oil tycoon dying in the “slop room” of his least favorite house. Boone spent his career denying climate science, spreading misinformation and doubt, and enriching himself from fossil fuels. He’s also a flaming asshole. He remains unrepentant as he approaches death. Gentle Jill takes compassion on the dying man, trying to “comfort” him into the next step, even as he verbally abuses her.

Jill is not the only spirit interested in Boone’s afterlife. Other ghosts pop up at the deathbed, some compassionate, some confrontational; some voices urge Boone toward self-awareness while others reinforce his denial.

We meet the most adversarial of Boone’s visiting spirits very early in the novel. As Jill arrives to comfort her “charge,” she’s interrupted by “the Frenchman,” a zany phantom who urges her not to comfort Boone but rather to “lead him, as quickly as possible, to contrition, shame, and self-loathing.” We soon learn that the Frenchman — presumably Étienne Lenoir — “had a hand in the invention of the beast.”

The “beast” here is the internal combustion engine, the great evil lurking in the background of Vigil. The Frenchman wails that his invention “poisons” the earth, air, and sea, and he spends his afterlife in a purgatory that’s one-part self-flagellation, one-part punishing avenger. It is his goal to make K.J. Boone suffer.

As Vigil toots out its plot in fragments and vignettes, we come to understand just why Boone might deserve to suffer. He conspired with other oil executives to suppress research about just how damaging carbon emissions are. Furthermore, he helped fund a right-wing ecosystem designed to manufacture constant doubt and discord. He was, in short, a willing and knowing architect of a great deal of awful shit.

Most of the obscene climate disaster takes place offstage. There are brief sketches of unstoppable fires, relentless drought, beached dolphins, ravaged forests. Famine. A climate refugee is even trotted out at one point. Etc. But Saunders focuses his camera primarily on the deathbed of the Great Man, K.J. Boone. When Boone’s degrading insults become too much — or when she’s simply distracted — Jill might confer with other spirits or drift into her own tragic past (and happy past, too). But mostly, yeah, Saunders is interested in attending to the dying old asshole.

Radical empathy has always been Saunders’ calling card, but Vigil asks too much of the reader’s patience and rewards very little in return. I suppose we are to take our narrator Jill’s charming naivety as Zen, but her mantra “Comfort. Comfort, for all else is futility” is hokey pablum.

Jill’s other mantra goes something like, you are an inevitable occurrence. All persons are inevitable; their choices are inevitable; their atrocities are inevitable. This passive worldview is a wonderful Get Out of Jail Free card, I suppose, but it’s ultimately unpersuasive. Isn’t Jill’s choice for compassion just that, a choice? Saunders’ argument — and the book does read like a sentimental screed — posits evitability with one hand while using inevitability in the other hand as a kind of cloth to wipe away real, earthly sin. It’s a parlor trick, an amusement to comfort us in dismal times.

Which is all good and yes I guess sure why not? would be fine if Vigil was, like, funny, right? Is Saunders not heir apparent to Vonnegut, to Parker, to Twain? But the humor of Vigil is not humor but rather the “idea of humor,” the shadow of humor. This novel is lifeless, bloodless, hollow.

I suppose we are meant to find some black humor in Boone’s bombastic blather and his encounters with the Frenchman and other spirits. But the premise wears thin quickly. It’s clear that Saunders wants his audience to find empathy for this imp; that he believes empathy is some kind of emotional solution. But there’s not enough of a human there to empathize with. The character is too flat, more a prop than a villain.

Vigil suffers too when compared to so many stories that mine similar territory, from A Christmas Carol to Citizen Kane to There Will Be Blood. In his NYT review of Vigil, Dwight Garner wrote that “it’s as if Clarence, the angel from It’s a Wonderful Life, came down to oblige Mr. Potter instead of George.” Garner’s characterization is fair, but Lionel Barrymore’s Potter evinces more twinkling Satanic charm than dull, horrible K.J. Boone.

Nor will Vigil fare favorably when compared to prominent climate fiction novels like The Road, The Parable of the Sower, or Oryx and Crake (let alone the under-read Moldenke novels of David Ohle). To be fair, Saunders is not attempting “cli-fi”; the earth’s imminent ecological collapse is not the soul of the novel. The souls of the novel are dying Boone and comforter Jill.

The rhetorical style of Vigil becomes especially tedious. While Jill’s voice sometimes gives over to a purposeful “elevated” style, much of the novel blips out in choppy fragments and stilted dialogue. There’s no fat on the novel, but there also isn’t much muscle. The quippiness in the end feels hollow, the voices undifferentiated, the “wisdom” merely platitudes.

The one real exception to the verbal doldrums happens very early in the novel, as the Frenchman perches on Boone’s deathbed, reading from “a tremendous stack of papers”:

The cardinal, he shouted, feeds on bits of plastic piping. In a ballroom filling with mud, chairs squeak in objection. A groggy hippo (What hippo, I wondered, why speak of hippos in this fearful place, this somber moment?) rolls yellow eyes up at a hunter seeking its ivory canines. A juvenile jaguar creeps forward, dismembers a poodle in a bright pink jacket.

Saunders seems to lovingly parody something sharper and stranger than what’s happening in Vigil, as if a lost text by André Breton or Antonin Artaud had infiltrated the novel. The feral energy and burst of color here are more dramatic than the weak tea that follows. I have more empathy for the cardinal eating plastic or the jaguar eating pets than I do for C. Koch Jay Tee Boone Pickens Hayward Dee Woods Chevron Valdez, Esq.

Saunders’ strongest work, like the stories in CivilWarLand in Bad Decline and The Tenth of December, skewered the deadened language of late capitalism while showcasing real and earned small-h heroism from the ordinary people doing their best in a system that they do not have the energy to resist.

There was always a touch of sentimentality to Saunders’ early stuff, a nice note to balance the bitter humor. But his work over the past decade has overindulged the sweet stuff. The prescient satire of a few decades ago has mellowed into a tepid drip of self-satisfied invocations to comfort, forgive, and absolve. Saunders loves his characters; he loves his readers more. And he wants, I think, to offer his readers comfort now in a miserable, miserable time. But now is not the time for comfort.