Paul Kirchner’s surreal comic strip The Bus is a looping, deadpan fugue of modern alienation and mechanical ritual, where a lone Commuter drifts through absurd, Escher-like permutations of transit life.

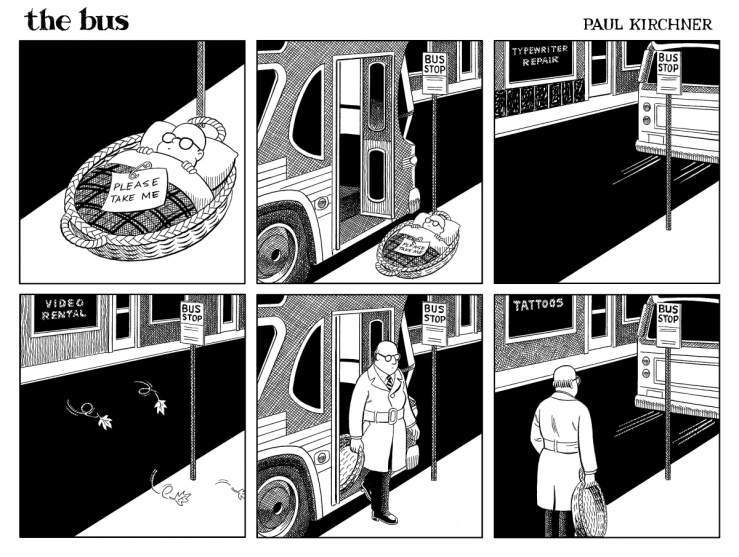

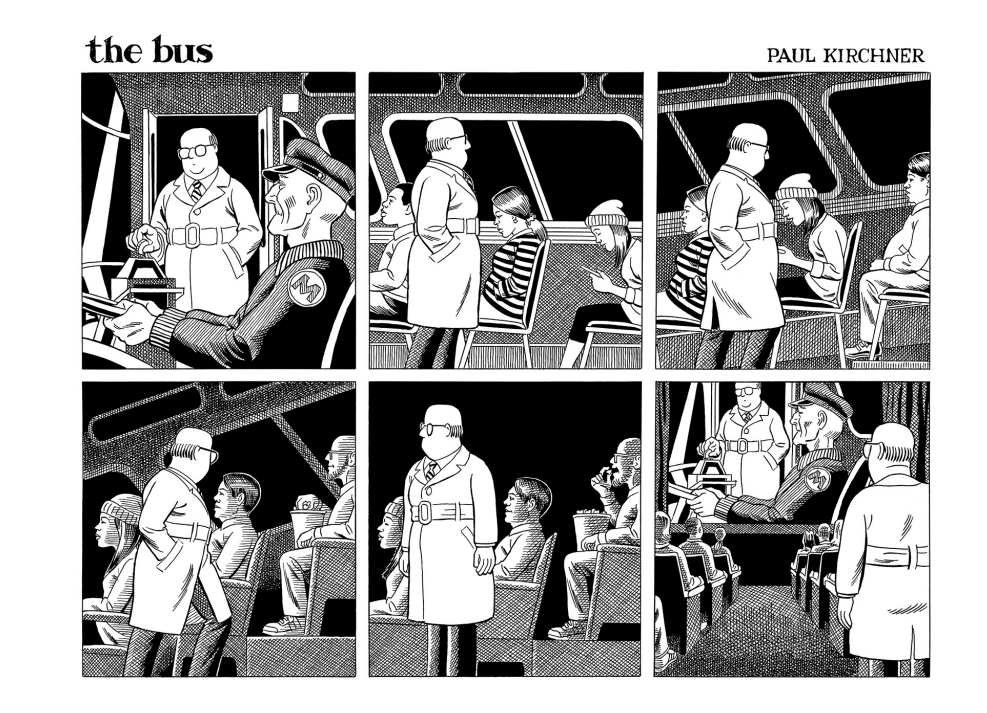

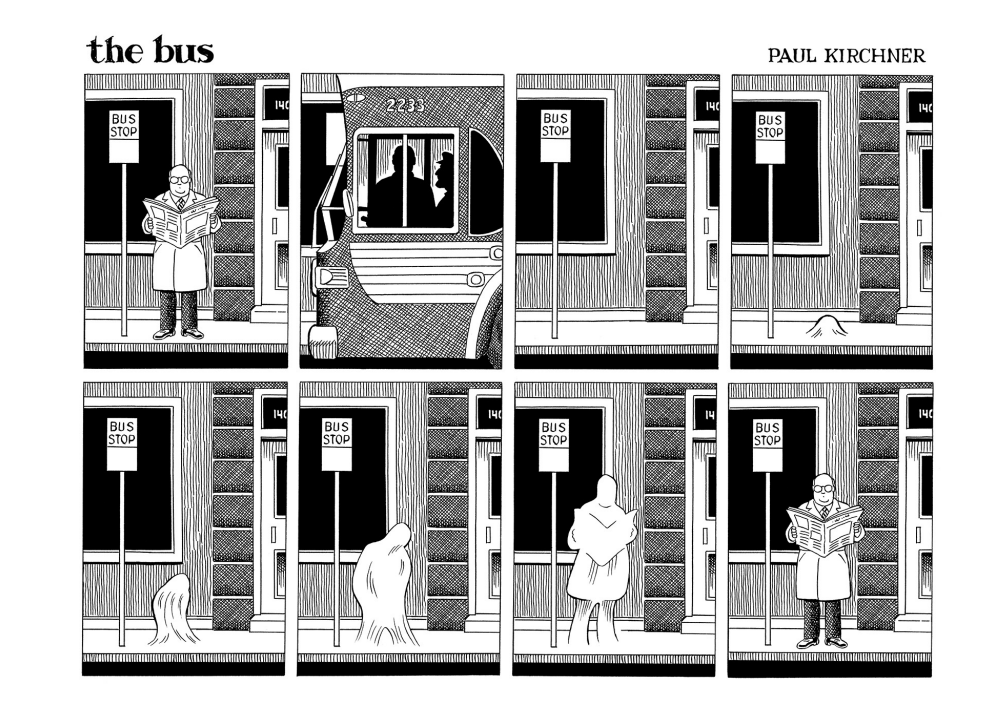

The Commuter’s foil and ferry is the titular bus (which Kirchner himself described as “demonic” in a 2015 essay in The Boston Globe); his Charon (and, really, partner) is the bus’s Driver. Each Bus strip is a double-decker one-pager rendered in precise black ink; most strips are wordless and consist of six or eight panels. Kirchner uses these constraints to conjure metaphysical gags that upend the banality of everyday existence. The previous two sentences that attempt to describe Kirchner’s formal techniques are a poor substitute for an example — so here is an example:

The strip above is the first entry in Kirchner’s new collection, The Bus 3. This strip neatly ushers us into The Bus’s charms. Old partners Commuter and Driver reunite; the bus subtly transforms into a theater; the Commuter turns to witness the loop start anew. Is there an exit? And would the Commuter want to escape the loop?

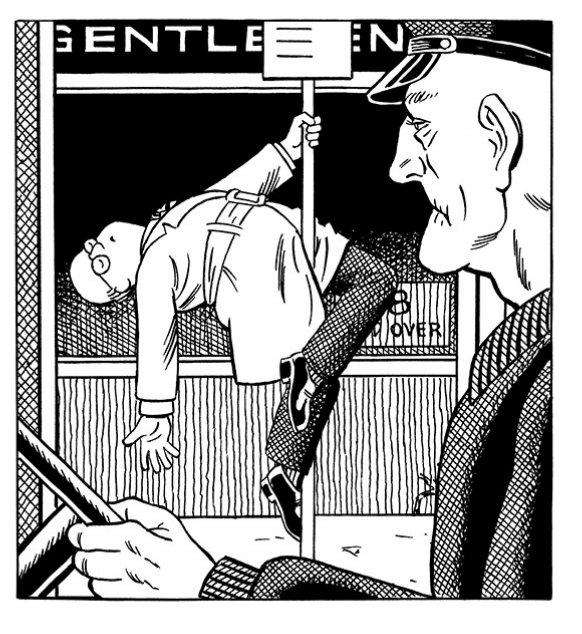

The second strip reaffirms Kirchner’s commitment to the Commuter’s eternal return. Our hapless hero is a kind of chthonic demigod, simultaneously plastic and immutable, wholly absurd:

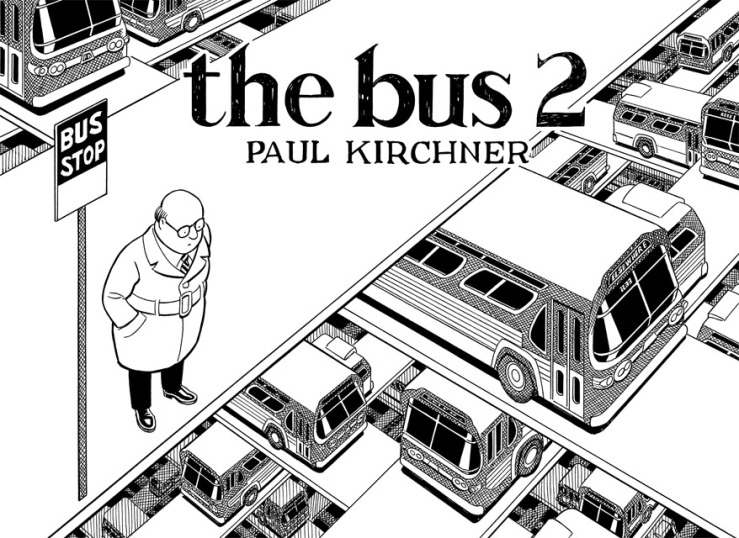

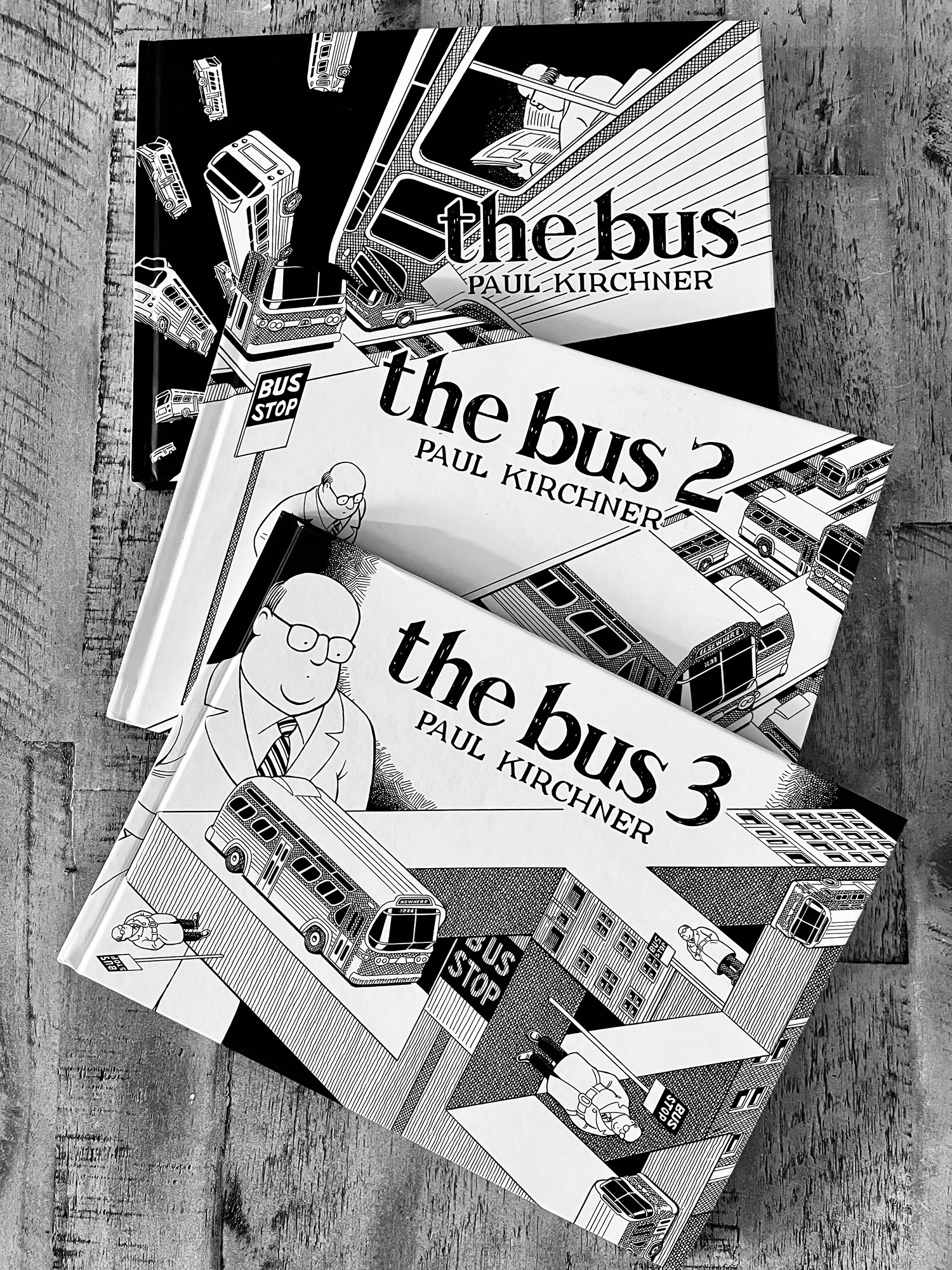

The Bus’s first route was between 1978 and 1985 in the pages of Heavy Metal magazine. French publisher Tanibis Editions republished this original run in 2012. In 2015, they published The Bus 2, a sequel of new material. In my review, I wrote that “The Bus 2, like its predecessor, is a remarkably and perhaps unexpectedly human strip.” The same is true for The Bus 3. Kirchner’s strips demonstrate that the absurdity of the modern condition, for all its dulling machinations, reaffirms humanity and the imaginative, artistic vision as a site of surreal resistance.

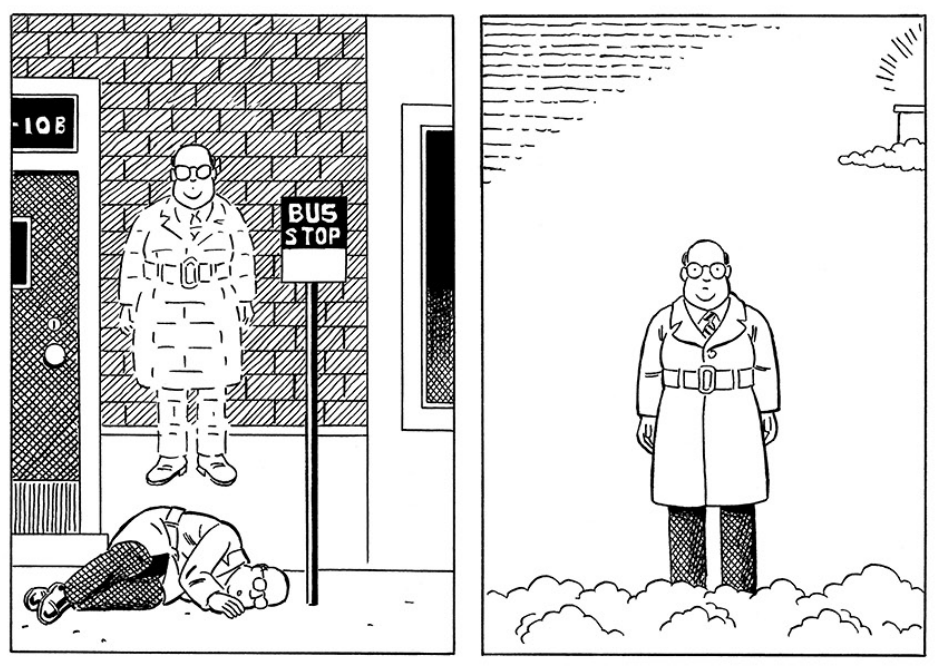

I kept The Bus 3 out on my coffee table the entire summer. I tried not to gobble up all the strips right away, but rather to read one or two a day, each page a small treat against the absurdity of the day. As I reached the end of the volume a week ago, I found myself strangely moved by the last three strips. Kirchner’s Möbius strips always send the Commuter back to his starting position. These last three pull the same move, but with a difference. In the first of the final three, the Commuter dies (waiting on the Driver, natch) and his spirit ascends. In eight speechless panels, Kirchner retells Kafka’s parable “Before the Law.”

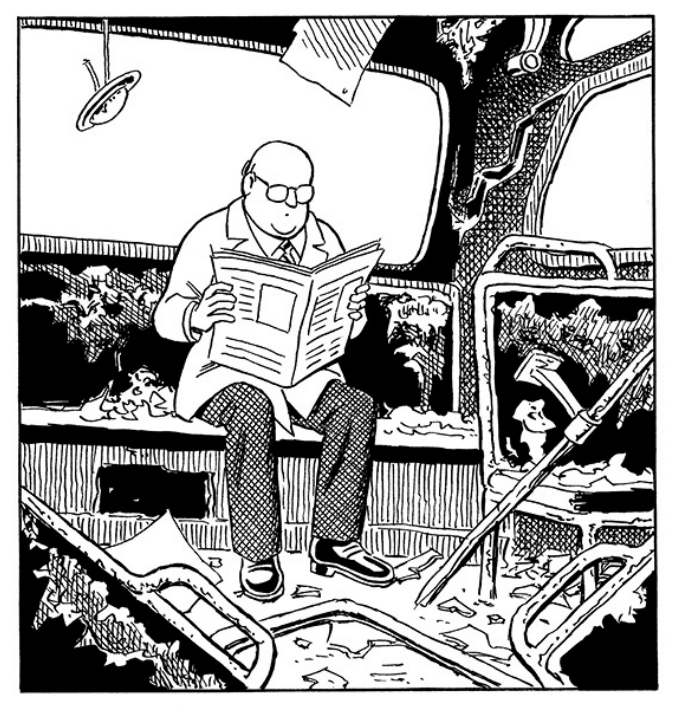

The penultimate strip, a gag on Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade balloons literally deflates the bus. The crowd has left, but the Commuter remains, stoic, waiting. And the last proper strip shows a techno-utopian future with a splendid flying bus — but our Commuter refuses to board. His neck stooped, he wanders to the outskirts of town to find the apocalyptic wreckage of his beloved broken down bus. It’s a lovely moment.

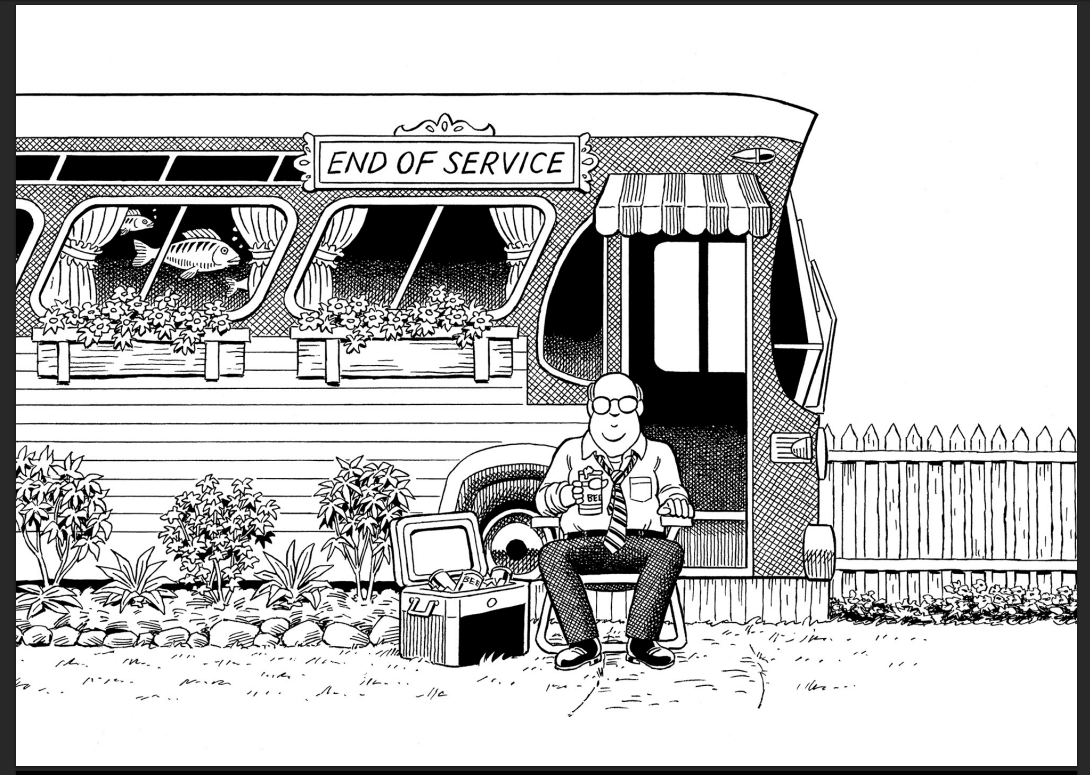

Has Kirchner retired his Commuter? Perhaps. The last page of the book shows our hero somehow looking bemused in a folding lawn chair, a cold one in his hand. He sits in front of the bus, now converted to an immobile home, scene of domestic bliss, maybe, everything tranquil and normal (just ignore the fish).

Is it really the end of service? If so, The Bus 3 offers a sweet send off for its hero. But I’ll hold out hope for one more ride. Great stuff.