Trailer for Thomas Pynchon’s new novel, Inherent Vice. Is it weird that books have trailers now? Not sure…

Tag: Inherent Vice

Inherent Vice — Thomas Pynchon

Thomas Pynchon’s latest novel, Inherent Vice is a detective-fiction genre exercise/parody set in a cartoonish, madcap circa-1970 L.A. redolent with marijuana smoke, patchouli, and paranoia. Navigating this druggy haze is private detective Doc Sportello, who, at the behest of his ex-girlfriend, searches for a missing billionaire in a plot tangled up with surfers, junkies, rock bands, New Age cults, the FBI, and a mysterious syndicate known as the Golden Fang–and that’s not even half of it. At a mere 369 pages, Inherent Vice is considerably shorter than Pynchon’s last novel Against the Day, not to mention his masterpieces Gravity’s Rainbow and Mason & Dixon, and while it might not weigh in with those novels, it does bear plenty of the same Pynchonian trademarks: a strong picaresque bent, a mix of high and low culture, plenty of pop culture references, random sex, scat jokes, characters with silly names (too many to keep track of, of course), original songs, paranoia, paranoia, paranoia, and a central irreverence that borders on disregard for the reader. And like Pynchon’s other works, Inherent Vice is a parody, a take on detective noir, but also a lovely little rip on the sort of novels that populate beaches and airport bookstores all over the world. It’s also a send-up of L.A. stories and drug novels, and really a hate/love letter to the “psychedelic 60s” (to use Sportello’s term), with much in common with Pynchon’s own Vineland (although comparisons to Elmore Leonard, Raymond Chandler, The Big Lebowski and even Chinatown wouldn’t be out of place either).

While most of Inherent Vice reverberates with zany goofiness and cheap thrills, Pynchon also uses the novel as a kind of cultural critique, proposing that modern America begins at the end of the sixties (the specter of the Manson family, the ultimate outsiders, haunts the book). The irony, of course–and undoubtedly it is purposeful irony–is that Pynchon has made similar arguments before: Gravity’s Rainbow locates the end of WWII as the beginning of modern America; the misadventures of the eponymous heroes of Mason & Dixon foreground an emerging American mythology; V. situates American place against the rise of a globally interdependent world. If Inherent Vice works in an idiom of nostalgia, it also works to undermine and puncture that nostalgia. Feeling a little melancholy, Doc remarks on the paradox underlying the sixties that “you lived in a climate of unquestioning hippie belief, pretending to trust everybody while always expecting be sold out.” In one of the novel’s most salient passages–one that has nothing to do with the plot, of course–Doc watches a music store where “in every window . . . appeared a hippie freak or a small party of hippie freaks, each listening on headphones to a different rock ‘n’ roll album and moving around at a different rhythm.” Doc’s reaction to this scene is remarkably prescient:

. . . Doc was used to outdoor concerts where thousands of people congregated to listen to music for free, and where it all got sort of blended together into a single public self, because everybody was having the same experience. But here, each person was listening in solitude, confinement and mutual silence, and some of them later at the register would actually be spending money to hear rock ‘n’ roll. It seemed to Doc like some strange kind of dues or payback. More and more lately he’d been brooding about this great collective dream that everybody was being encouraged to stay tripping around in. Only now and then would you get an unplanned glimpse at the other side.

If Doc’s tone is elegiac, the novel’s discourse works to undercut it, highlighting not so much the “great collective dream” of “a single public self,” but rather pointing out that not only was such a dream inherently false, an inherent vice, but also that this illusion came at a great price–one that people are perhaps paying even today. Doc’s take on the emerging postmodern culture is ironized elsewhere in one of the book’s more interesting subplots involving the earliest version of the internet. When Doc’s tech-savvy former mentor hips him to some info from ARPANET – “I swear it’s like acid,” he claims – Doc responds dubiously that “they outlawed acid as soon as they found out it was a channel to somethin they didn’t want us to see? Why should information be any different?” Doc’s paranoia (and if you smoked a hundred joints a day, you’d be paranoid too) might be a survival trait, but it also sometimes leads to this kind of shortsightedness.

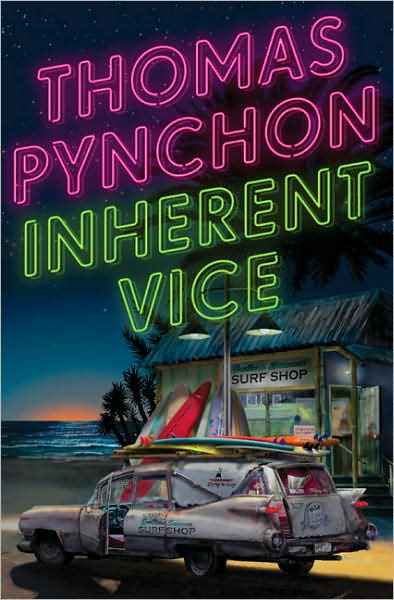

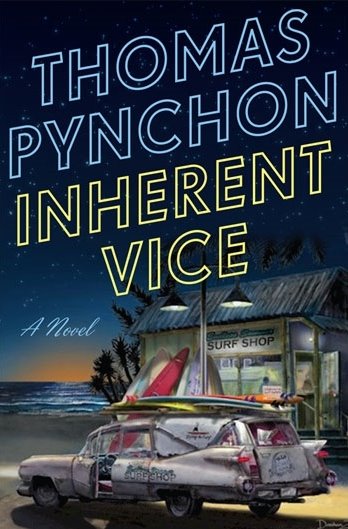

Intrinsic ironies aside, Inherent Vice can be read straightforward as a (not-so-straightforward) detective novel, living up to the promise of its cheesy cover. Honoring the genre, Pynchon writes more economically than ever, and injects plenty of action to keep up the pace in his narrative. It’s a page-turner, whatever that means, and while it’s not exactly Pynchon-lite, it’s hardly a heavy-hitter, nor does it aspire to be. At the same time, Pynchon fans are going to find plenty to dissect in this parody, and should not be disappointed with IV‘s more limited scope (don’t worry, there’s no restraint here folks–and who are we kidding, Pynchon is more or less critic-proof at this point in his career, isn’t he?). Inherent Vice is good dirty fun, a book that can be appreciated on any of several different levels, depending on “where you’re at,” as the hippies in the book like to say. Recommended.

Inherent Vice is available from Penguin August 4th, 2009.

Chris Adrian, 9/11 Lit, Thomas Pynchon, Beach Reading and More

I’m about half way through two books right now: Chris Adrian’s A Better Angel, and Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice. Pynchon’s latest novel–I’ll talk a little bit about it in a sec–comes out in hardback from Penguin August 4th. Picador will release the first trade paperback edition of Chris Adrian’s latest collection of short stories on August 3rd. I’m really digging A Better Angel so far, but before I talk about it, I just wanna shill for Picador. They put out really cool, great-looking books from really cool authors like Roberto Bolaño, J.G. Ballard, Denis Johnson, William Burroughs, and DJ Kool Herc, and they also have a sexy little imprint called BIG IDEAS//small books that puts out some killer jams. They’re also really nice about sending review copies. Shill shill shill. I’m a whore, but I’m an earnest whore.

Anyway. Back to Adrian. Just finished “The Vision of Peter Damien,” a 9/11 story set in what seems to be nineteenth century rural Ohio. Damien, and then the other children of his small rural community, catch an illness that gives them unexplained, vivid hallucinations of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center towers. Adrian works in a mode of distortion throughout most of these stories so far, repeatedly employing metaphysical disruptions as well as playing with time and setting as a way of alienating his characters from each other and the reader. Adrian uses the temporal/metaphysical disruptions of “The Vision of Peter Damien” to respond to 9/11, creating an uncanny milieu for his readers. The cognitive dissonance here reminds me of other responses to 9/11, like DeLillo’s Falling Man, David Foster Wallace’s short story “The Suffering Channel,” and even Art Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers. Actually, Wallace’s essay “The View from Mrs. Thompson’s” does a really good job of capturing all the problems of witnessing to, understanding, reacting to (etc.) spectacular disaster. Adrian’s story recapitulates the same paradoxes, injecting a motif of illness and brotherhood, contagious decay and redemption that seems to run through all of the stories collected here. I don’t have a larger comment about literature’s response to 9/11 yet, but I think that it’s fascinating to watch such stories emerge and evolve. We’re still seeing the various shapes, tropes, strategies, etc. that authors will employ to tackle (or chip at, or remark upon, or even elide) such a big historical marker. Full review of A Better Angel at the end of this month.

Far less serious is Pynchon’s new novel, Inherent Vice, a detective noir painted in day-glo psychedelic swirls. Doc Sportello, at the behest of his ex-, is searching for a missing real-estate billionaire in the dope-haze of late 60s/early 70s LA (it appears to be set in 1969, as there are repeated references to “living in the sixties and seventies”). Pynchon’s new novel is a hard-boiled detective mystery, a psychedelic caper, an LA story, a comment on the decline of idealism and the emergence of media-unreality at the end of the 60s (because we needed another story about the 60s!), and probably a shaggy dog tale. The cover has gotten some criticism for its decidedly unliterary look, and last March I called it “horrendous.” I take it back: the campy cover, with its neon shock and beach-as-pastoral-idyll is lovingly ironic, satire that does not announce itself as satire and is thus always open to a straight-reading. Just like Pynchon’s novel, the cover can be read as an homage to both Dashiell Hammett and Elmore Leonard (with a sly nod to all the Leonard ripoffs out there (glancing your way, Jimmy Buffett). As its cover suggests, this is a Pynchon book you can read breezily on a beach or airplane. Sure, it’s got the usual Pynchon trademarks–it’s overcrowded with zany, one-dimensional characters, it operates on a Looney Toons system of logic, it’s full of linguistic goofs–but it’s also incredibly easy to read (unlike, say, just about everything else Pynchon has ever written). It’s also a lot of fun. And to prove it’s a beach read, I’ll finish it this week at St.Augustine Beach, inebriated by strong margaritas and even stronger sun. Full review when I get back.

Thomas Pynchon Cover Gallery

Pynchon covers via thomaspynchon.com. The site also has a great collection of Pynchon articles and more, including the classic 1984 essay, “Is It O.K. To Be A Luddite?”

The site doesn’t have any covers for Vineland, Mason & Dixon, or Against the Day yet. Also, they skip over the horrendous cover for Pynchon’s forthcoming novel, Inherent Vice:

Also omitted: Frank Miller’s cover design for Gravity’s Rainbow: