I’d seen the diagrams, which I’ve used in the classroom for a few years now (along with Margaret Atwood’s excellent short short “Happy Endings”) but never seen this video (metaphorical hat tip to ‘klept reader ccllyyddee, who says he saw it at Curiosity Counts—cheers!).

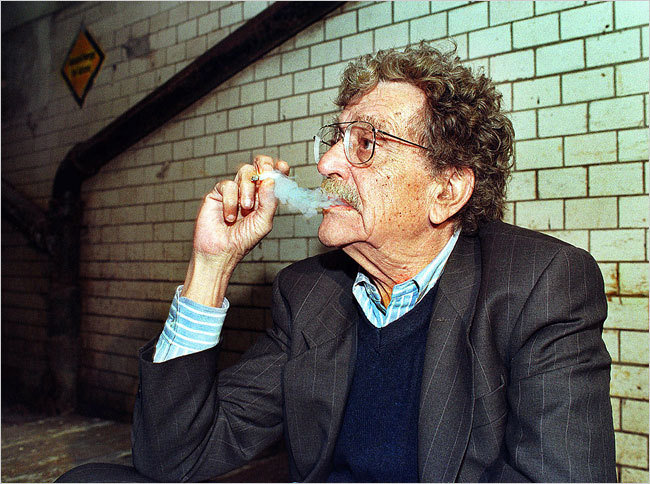

Tag: Kurt Vonnegut

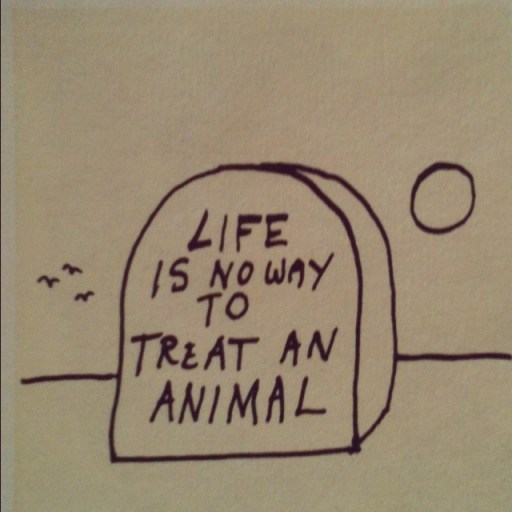

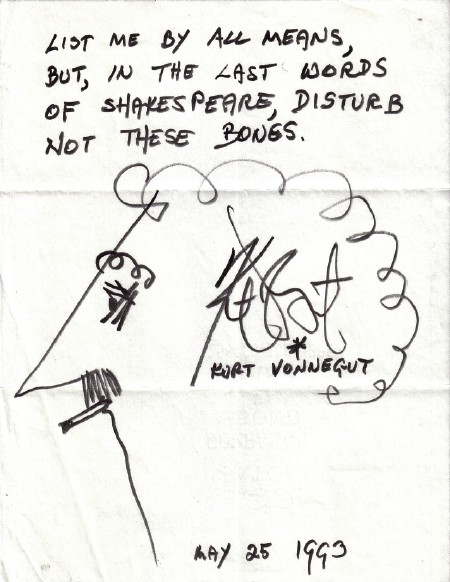

Trout’s Tomb — Kurt Vonnegut

Candide — Voltaire

I liked pretty much all of the assigned reading in high school (okay, I hated every page of Tess of the D’Ubervilles). Some of the books I left behind, metaphorically at least (Lord of the Flies, The Catcher in the Rye), and some books bewildered me, but I returned to them later, perhaps better equipped (Billy Budd; Leaves of Grass). No book stuck with me quite as much as Candide, Voltaire’s scathing satire of the Enlightenment.

I remember being unenthusiastic when my 10th grade English teacher assigned the book—it was the cover, I suppose (I stole the book and still have it), but the novel quickly absorbed all of my attention. I devoured it. It was (is) surreal and harsh and violent and funny, a prolonged attack on all of the bullshit that my 15 year old self seemed to perceive everywhere: baseless optimism, can-do spirit, and the guiding thesis that “all is for the best.” The novel gelled immediately with the Kurt Vonnegut books I was gobbling up, seemed to antecede the Beat lit I was flirting with. And while the tone of the book certainly held my attention, its structure, pacing, and plot enthralled me. I’d never read a book so willing to kill off major characters (repeatedly), to upset and displace its characters, to shift their fortunes so erratically and drastically. Not only did Voltaire repeatedly shake up the fortunes of Candide and his not-so-merry band—Pangloss, the ignorant philosopher; Cunegonde, Candide’s love interest and raison d’etre and her maid the Old Woman; Candide’s valet Cacambo; Martin, his cynical adviser—but the author seemed to play by Marvel Comics rules, bringing dead characters back to life willy nilly. While most of the novels I had been reading (both on my own and those assigned) relied on plot arcs, grand themes, and character development, Candide was (is) a bizarre series of one-damn-thing-happening-after-another. Each chapter was its own little saga, an adventure writ in miniature, with attendant rises and falls. I loved it.

I reread Candide this weekend for no real reason in particular. I’ve read it a few times since high school, but it was never assigned again—not in college, not in grad school—which may or may not be a shame. I don’t know. In any case, the book still rings my bell; indeed, for me it’s the gold standard of picaresque novels, a genre I’ve come to dearly love. Perhaps I reread it with the bad taste of John Barth’s The Sot-Weed Factor still in my mouth. As I worked my way through that bloated mess, I just kept thinking, “Okay, Voltaire did it 200 years earlier, much better and much shorter.”

Revisiting Candide for the first time in years, I find that the book is richer, meaner, and far more violent than I’d realized. Even as a callow youth, I couldn’t miss Voltaire’s attack on the Age of Reason, sustained over a slim 120 pages or so. Through the lens of more experience (both life and reading), I see that Voltaire’s project in Candide is not just to satirize the Enlightenment’s ideals of rationality and the promise of progress, but also to actively destabilize those ideals through the structure of the narrative itself. Voltaire offers us a genuine adventure narrative and punctures it repeatedly, allowing only the barest slivers of heroism—and those only come from his innocent (i.e. ignorant) title character. Candide is topsy-turvy, steeped in both irony and violence.

As a youth, the more surreal aspects of the violence appealed to me. (An auto-da-fé! Man on monkey murder! Earthquakes! Piracy! Cannibalizing buttocks!). The sexy illustrations in the edition I stole from my school helped intrigue me as well—

The self who read the book this weekend still loves a narrative steeped in violence—I can’t help it—Blood Meridian, 2666, the Marquis de Sade, Denis Johnson, etc.—but I realize now that, despite its occasional cartoonish distortions, Candide is achingly aware of the wars of Europe and the genocide underway in the New World. Voltaire by turns attacks rape and slavery, serfdom and warfare, always with a curdling contempt for the powers that be.

But perhaps I’ve gone too long though without quoting from this marvelous book, so here’s a passage from the last chapter that perhaps gives summary to Candide and his troupe’s rambling adventures: by way of context (and, honestly spoiling nothing), Candide and his friends find themselves eking out a living in boredom (although not despair) and finding war still raging around them (no shortage of heads on spikes); Candide’s Cunegonde is no longer fair but “growing uglier everyday” (and shrewish to boot!), Pangloss no longer believes that “it is the best of all worlds” they live in, yet he still preaches this philosophy, Martin finds little solace in the confirmation of his cynicism and misanthropy, and the Old Woman is withering away to death. The group finds their only entertainment comes from disputing abstract questions—

But when they were not arguing, their boredom became so oppressive that one day the old woman was driven to say, “I’d like to know which is worse: to be raped a hundred times by Negro pirates, to have one buttock cut off, to run the guantlet in the Bulgar army, to be whipped and hanged in an auto-da-fé, to be dissected, to be a galley slave—in short, to suffer all the miseries we’ve all gone through—or stay here and do nothing.

“That’s a hard question,” said Candide.

It’s amazing that over 200 years ago Voltaire posits boredom as an existential dilemma equal to violence; indeed, as its opposite. (I should stop and give credit here to Lowell Blair’s marvelous translation, which sheds much of the finicky verbiage you might find in other editions in favor of a dry, snappy deadpan, characterized in Candide’s rejoinder above). The book’s longevity might easily be attributed to its prescience, for Voltaire’s uncanny ability to swiftly and expertly assassinate all the rhetorical and philosophical veils by which civilization hides its inclinations to predation and straight up evil. But it’s more than that. Pointing out that humanity is ugly and nasty and hypocritical is perhaps easy enough, but few writers can do this in a way that is as entertaining as what we find in Candide. Beyond that entertainment factor, Candide earns its famous conclusion: “We must cultivate our garden,” young (or not so young now) Candide avers, a simple, declarative statement, one that points to the book’s grand thesis: we must work to overcome poverty, ignorance, and, yes, boredom. I’m sure, gentle, well-read reader, that you’ve read Candide before, but I’d humbly suggest to read it again.

Kurt Vonnegut Grades His Books

Kurt Vonnegut Talks Cat’s Cradle

“I Had Made a Bad Trade” — Kurt Vonnegut on Quitting (and Resuming) Smoking

From The Paris Review interview archive: Kurt Vonnegut discusses quitting smoking and then starting again and then quitting and then stating again–

INTERVIEWER: Have you ever stopped smoking?

VONNEGUT: Twice. Once I did it cold turkey, and turned into Santa Claus. I became roly-poly. I was approaching two hundred and fifty pounds. I stopped for almost a year, and then the University of Hawaii brought me to Oahu to speak. I was drinking out of a coconut on the roof of the Ili Kai one night, and all I had to do to complete the ring of my happiness was to smoke a cigarette. Which I did.

INTERVIEWER: The second time?

VONNEGUT: Very recently—last year. I paid Smokenders a hundred and fifty dollars to help me quit, over a period of six weeks. It was exactly as they had promised—easy and instructive. I won my graduation certificate and recognition pin. The only trouble was that I had also gone insane. I was supremely happy and proud, but those around me found me unbearably opinionated and abrupt and boisterous. Also: I had stopped writing. I didn’t even write letters anymore. I had made a bad trade, evidently. So I started smoking again. As the National Association of Manufacturers used to say, “There’s no such thing as a free lunch.”

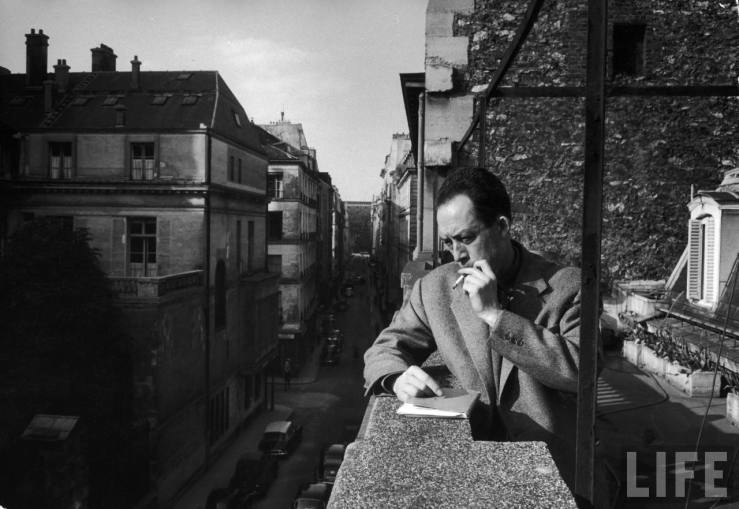

Smoking Makes You Look Cool

Word of the Day: Sillograph

From the OED:

“A writer of satires or lampoons; applied to Timon of Phlius (268 BC).

1845 LEWES Hist. Philos. I. 77 His state of mind is finely described by Timon the sillograph. 1849 GROTE Hist. Greece II. xxxvii. IV. 526 The sillograph Timon of the third century B.C.

So sillographer, sillographist.

1656 BLOUNT Glossogr., Sillographer, a writer of scoffs, taunts and revilings; such was Timon. 1775 ASH, Sillographist. 1845 Encycl. Metrop. X. 393/1 Menippus indeed, in common with the Sillographers, seems to have introduced much more parody than even the earliest Roman Satirists.”

Famous sillographers include:

Timon of Philius (as noted above)

Kurt Vonnegut Reconsidered

Kurt Vonnegut died a year ago today. Vonnegut’s death has left neither a cultural vacuum nor a pining after another great work now never to be. And why should it? He was pretty old–84–and he’d written a relatively substantial collection of novels, plays, essays, and short stories. And admittedly, he hadn’t written a truly great book in decades. Like Bob Dylan, Vonnegut produced his greatest work in the 1960s: Mother Night, Cat’s Cradle, God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, and, of course, Slaughterhouse-Five (even 1968’s short story collection Welcome to the Monkey House–a book I proudly admit I stole from my 10th grade English teacher–is superior to Vonnegut’s later work). Yet there’s still something about his death that makes me feel a little melancholy, even now–not sad, per se, but rather–and it sounds corny–like something is missing.

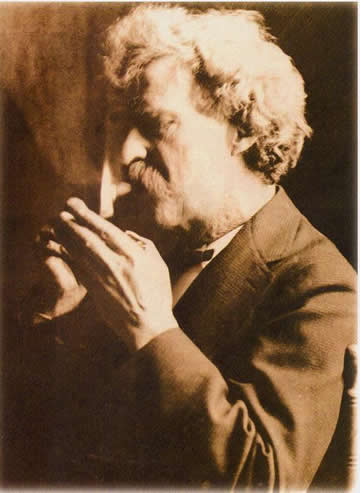

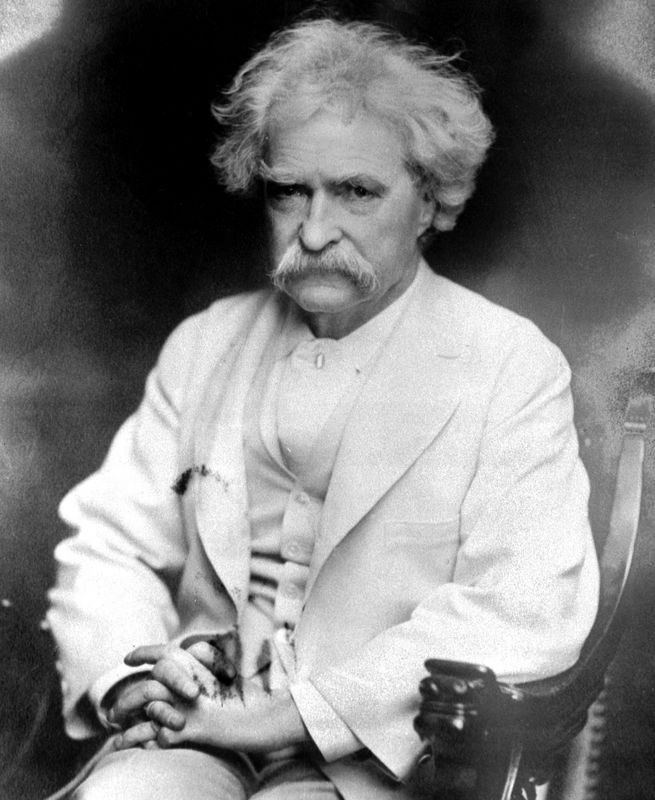

See, I learned to read by reading Vonnegut. Sure, I knew how to read before I read Cat’s Cradle, but, beyond Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and a number of classic adventure books by authors like Edgar Rice Burroughs and Mark Twain, Vonnegut was the first “literary” author I was exposed to. I learned irony. I learned detached pessimism. I was exposed to a writer who knew how to explode genre convention. And, in a short period–roughly from the ages of 12 to 16–I read everything that Vonnegut had written. Then I dismissed him as a “lesser” writer, and moved on, until I was required to re-read Slaughterhouse-Five in college. I’d forgotten how good it was. I re-read Cat’s Cradle, my first and favorite (to this day) Vonnegut novel. Again, great. I then picked up Vonnegut’s final novel, 1997’s Timequake, a shambolic wreck of semi-autobiography that is at turns drastically pessimistic, utterly depressive, and hilariously cynical. It’s really a terrible book, to be honest, but taken as a final statement, I think it works. In any case, after college I managed to get over the silly embarrassment I felt for my love of Vonnegut, an author often relegated to the second or even third tier of American letters, or, even worse, a personality reviled in the press (watch Fox News’s scandalous obituary. Or, if you prefer watching something positive, watch Vonnegut on The Daily Show.)

I suppose, when I say that Vonnegut’s death presents an absence, a feeling of something missing, I really mean to say that it marks me, it ages me: it makes me feel old. After all, we measure our own lives in part against the deaths of others, particularly against the deaths of the famous and celebrated. Vonnegut preceded me; his novels were there, waiting for me, and I was grateful. I read all of them–all of them–I don’t know if I can say that of another author (except maybe Salinger, and I don’t think that counts). But I still haven’t read A Man Without a Country, his 2005 collection of essays, and I haven’t read the posthumously published short story collection, Armageddon in Retrospect, which came out just the other week. It makes me happy to know that there’s something out there of his that I haven’t yet touched, that I can read for the first time as an adult, and not a teenager. I don’t know why I should feel this way, but I do. So it goes.

Vonnegut plays himself in an classic film:

A Unique Brand of Despondent Leftism?

In case you need another reason to hate Fox News:

I find it amazing that despite Vonnegut’s lifetime of art and achievement, the schmuck-reporter takes the time to mention that the celebrated writer “failed at suicide 23 years ago” in a two minute segment.

God Bless You, Mr. Vonnegut

Like many of you I’m sure, I cut my literary teeth on Kurt Vonnegut, who died early this morning. My dad gave me three of Vonnegut’s books–Breakfast of Champions, Slaughterhouse Five, and The Sirens of Titan–when I was about eleven or twelve. It’s a cliché, but these books really did change my life forever. In the next couple of years, I devoured everything Vonnegut wrote. My favorite book of his was and is Cat’s Cradle, which I think surpasses both Mother Night and Slaughterhouse Five as his most important work. As I grew older, I began to reject Vonnegut, to see him as not as serious or profound as the authors I was reading. His later books like Hocus Pocus and the truly-lamentable Timequake didn’t help either. Nevertheless, I read them as soon as they came out in paperback. I had to. I had to read everything he wrote. Celebrate Vonnegut’s life by reading one of his books, and remember what got you into reading in the first place.