Last year, Saturday Night Live ran an unfunny parody of an infamous viral video. SNL sought to mock the 2009 Gathering of the Juggalos Infomercial which advertised the tenth anniversary spectacular for that venerable event. The Gathering of the Juggalos is an annual outdoor music and culture festival initiated by and starring Insane Clown Posse. The best way to (try to) understand it is to watch the infomercial. You can watch the infomercial and SNL‘s parody at Current, which I suggest you do now. Done? Okay.

SNL‘s parody is not funny, it is merely observational; that is to say, it doesn’t ever approach satire. It is unfunny mimicry of something far funnier. There is no topping the riotous authenticity of the thing in itself. The original Juggalo infomercial’s joyful exuberance resists SNL‘s ironic aims–it can’t really be satirized. It is beyond kitsch, and eventually even schadenfreude. It does not seem real. Can the ICP enterprise be in earnest, though? Take their new video “Miracles,” for example–are these guys for real? Take a few minutes to watch this. I insist. (NB: Lyrics NSFW).

The video, apparently directed by Lisa Frank, communicates a sincere adoration and sense of wonder and possibility in a world of shit that’ll shock your eyelids, like: long neck giraffes, pet cats and dogs, fucking shooting stars and fucking rainbows, UFOs, crows, ghosts, moms, kids . . . you know, pure motherfucking magic. There’s a paradox in Shaggy 2 Dope and Violent J in full malevolent get-up vamping in front of rainbows and stars and expressing anger at scientists who would dare to explain how fucking magnets work. Even more perplexing, earlier this year, ICP released the trailer for their Western film, Big Money Rustlas the deadly tale of debauchery, hedonism, and family love set in a small town of Mudbug. Again, I insist you watch the trailer. (NB: Language NSFW).

How might one go about satirizing that? It already seems framed as a parody of a parody. It’s anti-satiric. It self-ironizes. But again: How sincere are ICP?

Thomas Morton’s “In the Land of the Juggalos” (Vice magazine), the authoritative, in-depth investigation into the 2007 Gathering, reveals a close-knit culture of rejects reveling in “the worst aspects of goth, punk, gangsta rap, rave, nu-metal, and real metal to create a sub-culture so universally repulsive as to forestall any attempts at outside involvement.” Equally good, and more immediately accessible is Derek Erdman’s photo essay documenting the 2009 Gathering–the one advertised in the promo video. His marvelous, grotesque photos show a sincere audience, eager members of the Psychopathic Records “family.” Take a few minutes to suck it all in. These people are serious in their Juggaloness. But again, what of ICP themselves? They can’t be art-pranksters or scammers, can they? They are clearly serious about ICP as a money-making enterprise but what about as a form of art or cultural commentary? Can they be serious about the absurd sentimental content of “Miracles” or their woefully dumb Western film? Are they for real?

There is a radical authenticity about ICP’s project. It’s an autochthonous monster engendering a legion of mutant fans. Yet it also seems potently aware of its position. ICP/Juggalo culture strikes me as a form of ritual theater assuring a sense of belonging and even meaning in life to a group of people who choose to see themselves as outcast or othered. It is inconceivable to suggest that they are wholly or even partly unaware of how others see them; indeed, awareness of how others perceive them is exactly what gives meaning to being a down-assed ninja, a true Juggalo. They see you seeing them (seeing you seeing them).

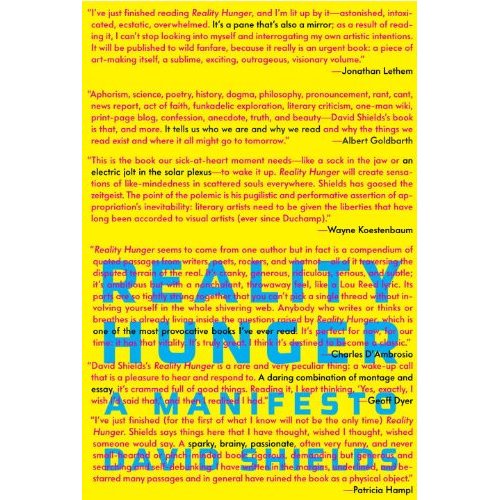

Hence a condition of post-postmodernity, of a ludic and labyrinthine culture that produces subcultures resistant to irony, to parody, to the defenses of Modernism and the techniques of postmodernism. If we contrast the gap between SNL’s parody and the real thing, we might be led to what I think David Shields is trying to describe in his book Reality Hunger, a situation where the narrative techniques of modernity (and their counterparts in postmodernism) are no longer tenable forms of discourse and analysis in an increasingly technologically mediated world.

Experiment: Imagine that you wish to satirize (or parody) Walmart. Envision the details and observations you will use to mock the behemoth, its customers, its gross place in America. Then go to a Walmart. You are trumped. Hyperbole and irony are beyond you. There is no way to top the thing in itself. You are left merely with a set of observations, not insights. An ironic viewpoint does not cease to exist, but it can’t be supported via the traditional methods of Modernism or postmodernism. Contrast South Park‘s Walmart satire with the website People of Walmart. The former attempts to justify an ironic viewpoint through the logic of satire and mimesis. The latter is an ironic viewpoint of an objective reality. It’s not even parody. It’s “real.”

And this is why SNL’s Juggalo spoof signals the limits of parody and cultural parody’s satirical, mimetic aims. Like People of Walmart, it’s just an ironic viewpoint of an objective reality. The postmodern distortions of ICP (their clown paint, their mythos, their argot, their identities, their Faygo) and the surreal, trashy carnival of the Gathering present an objective reality radically open to a host of ironic semiotic machinations delivered in an earnestness that trumps satire. ICP have already done the work for you. Their world hosts ironic oppositions; their nihilistic anthem “Fuck the World” directly contradicts the sugary magical wonder of “Miracles.” The weird identity-symbiosis they share with their fans is wholly defined by radical otherness and alienation. If you take the time to wade through comment boards on ICP related videos, news, and articles (you shouldn’t do that, btw, dear reader), you’ll find a fierce hatred of Juggalos–a fierce hatred that paradoxically defines and confers identity upon the Juggalo. This is a priori irony. ICP’s aesthetic identity resists mockery, renders mockery moot. A recent internet video, “The Juggalo News,” attempts to satirize Juggalo culture. It’s mildly amusing but ultimately offers no insight. It’s failed satire.

Far better to dispense with pointless parody and enjoy ICP’s works for whatever they are. Re-watch “Miracles.” Around 1:09 or so Violent J raps: “I fed a fish to a pelican at Frisco bay / It tried to eat my cell phone” and Shaggy responds: “He ran away,” kicking a leg back and thrusting an arm forward in a pose evocative of Superman to illustrate the action of his bosom companion’s narrative. This is more precious than gold, Shaggy’s gesture, a miracle in “Miracles,” and I will take it as an earnest gift. ICP has brought me some measure of joy, and yes, tears (of laughter) in my time, so I do thank them.