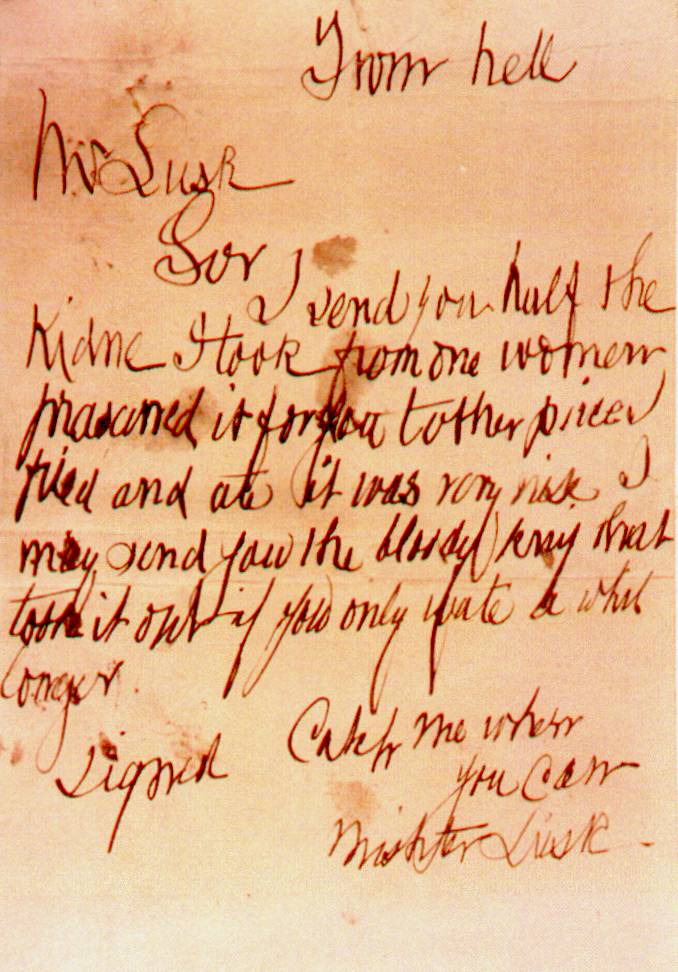

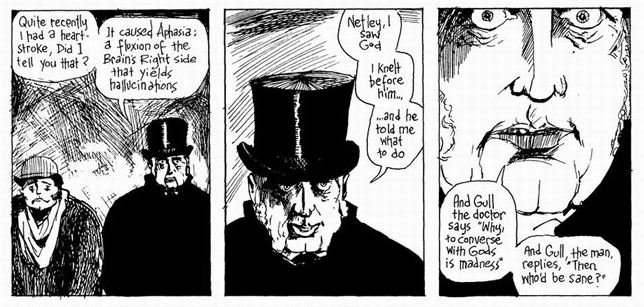

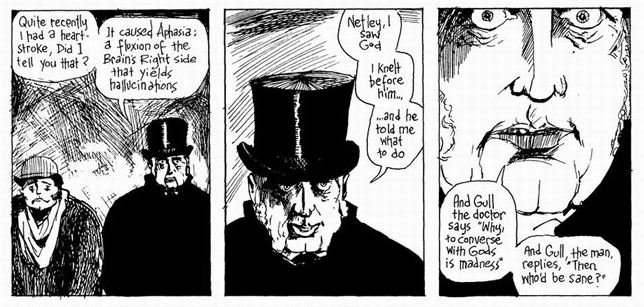

From Hell, Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s epic revision of the Jack the Ripper murders, posits Sir William Gull, a physician to Queen Victoria, as the orchestrator of the Jack the Ripper murders that terrified Londoners at the end of the 19th century. The murders initially arise out of the need to cover up the knowledge of the existence of an illegitimate son begat by foolish Prince Albert, Victoria’s grandson. However, for Gull the murders represent much more–they are part of the continued forces of “masculine rationality” that will constrain “lunar female power.” Gull is a high-level Mason; during a stroke, he experiences a vision of the Masonic god Jahbulon, one which prompts him to his “great work”–namely, the murders that will reify masculine dominance.

One of the standout chapters in the book is Gull’s tour of London, with his hapless (and witless) sidekick Netley. In a trip that weds geography, religion, politics, and mythology, Gull riffs on a barbaric, hermetic history of London, revealing the gritty city as an ongoing site of conflict between paganism and orthodoxy, artistic lunacy and scientific rationality, female and male, left brain and right brain. The tour ends with a plan to commit the first murder. From there, the book picks up the story of Frederick Abberline, the Scotland Yard inspector charged with solving the murders. Of course, the murders are unsolvable, as the hierarchy of London–from the Queen down to the head of police–are well aware of who the (government-commissioned) murderer is. The police procedural aspects of the plot are fascinating and offer a balanced contrast with Gull’s mystical visions–visions that culminate in a climax of a sort of time-travel, in which Gull not only sees London at the end of the twentieth century, but also receives a guarantee that his murder plot has had its intended effect. From Hell takes many of its cues from the idea that history is shaped not by random events, but rather by tragic conspiracies that force people to willingly give up freedom to a “rational” authority. The book points repeatedly to the 1811 Ratcliffe Highway murders, which led directly to the world’s first modern police force. In our own time, if we’re open to conspiracy theories, we might find the same pattern in the 21st century responses to terrorism (Patriot Act, anyone?).

Although From Hell features moments of supernatural horror in Gull’s mysticism, it is the book’s grimy realism that is far more terrifying. London in the late 1880s is no place you want to be, especially if you are poor, especially if you are a woman. The city is its own character, a labyrinth larded with ancient secrets the inhabitants of which cannot hope to plumb. Despite the nineteenth century’s claims for enlightenment and rationality, this London is bizarrely cruel and deeply unfair. Campbell’s style evokes this London and its denizens with a surreal brilliance; his dark inks are by turns exacting and then erratic, concentrated and purposeful and then wild and severe. The art is somehow both rich and stark, like the coal-begrimed London it replicates. Although Moore has much to say, he allows Campbell’s art to forward the plot whenever possible. Moore is erudite and fascinating; even when one of his characters is lecturing us, it’s a lecture we want to hear. His ear for dialog and tone lends great sympathy to each of the characters, especially the unfortunate women who must turn to prostitution to earn their “doss” money. And while Abberline’s frustrations at having to solve a crime that no higher-ups want solve make him the hero of this story, Gull’s mystic madness makes him the narrative’s dominant figure. Rereading this time, I realized there is no character he reminds me of as much as Judge Holden from Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. I’m also reading Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent now, a book that dovetails neatly with From Hell, both in its time and setting, but also in its exploration of social unrest and duplicitous authority. Both novels feature detectives fighting a complacent system, and both novels feature a working class that threatens to erupt in socialist or anarchist rebellion.

From Hell is a fantastic starting place for anyone interested in Moore’s work, more self-contained than his comics that reimagine superhero myths, like Watchmen or Swamp Thing, and more satisfying and fully achieved than Promethea or V Is for Vendetta. Be forewarned that it is a graphic graphic novel, although I do not believe its violence is gratuitous or purposeless. Indeed, From Hell aspires to remark upon the futility and ugliness of cyclical violence, and it does so with wisdom and verve. Highly recommended.

[Ed. note: We ran a version of this review last year; we run it again in celebration of Halloween].