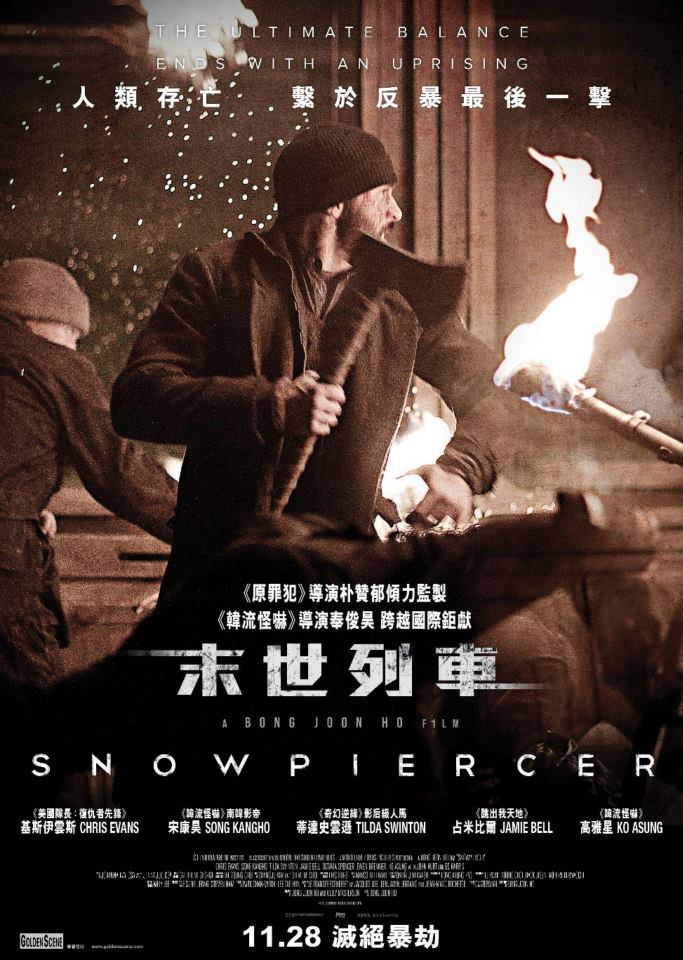

1. Snowpiercer, 2013, directed by Bong Joon Ho and produced by Park Chan Wook, is a sci-fi dystopian set on a mega-train, where the vestiges of humanity survive, protected from the new ice age outside. The plot involves the third-class passengers’ revolt against the elites who enjoy a privileged life at the head of the train. Etc.

2. You’ve seen this movie before, read this book before. You’ve played this video game.

3. Metropolis, Soylent Green, 12 Monkeys, Half-Life 2, The Time Machine, the MaddAddam trilogy, Children of Men, BioShock, Zardoz, Logan’s Run, Brave New World, Brazil, The City of Lost Children, Bad Dudes, Die Hard, The Polar Express, etc.

4. Points 2 and 3 are lazy writing, and Snowpiercer deserves better. Although the film is not especially original, it does have a clear point of view, its own aesthetics, and an engaging, energetic rhythm, powered by strong (if purposefully cartoonish) performances from its cast.

5. Snowpiercer is essentially structured like a video game. The heroes, a rebel alliance led by Chris Evans (Captain America, looking like The Edge from U2 for half the film), clear each train car—each game board—before moving on to the next challenge. An early standout scene involves a fight with a band of ninjas who for some reason ritually slaughter a fish before battle (the scene echoes the famous hammer hallway fight in Old Boy, a film directed by Snowpiercer producer Chan Wook Park).

6. The simple narrative structure of Snowpiercer allows the filmmakers to highlight the plot’s allegorical dimension. Highlight is the wrong verb: What I mean to say is hammer. Snowpiercer is not especially subtle in its critique of capitalism, with the engine that powers the train as a metaphor for capitalism itself—the engine determines the form of the train which in turn shapes the form of the society that must live in the train.

7. At Jacobin, Peter Frase offers a strong argument that the film challenges the entire system of capitalism and ultimately advocates transcendence of the system—not internal revolution.

8. While I think Frase’s essay offers a compelling analysis, I think that he simply wants the film to be better than it is. Snowpiercer, despite an apparent subversive streak, is still a Hollywoodish spectacle of violence and noise. It cannot transcend its own tropes (it can’t even revolutionize them). The vision of transcendence it offers is a rhetorical trick; not only that, it’s a stale trick, one that we can find at the end of any number of dystopian fictions: The exit door, the escape hatch, the way out.

9. I want to talk about that exit door—the end of the film: so major spoilers ahead. Continue reading “Snowpiercer Riff” →