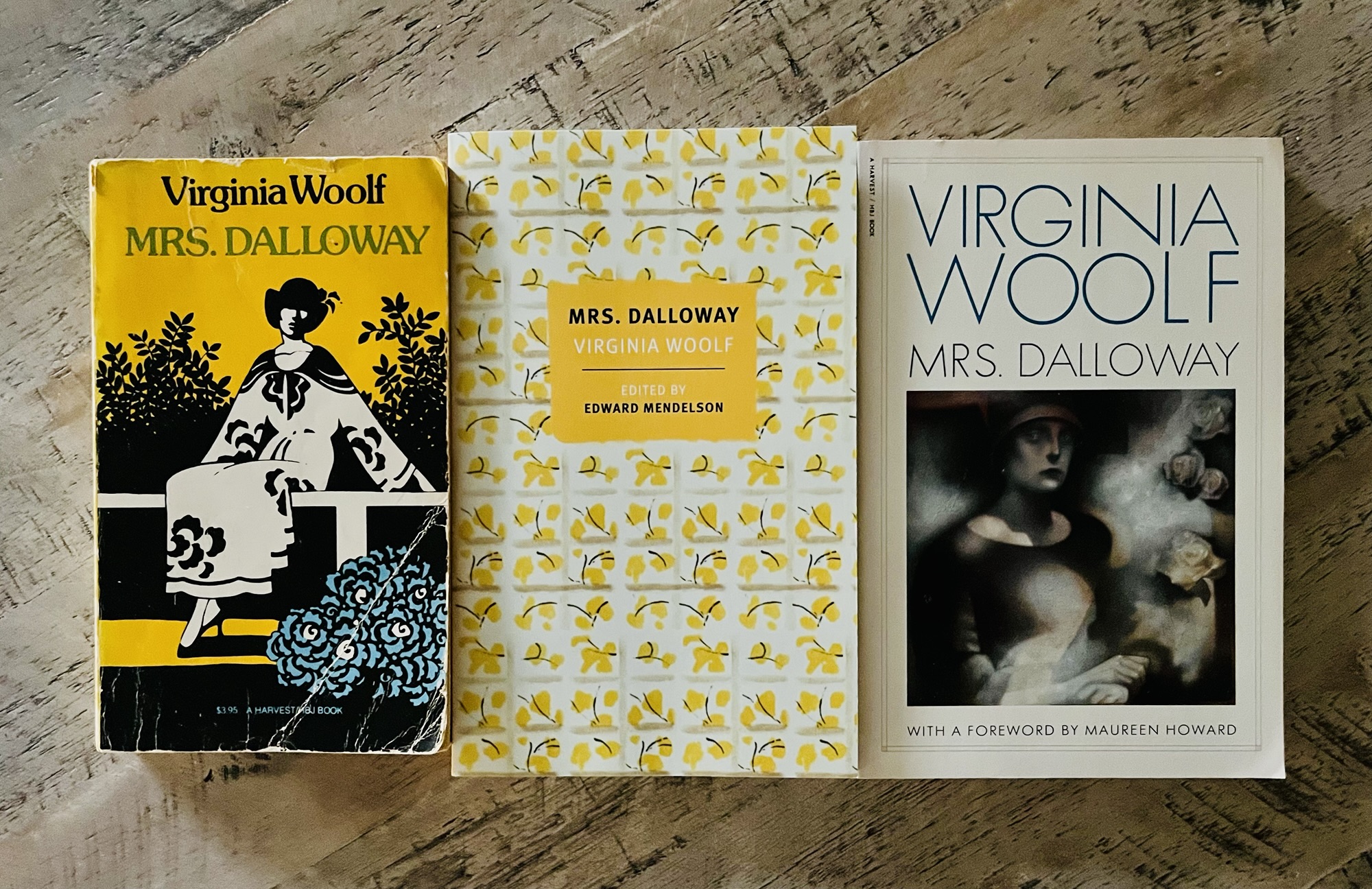

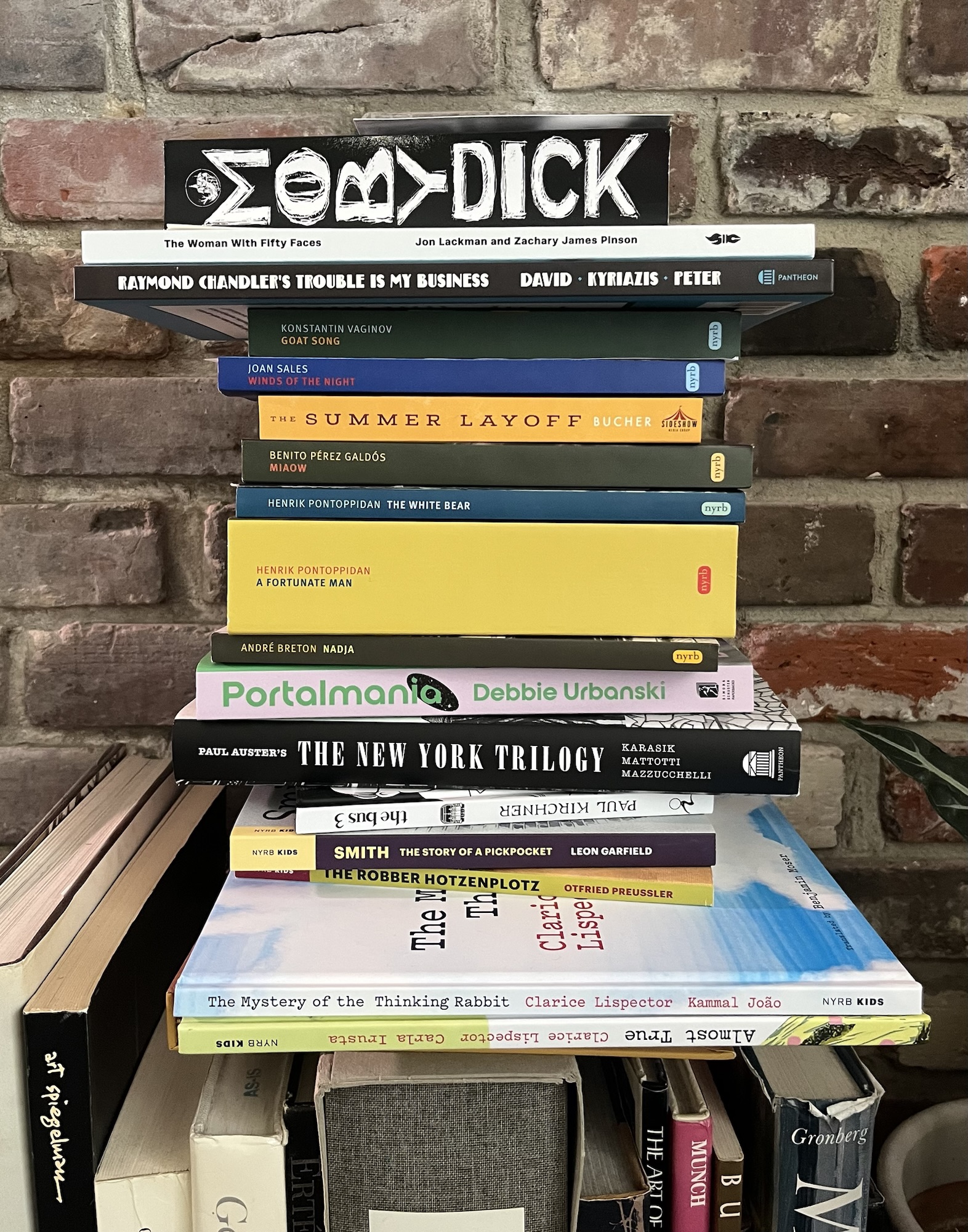

The afternoon my best friend died, three review titles arrived at Biblioklept World Headquarters. That was the first Monday in May 2025.

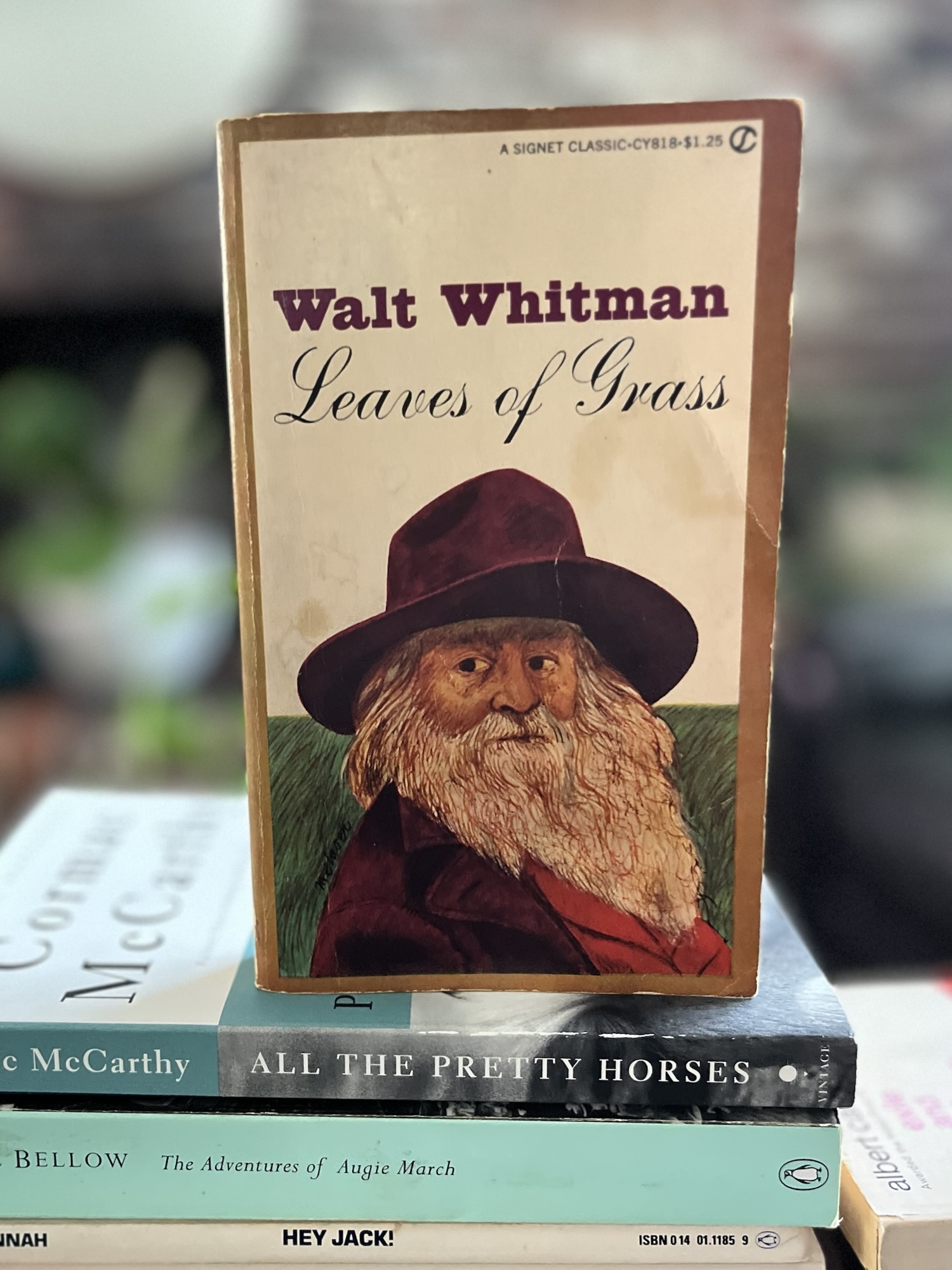

The next day, the first Tuesday in May 2025, a lovely new copy of Moby-Dick arrived, designed and illustrated by my old internet friend Dmitry Samarov. I was regularly breaking down into a kind of horrified shaking disbelief throughout this day. My best friend read Moby-Dick before I did. He told me it was funny and that I could read it, “No problem man.” He loaned me his copy of Pierre when I had to read it in grad school. I never gave it back.

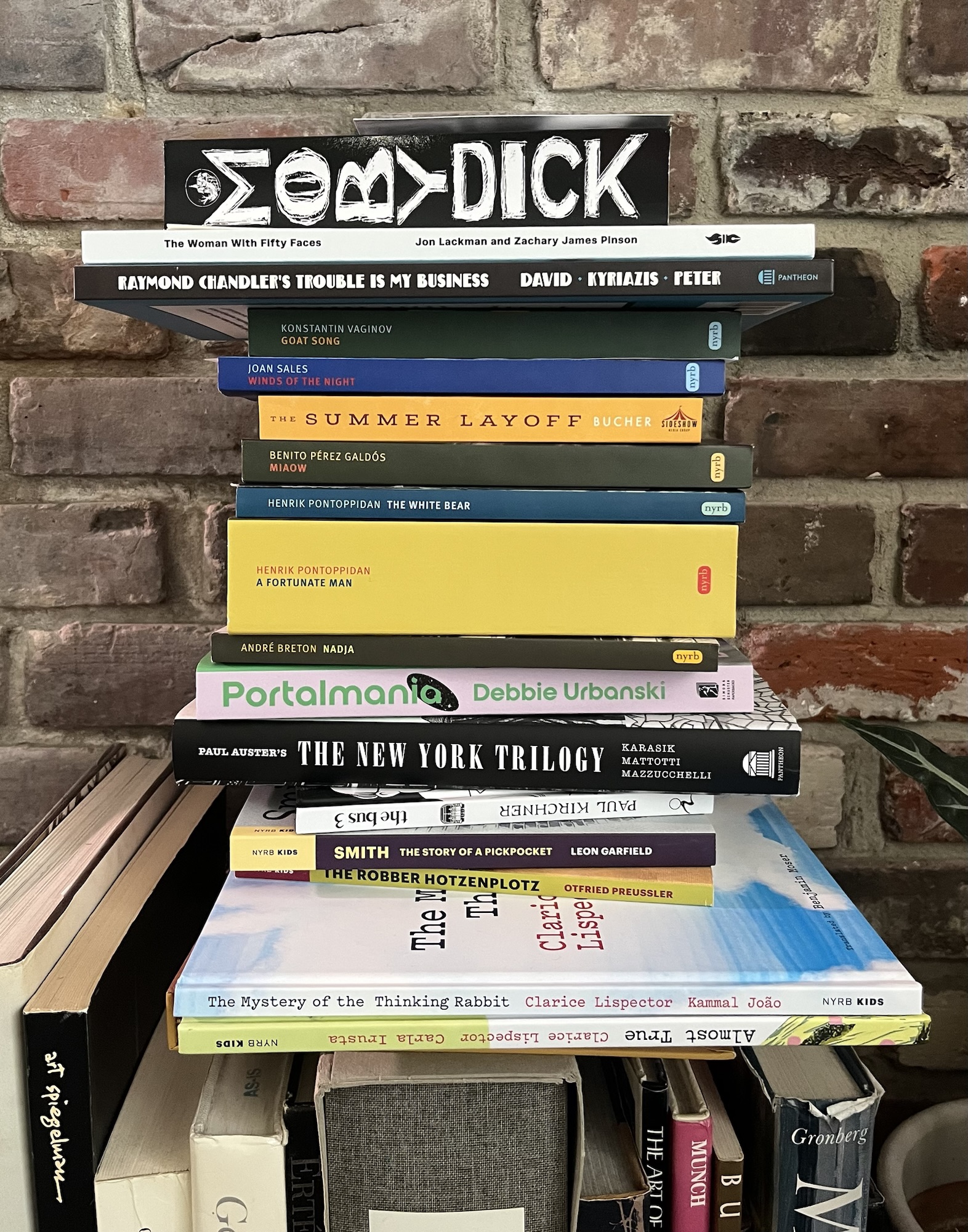

On Wednesday–do I need to clue you in that this was the first Wednesday of May 2025? I seem to have lost my sense of time and scale this month, untethered from the Spring semester, which ended right as May began, unencumbered from any normalizing duty other than fatherhood and husbandry and just generally trying to be a good citizen–also generally numb in my nascent grief to the daily horrors of the what we call news or current events or what-have-you–but, yeah, I seem to have lost some days here… (maybe they’ve been colonized by the “Asiatick Pygmies” of Thomas Pynchon’s Against the Day, who colonized the “eleven missing days” of September 1752)… So well anyway on this first Wednesday of May 2025 the growing book pile took a silly turn, with the arrival of a massive book and a not-so-massive book, both by Henrik Pontoppidan. Other books arrived too. It’s the Spring catalog, or maybe the Summer catalog, I guess.

I managed to write something about my friend on Wednesday. I simply had to.

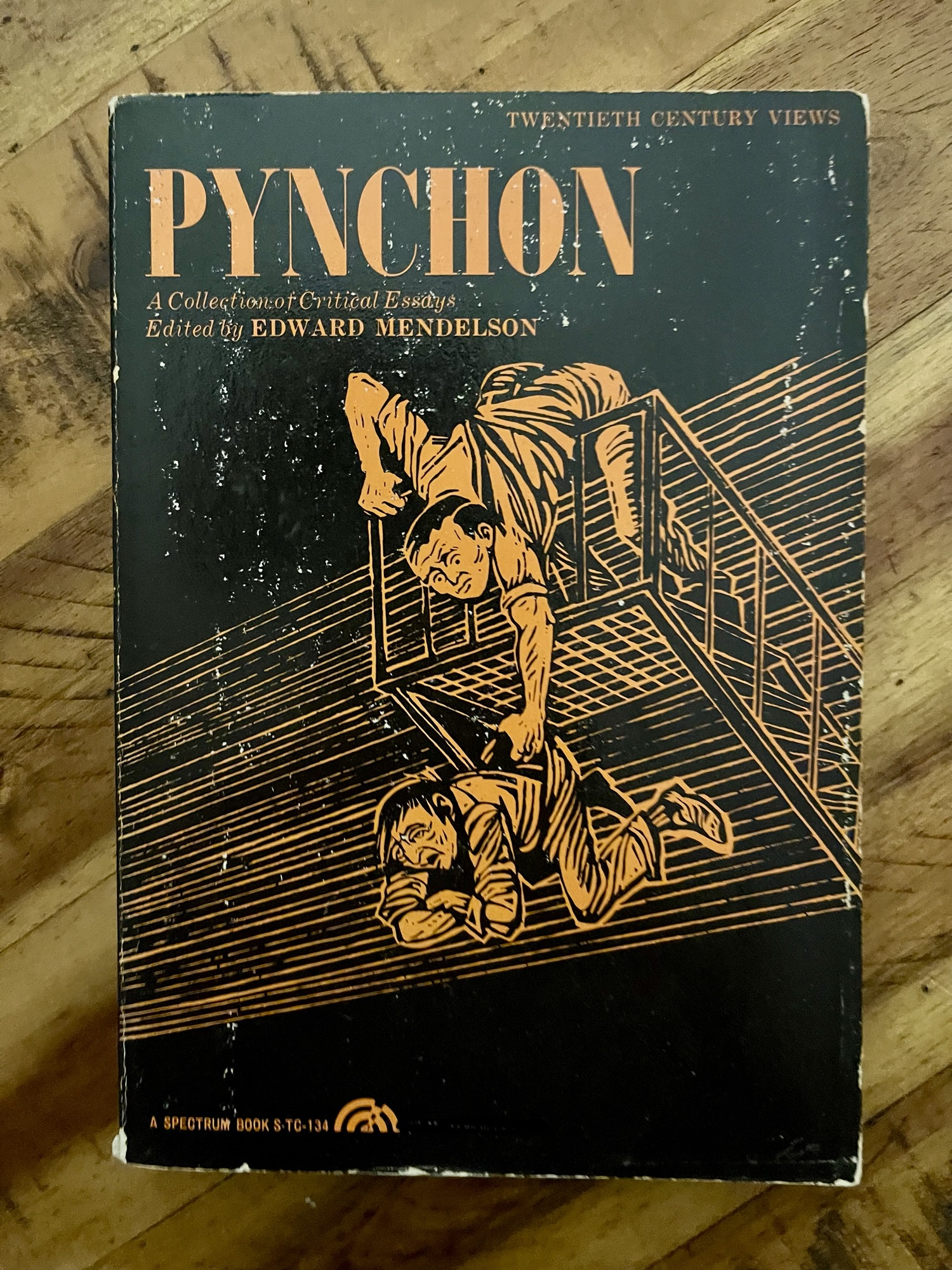

Thursday was the second Thursday of May, 2025, making it 8 May 2025, the 88th birthday of Thomas Pynchon. For over a decade now, I’ve celebrate my favorite author’s birthday on this blog as part of the Pynchon in Public “tradition,” but I couldn’t muster what I had planned (a riff on the forthcoming Vineland adaptation and the new novel, Shadow Ticket). The notes I sketched in late April for the piece strike me as silly, glib even.

That Thursday afternoon my friend’s wife (widow? fuck!) called me to ask me to deliver the eulogy at his “Celebration of Life Ceremony” at the beach the following Thursday. I started working on it. It was painful but somehow easy to write. It was very, very difficult to edit.

On Friday, Jon Lackman and Zack Pinson’s biography The Woman with Fifty Faces: Maria Lani and the Greatest Art Heist That Never Was arrived at Biblioklept World Headquarters. My daughter had seven girls over to make their own pizzas that night. I read The Woman with Fifty Faces in one sitting; it was wonderful. It was the first thing I’d read that was not in some way connected to my friend’s death. I loved the experience of reading it. It offered relief.

This Friday, the second one of May, 2025 was the first day I hadn’t broken down at some point. I was absorbed in a study of grief. I was trying to shape my memories into something tangible, or at least something having a form, which is to say, something formal. I was googling things like, how long should eulogy be words. I was on the phone with old friends, replying to emails and messages from old friends. I was also contending with acquaintances I barely recalled, and none too fondly, who luridly “reached out” wanting details under the guise of “offering condolences.” I was amassing words.

More review copies on Saturday. Friends from out of town came over and we all drank far too much. There was another grief to attend to, a dead father, a man we had all adored, a fantastic storyteller, a raconteur even, if we’re feeling grand with our words, and I miss him too. My dead friend was a huge fan.

Sunday was Mother’s Day and I had forgotten about it. My own mother and father were both suffering from acute bronchitis, and I had held off on delivering the news of my friend, worried that they would worry for me and his family and his young young children. Sorrow is bad for health. But when family members reached out to me with sincere concern, prompted by the trickle of news on social media about the upcoming Celebration of Life — forgive me, I’m just gonna call it a funeral, it was a funeral, no matter what we want to say — anyway, the trickle turned into a stream, and then I called my mom with the news. I don’t have any physical proof like a recording, but her wailing immediate refusing disbelieving repeated NO sounded exactly like my own. But from a chronological position, it seems that I must have inherited that cry from her, no?

The next day she called me to tell me a story I’d never heard from either her or my friend — years ago, when I was living in Tokyo and he was still in Jacksonville, he stopped by my parents house, unannounced, simply because he was driving by and wanted to share some of my latest emailed updates with my parents and hoped that they would share some too. “We had spaghetti dinner together. It was so nice,” my mother said. My bones turned into jelly and my eyes took to sweating.

This next day was of course the second Monday of May, 2025, the one week mark. The document I’d titled “eulogy” was a massive incoherent patchwork of memories, good times, riffs, and material cribbed from friends, including an entire email so beautifully-written from a friend that I thought about just passing it off as my own. The document also included five Langston Hughes poems, several lines from Moby-Dick, two longish quotes from Emerson (neither of which I understood or understand), a chapter on mourning rites from an early-twentieth century anthropology book, numerous David Berman and David Bowie lyrics, and the entirety of Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art.” It was at least 9,000 words longer than it should be.

I don’t remember anything about that Tuesday or Wednesday. Two or three books came in the mail, I think, and I finally drove in a car, I think. I think I remembered to attend the houseplants. I must have actually written the eulogy those days. What I remember mostly is sweating from the back of my legs, stripping away all the ornament and artifice I’d borrowed from literature and poetry and philosophy. I practiced reading it a few times. Some of my oldest, dearest, bestest friends arrived from the other side of the country that night.

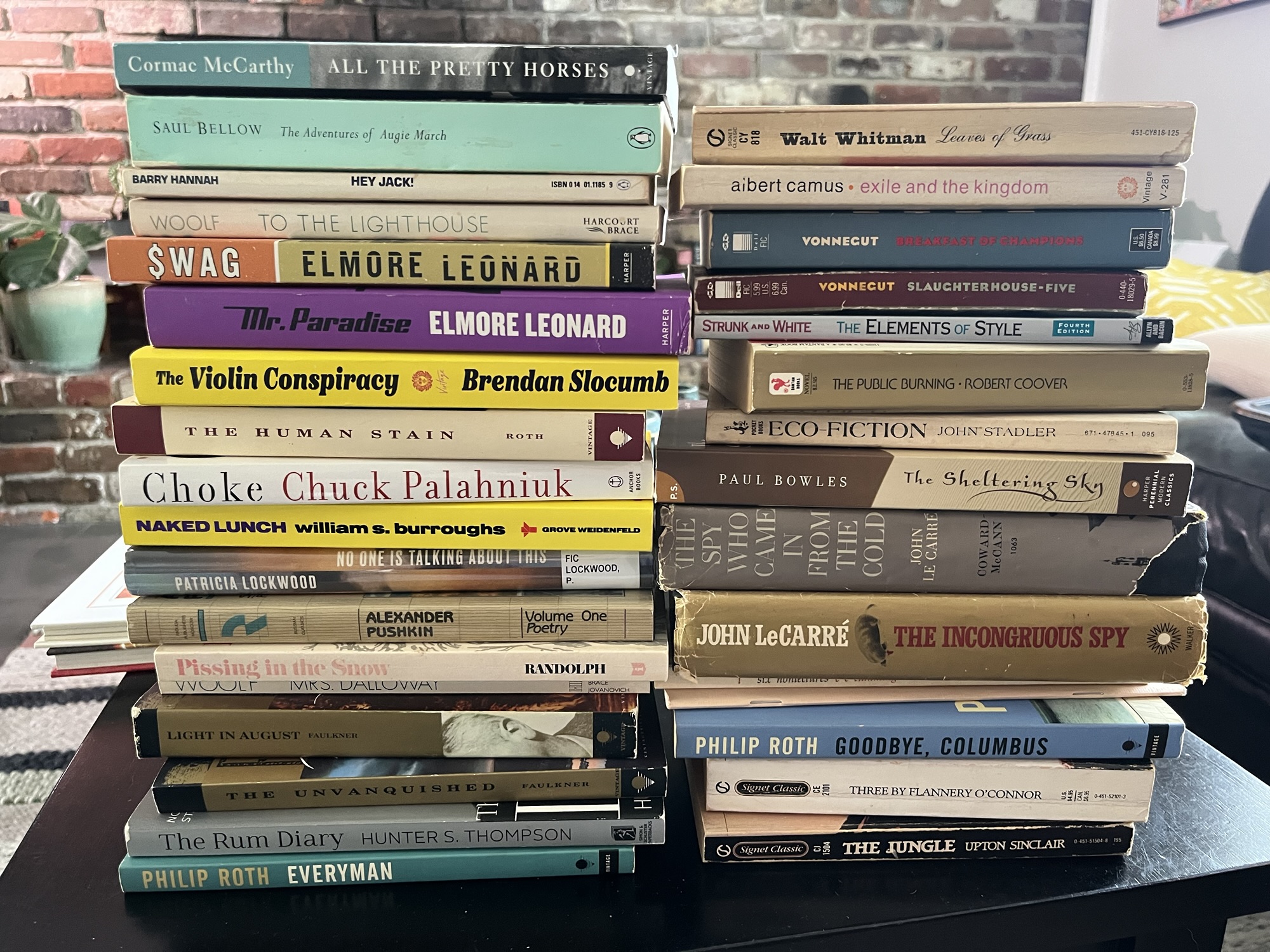

On Thursday those friends came over. My wife would drive us all out to the beach for the funeral. We started in on a few cheap watery domestics, maybe a little too early. The drive seemed interminable. I can’t really capture the vibe in the pavilion—and while I’m here not capturing things, I apologize if you’ve made it this far–I suppose this post is a bait-and-switch, what with the picture of a stack of books, right? The “Not really” in the blog’s title should really not be there at all, right? But the thing is, I need to get this all out, just like the thing I needed to write two weeks ago. If I don’t write it here I feel like I’ll never write anything here again. This is ostensibly a blog dedicated to art and literature, but it’s really more like a pastebook, a form of emotional and aesthetic recordkeeping that I’ve kept up for almost two decades now. The books in the picture above didn’t pile up as neatly as the photo suggests, but they did pile like that, causing me anxiety all month, reminding me that my attention was too thinned out. I was not as attentive to my children as I should have been in those weeks. My houseplants suffered. But so I have to let all that anxiety out here, and I’m sorry if it’s alienating to a potential audience, and I’m sorry to write that I am really writing this for me, for writing that If I don’t get these words out of my body I will not be able to write other words on this blog ever again—

—but the vibe in the pavilion. Very strange, moving from hysterical laughing to crying. Lots of great stories. The mic or PA went out in the middle of my eulogy so I ended up delivering it in the loudest voice I could muster. The pavilion was crammed, literally standing room only, such that the fire marshal or the marshal’s deputy or the person nominally in charge of these duties decreed that the doors be opened and about half of the people should mill about. The Atlantic breeze was lovely, even if it was in the high eighties. I saw and spoke to people I hadn’t seen in fifteen years, twenty years, thirty years. I was struck by how fucking old we all looked. My best friend’s brother looked exactly the same as their father had looked when we were thirteen, fourteen. I have felt iterations of old, tired, adult in my life; I’ve even felt mature and occasionally even wise (knowing that any trickle of wisdom I purchased through mistake and incaution). But I have never really felt grown up until last Thursday. I don’t really know what any of those words mean. We tossed flowers into the Atlantic’s chill waves.

I knew I’d have sand in my loafers all night. About a dozen of us went to a dive bar a mile away and got plastered. I had forgotten that there were still bars that people smoked in. A musician played four Seger covers in a row, keeping the beat with his prosthetic leg. The bar’s owner had a school desk set up right by the stage, where he was apparently attending to the bookkeeping, a pen in one hand, a menthol in the other. A vendor in a special vest kept trying to give us vape products. An older woman showed up after midnight and established an ad hoc outdoor kitchen where she fried lumpia, which we ate in large quantities. She told us several dirty jokes where the punchlines were, without variation, oral sex. We missed our friend; he would’ve had a great time that night.

My sweet wife, designated driver, got me and the boys over the river and back home, putting up with our arguing over Zappa. She fell into our mistake back at home though, committing herself to vodka while we polished off a bottle of bourbon.

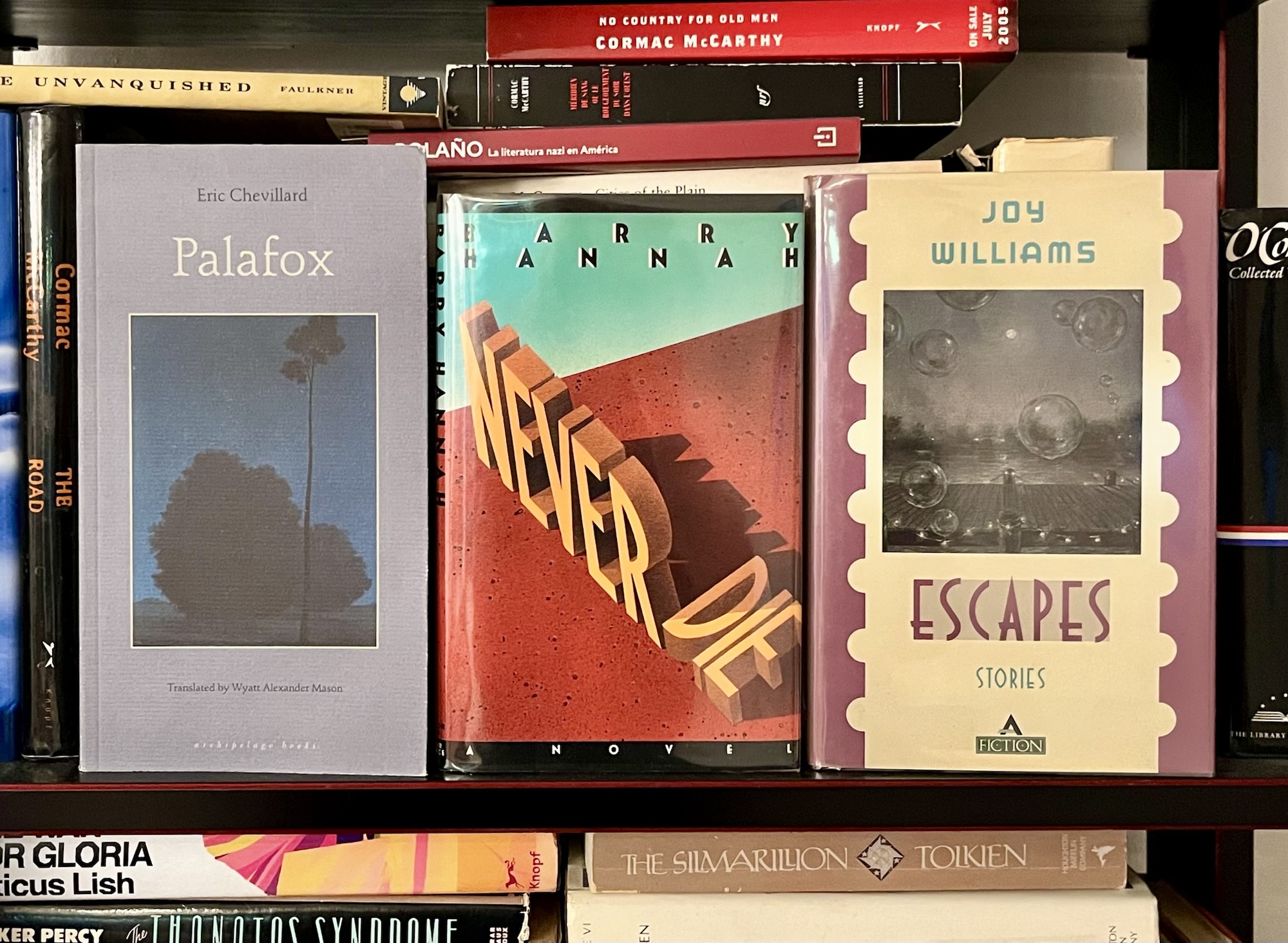

Friday was an agony overcome in small measures by barbecue and beers, a slow stretching anti-wake of sorts where folks drifted in and out of our house. It was a strange party, but also so wonderful, so full of love and support and all things corny, I suppose. I gave away a copy of Moby-Dick (a Norton Crit) and my backup copy of Gravity’s Rainbow. I foisted a redundant Barry Hannah novel on a friend. Folks drifted off in lacy jags, or at least that’s how I’ll choose to characterize it here. A few stayed the night, sleeping on couches in a half-remembered skill perfected and then promptly abandoned over twenty years ago.

I didn’t really sleep, again. I had only really slept one night out of the past lost eleven days, and then I suppose on the point of exhaustion. I had not eaten healthily and over three days and nights had overindulged in alcohol in a way I had not in years. I drove my friend to the airport so he could return to his family in Portland, got out of my car around 11am on Saturday, aiming myself for my bed. I was having difficulty breathing, or not so much difficulty breathing, as sharp pain when breathing. This pain was enormously exacerbated when I lay down and relieved somewhat when I stood. The pain intensified throughout the day; it was something new. I weird dull pain in my neck and the back of my throat. Not esophageal, exactly. By three it was almost impossible to breathe anything but the most shallow breaths without intense pain; I could not lie down because of the pain, despite being exhausted. My wife insisted we visit an urgent care clinic in a CVS; the nice doctor there insisted with caring urgency that I go to the closest emergency room. Six hours and lots of tests later I was back at home in even worse pain but with a diagnosis of pericarditis, likely brought on from stress, and a prescription for prednisone.

On the third Sunday of March, 2025, I was finally able to truly fall asleep for the first time in weeks. I felt a bit better on Monday, although the steroids have made me feel a little loco I’ll admit. Today was the first day I’ve felt anything close to normal in a while–I mowed the lawn, which had gotten a bit wild, and attended many of my poor neglected houseplants. And then I exorcised the stack of books that had stackingly stacked up, a pillar of publishers’ good will that radiated anxiety-inducing waves. Let this post be a totem against that. I look forward to peeking in to some and reading others in full and maybe even ignoring one or two (not yours if somehow yours is included in the stack; not yours). And all my apologies again.

I feel better now. Just different.