I 1 think that there is a terrible possibility now, in the World 2. We may not brush it away, we must look at it. It is possible that They 3 will not die. That it is now within the state of Their art to go on forever 4—though we, of course, will keep dying as we always have. Death 5 has been the source of Their power. It was easy enough for us to see that. If we are here once, only once 6, then clearly we are here to take what we can while we may 7. If They have taken much more, and taken not only from Earth but also from us 8 —well, why begrudge Them, when they’re just as doomed to die as we are? All in the same boat, all under the same shadow…yes…yes. But is that really true? Or is it the best, and the most carefully propagated, of all Their lies, known and unknown? 9

1 The speaker here is Father Rapier, a very minor character, one of Pynchon’s heroes of the Counterforce, the Preterite who rally (if that is the right verb, which it isn’t) around the unraveling spirit of Slothrop against the Elect.

Father Rapier is “a Jesuit . . . here to preach, like his colleague Teilhard de Chardin, against return. Here to say that critical mass cannot be ignored. Once the technical means of control have reached a certain size, a certain degree of being connected one to another, the chances for freedom are over for good.”

Rapier preaches his “Critical Mass” in a cottage in the bizarro-Limbo headquarters of the Counterforce; his shack is appropriately beshingled with the sign “DEVIL’S ADVOCATE.”

Pynchon’s Counterforce points to a coming community. Indeed, Gravity’s Rainbow might be seen as an imaginative study of postwar communities, of new forms of social organization (social organizations tellingly organized against the They): The Counterforce of disaffected rebels; the Sudwest Hereros assembling their 00001 rocket; the Argentine anarchists; the homosexuals liberated from Dora; the Anubis orgiasts (orgiers? orgy-goers? What’s the word for orgy participants?)—etc. Each of these coming communities attempts to synthesize the detritus of the War into Something New. And speaking of synthesis—

Rapier’s “colleague [Pierre] Teilhard de Chardin” (1881-1955) tried to synthesize science and spirituality in what he called an Omega Point, a spiritual/physical singularity, a condensation of spirit and mass into a “supreme consciousness”: Christ: God: Logos. Or, in Pynchon’s Rapier wit: Critical Mass.

Rapier rails against systems of control: The Elect will not fight the coming postWar Preterite communities directly, but rather enslave them via byzantine bureaucracies.

2

Cf. A.E. Waite’s The Pictorial Key to Tarot (1910), one of Pynchon’s sources for Gravity’s Rainbow. Some of the language here (which I’ve taken the liberty of highlighting) echoes Rapier’s Critical Mass/de Chardin’s Omega Point:

It represents also the perfection and end of the Cosmos, the secret which is within it, the rapture of the universe when it understands itself in God. It is further the state of the soul in the consciousness of Divine Vision, reflected from the self-knowing spirit. But these meanings are without prejudice to that which I have said concerning it on the material side. It has more than one message on the macrocosmic side and is, for example, the state of the restored world when the law of manifestation shall have been carried to the highest degree of natural perfection. But it is perhaps more especially a story of the past, referring to that day when all was declared to be good, when the morning stars sang together and all the Sons of God shouted for joy.

The World is what Pynchon and Gravity’s Rainbow are most interested in—both its past and its coming communities.

Significantly, The World is the final card in Captain Dominus Blicero Weissmann’s tarot (see page 746):

In his thorough physical description of the World tarot card, A.E. Waite describes the central figure surrounded by “an elliptic garland…a chain of flowers intended to symbolize all sensible things.” I cannot help but see in the card an impossible ouroboros; an ouroboros with four heads corresponding to the “four living creatures of the Apocalypse and Ezekiel’s vision, attributed to the evangelists in Christian symbolism” which we find in the card’s corners. The ouroboros is minor trope in Gravity’s Rainbow.

3 The Elect. The baddies.

4 Rapier will, a few lines later, compare Them to vampires.

Here—and elsewhere in Pynchon (most clearly and perhaps most cogently in Against the Day)—the Elect—the They—manipulate and monopolize the earth’s resources in order to prolong their dominance. Those resources include humans: The Preterite: the low: the feebs.

5

A.E. Waite again; again, I’ve highlighted in boldface phrases that suit my own purposes for this riff:

The veil or mask of life is perpetuated in change, transformation and passage from lower to higher, and this is more fitly represented in the rectified Tarot by one of the apocalyptic visions than by the crude notion of the reaping skeleton. Behind it lies the whole world of ascent in the spirit. The mysterious horseman moves slowly, bearing a black banner emblazoned with the Mystic Rose, which signifies life. Between two pillars on the verge of the horizon there shines the sun of immortality. The horseman carries no visible weapon, but king and child and maiden fall before him, while a prelate with clasped hands awaits his end. … The natural transit of man to the next stage of his being either is or may be one form of his progress, but the exotic and almost unknown entrance, while still in this life, into the state of mystical death is a change in the form of consciousness and the passage into a state to which ordinary death is neither the path nor gate. The existing occult explanations of the 13th card are, on the whole, better than usual, rebirth, creation, destination, renewal, and the rest.

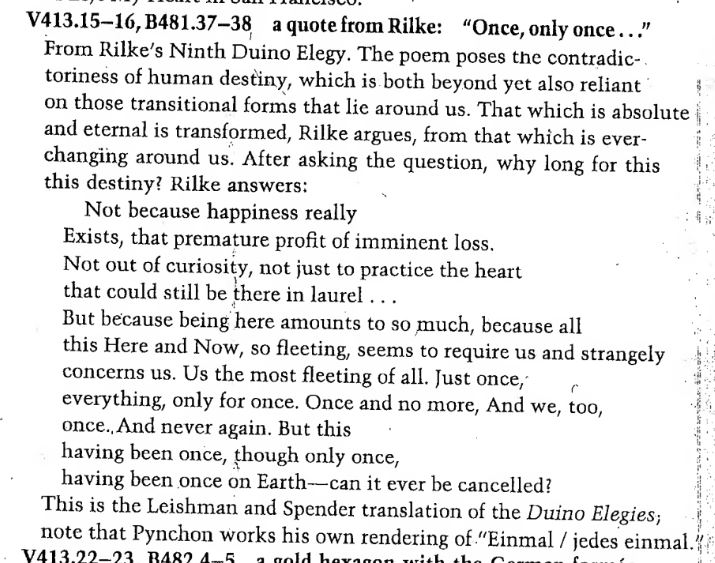

6 If we are here once (only once), then eternal recurrence is a nonstarter.

The phrase clearly echoes lines from one of Pynchon’s major GR sources, Rainer Maria Rilke’s mystical Duino Elegies (1923). From “Ninth Elegy”:

Everyone once, once only. Just once and no more.

And we also once, Never again. But this having been

once, although only once, to have been of the earth,

seems irrevocable.

Pynchon’s phrasing also echoes William Bright’s 1866 hymn, “Once, Only Once, and Once for All,” which begins:

Once, only once, and once for all,

his precious life he gave;

before the cross in faith we fall,

and own it strong to save.

7 In “To the Virgins, to Make Much of Time, Robert Herrick (1591-1674) advised

Gather ye rosebuds while ye may,

Old Time is still a-flying;

And this same flower that smiles today

Tomorrow will be dying.

Seems like a Preterite Sermon.

8 Cf. note 4. Throughout GR, the exploitation of the earth’s natural resources is a persistent if minor theme. Gravity’s Rainbow’s ecological critiques are overlooked perhaps because it’s a given in Pynchon’s critique that They would use ecological capital and human capital without regard. Consider the Slothrop family, which made its non-fortune by milling trees into “Money, shit, and The Word” — papers the real value of which Pynchon invites us to interrogate.

9 Pynchon’s mouthpieces often hedge their bets in eithers and ors, zeroes and ones. We systems and They systems, in the parlance of the Counterforce. Are we all under the same shadow (of Death? of the falling rocket?) Are we all in the same boat?—which is to say, are we all working together toward the same coming community—are we rowing in the same direction?

Oh I think you know the answer.