I ducked out of work maybe a little bit early on Friday and filled a brown paper bag with books at a Friends of the Library sale.

I picked up some hardback first editions of books I already own in cheaper formats–Lucia Berlin’s A Manual for Cleaning Women, Denis Johnson’s The Laughing Monsters, P.D. James’s The Children of Men, and Ben Marcus’s Leaving the Sea. I also got hardcover editions of Rachel Cusk’s Second Place, Amy Hempel’s Sing to It, Atticus Lish’s The War for Gloria, and Eugenio Corti’s The Red Horse.

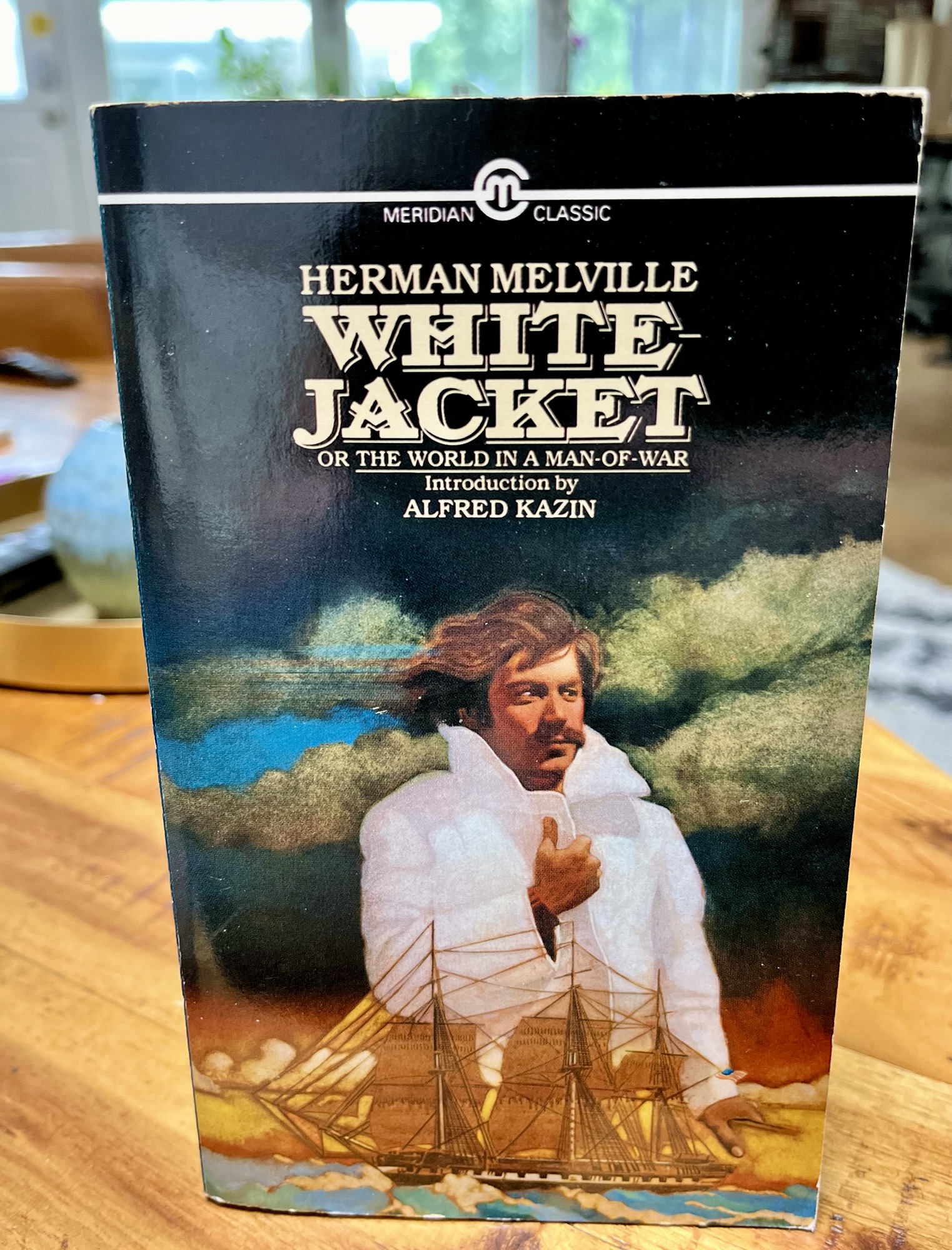

I also grabbed some duplicates or alternate paperback editions of books I already own, including an academically-oriented edition of Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives, Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler, and William Faulkner’s Light in August. I gave the Calvino to my son; the Stein is for a colleague. I’ll give Light in August to a student. (I got the same edition of the Faulkner at the last Friends of the Library sale I went to; my son claimed it.) I’ll also probably offer the Bourdain memoir to a student. I’m pretty sure we have a copy of Kitchen Confidential somewhere around the house. I couldn’t pass up on the cheap mass-market copy of Melville’s White Jacket. I mean, just look at this cover—dude’s wearing a white jacket—

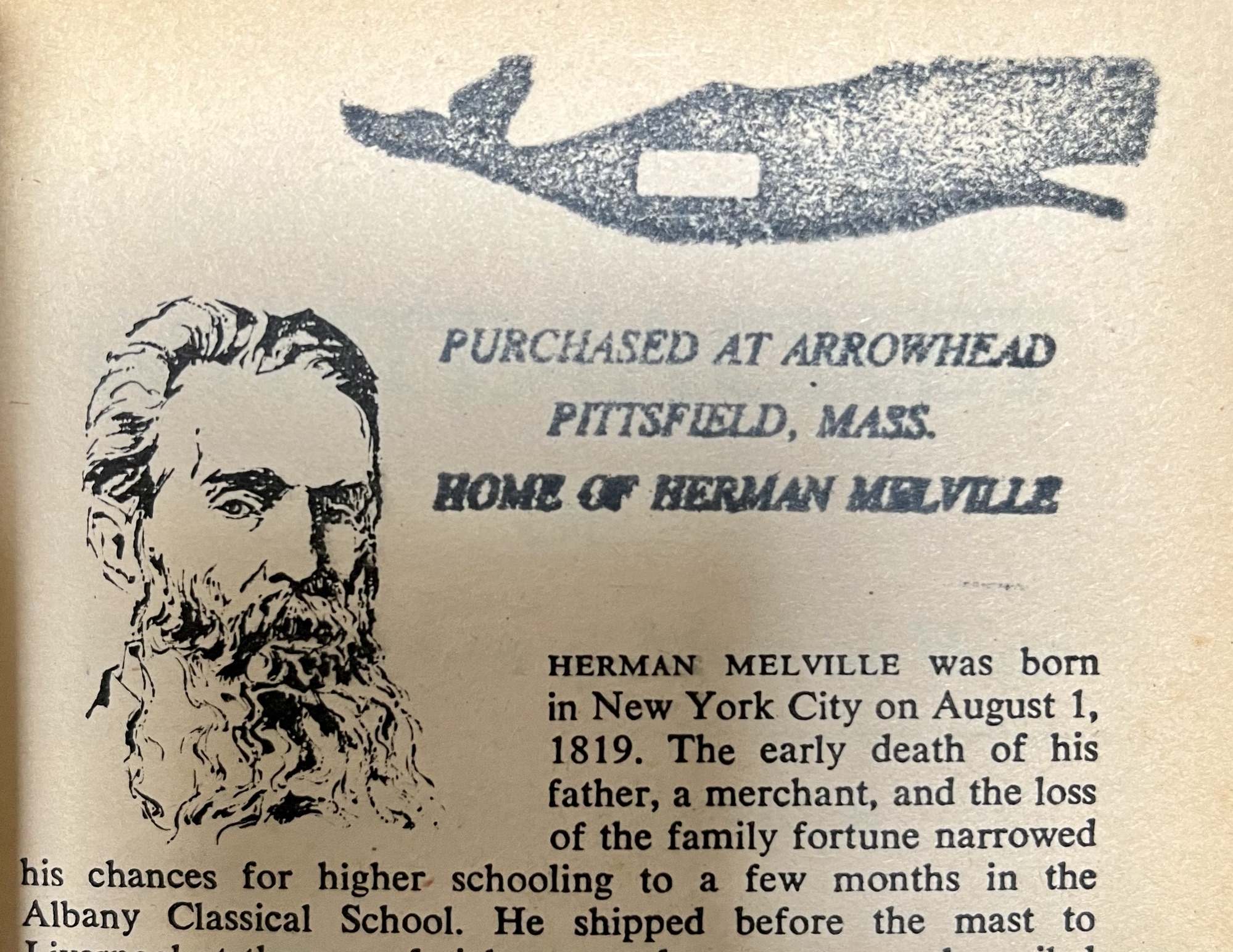

The book also bears a stamp claiming it originated (in a sense) at the old Melville Manse, Arrowhead:

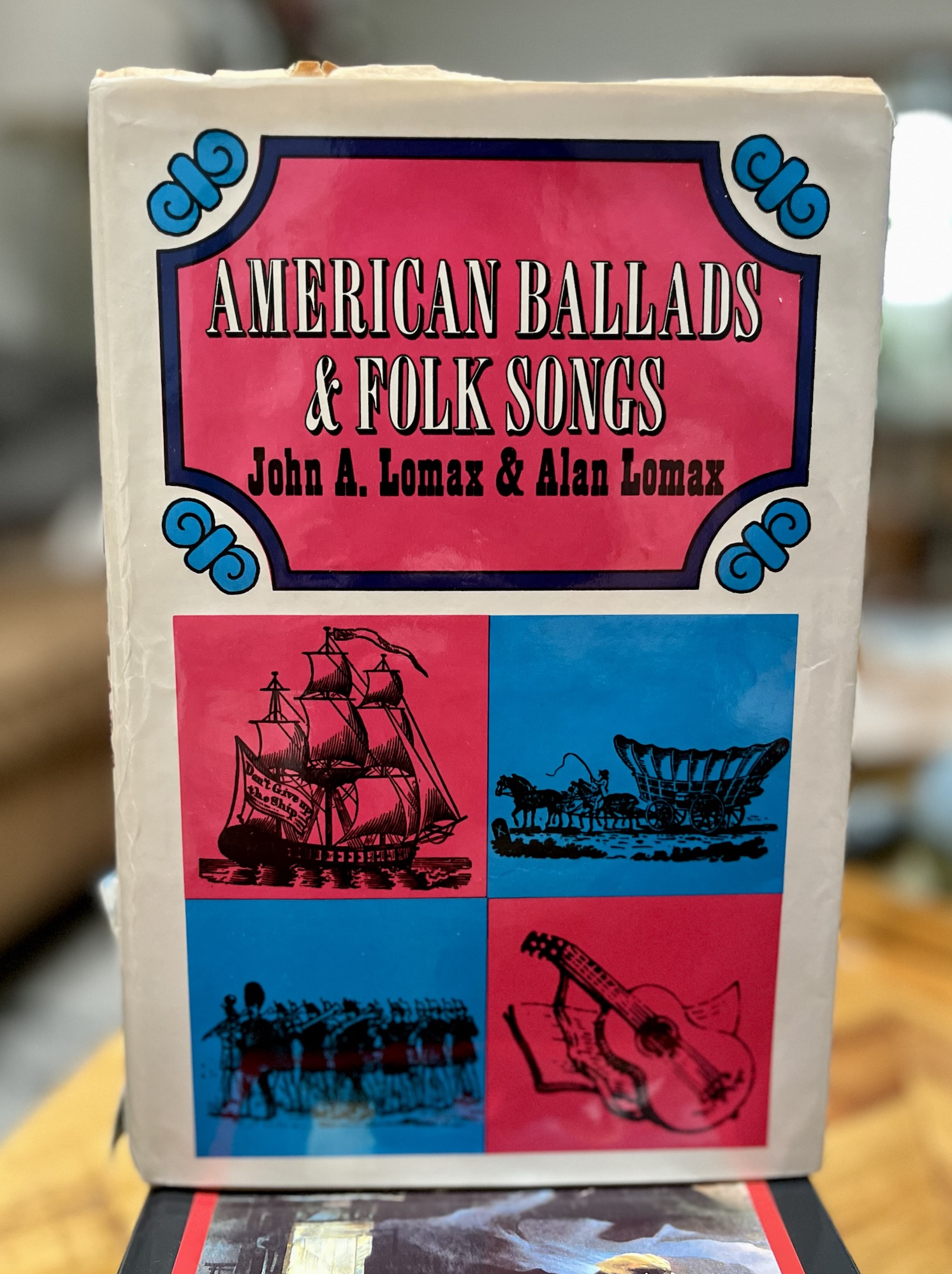

I also couldn’t resist letting a paperback copy of Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport take up a lot of real estate in my paper grocery bag. The hype has died down enough for me to perhaps eventually sink into it. The edition of Alan & John Lomax’s American Ballads & Folk Songs is kinda beat up, but it’s got a lovely cover:

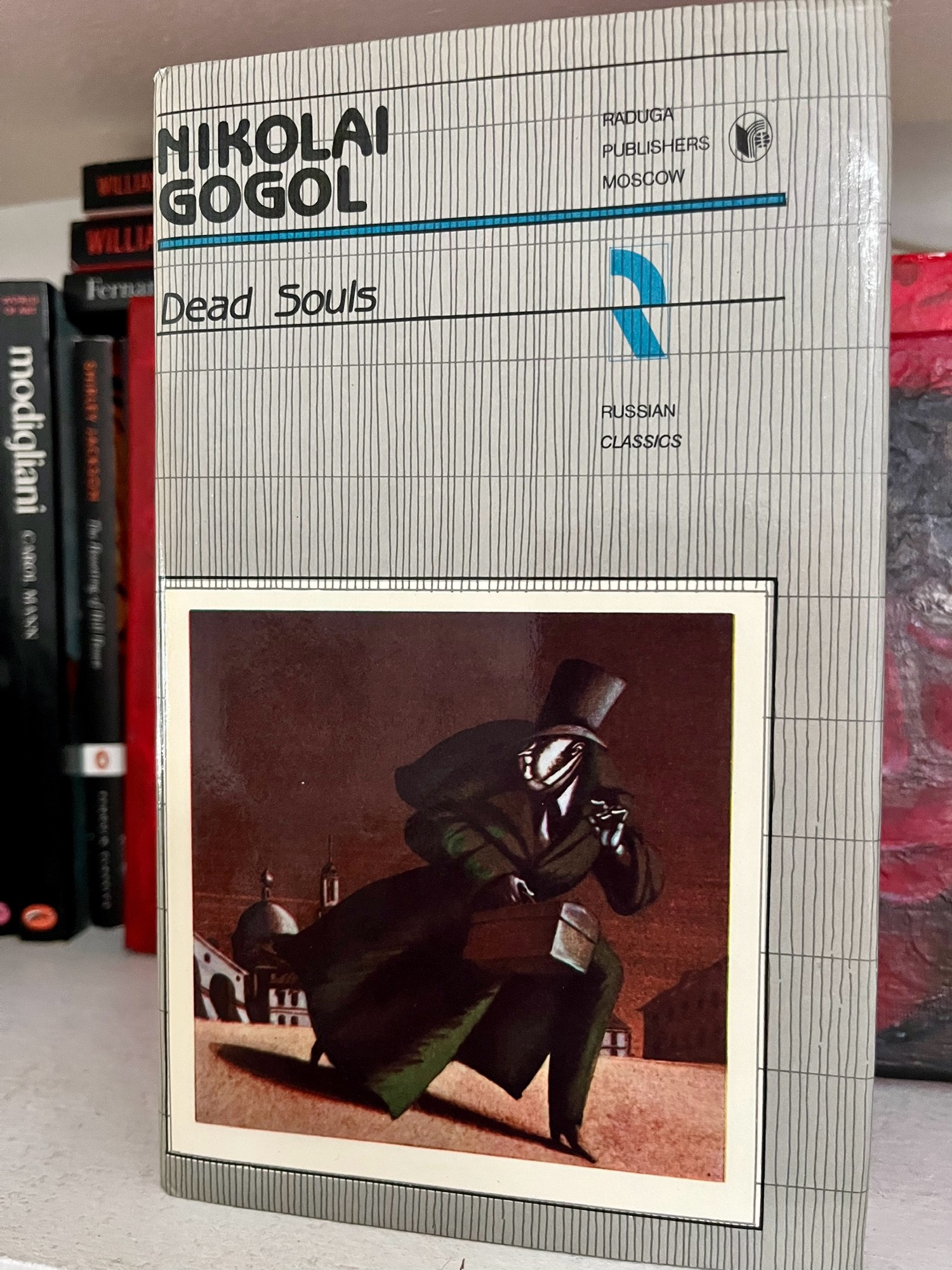

I was also attracted to this strange edition of Nikolai Gogol’s Dead Souls. It’s a 1987 hardback from the Soviet house Raduga Publishers, featuring a full-color portrait of Gogol and blue (?) page headings. The translation is by Christopher English and the book was printed in the U.S.S.R.—I’m not really sure who the intended audience was.

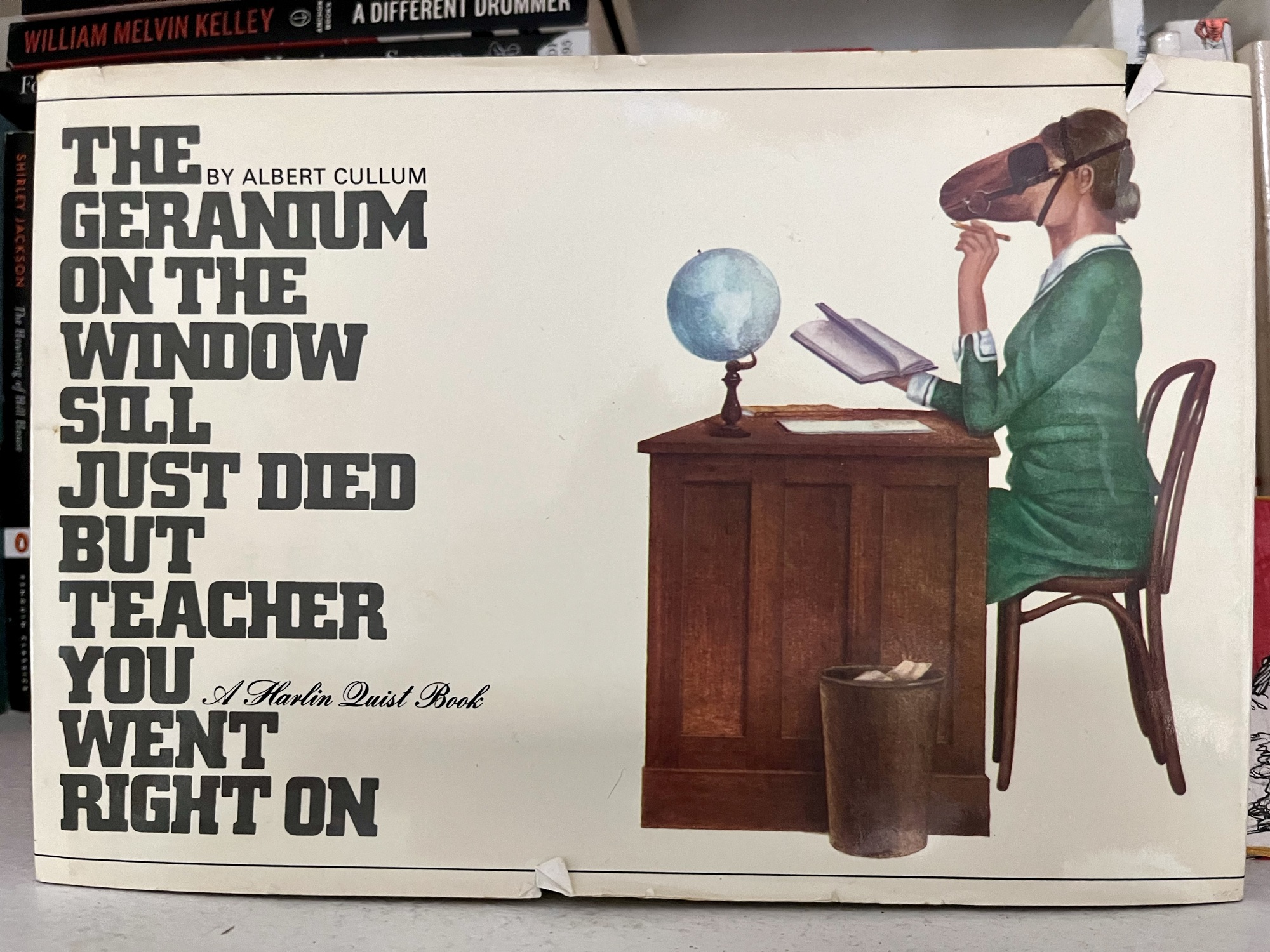

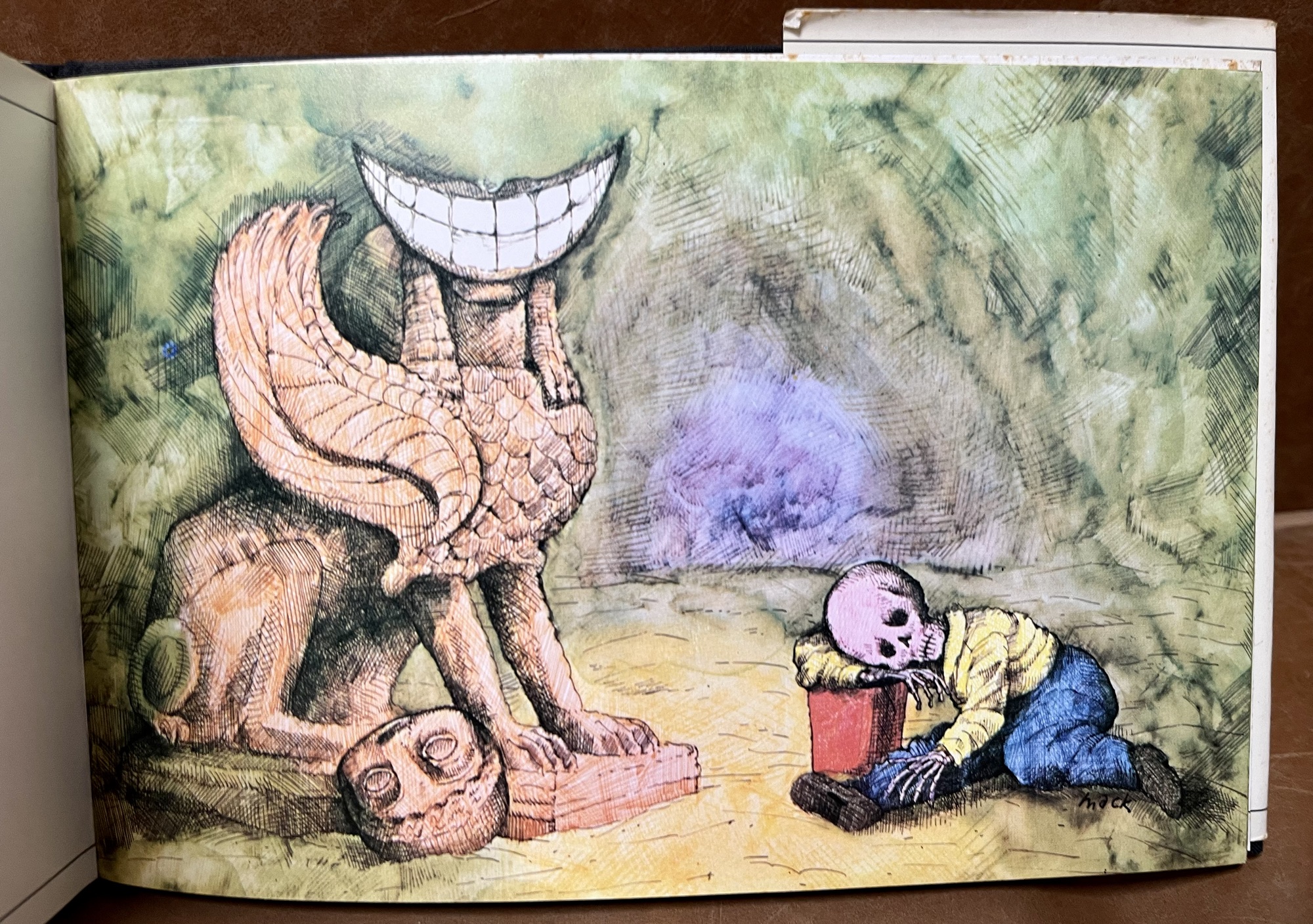

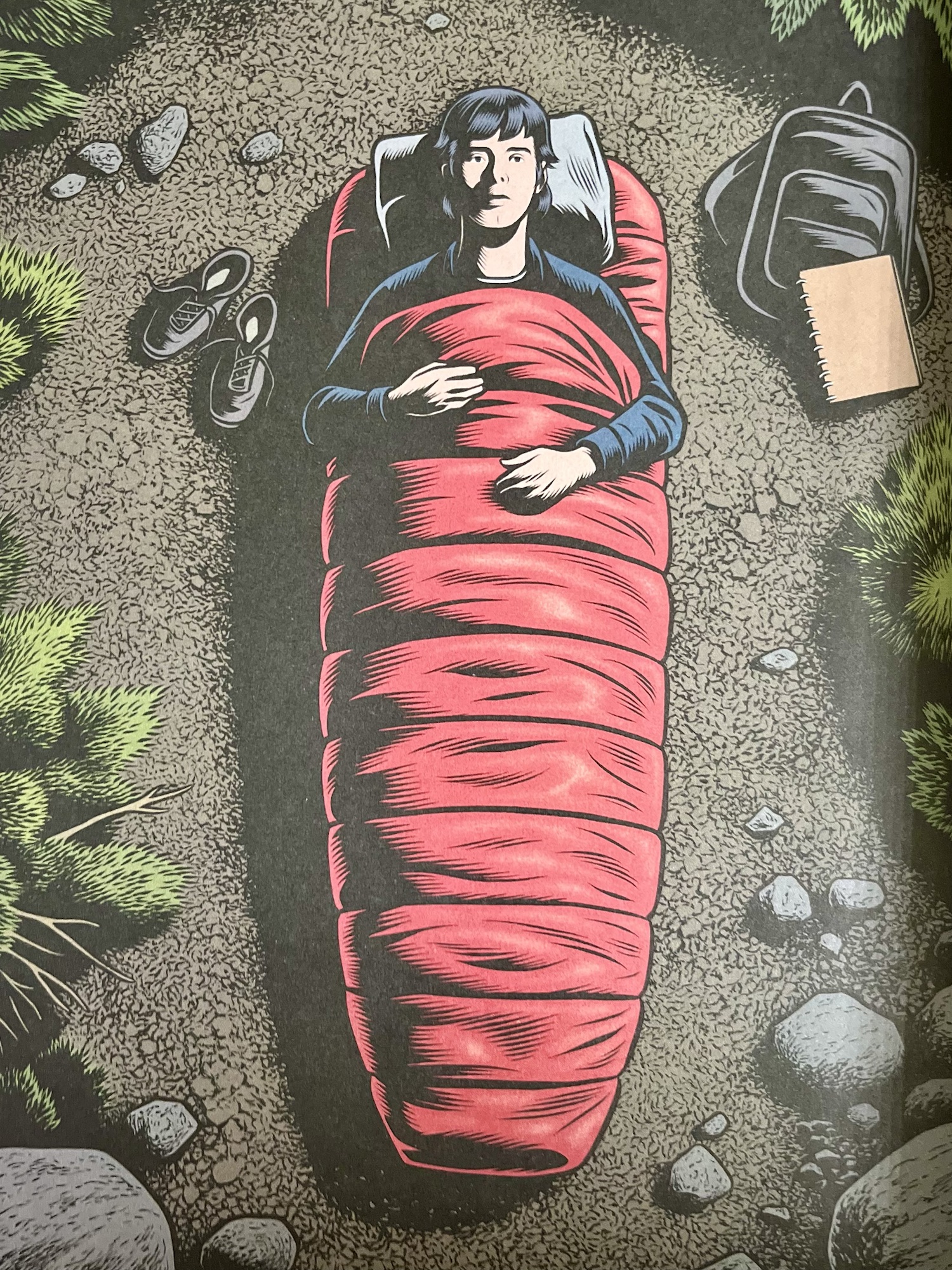

Albert Cullum’s The Geranium in the Window Sill Just Died But Teacher You Went Right On was another oddity I came across. Ostensibly a children’s book, The Geranium ultimately seems aimed at teachers. It features illustrations on every other page, each one by a different artist; many are remarkable, like this one by Stanley Mack–

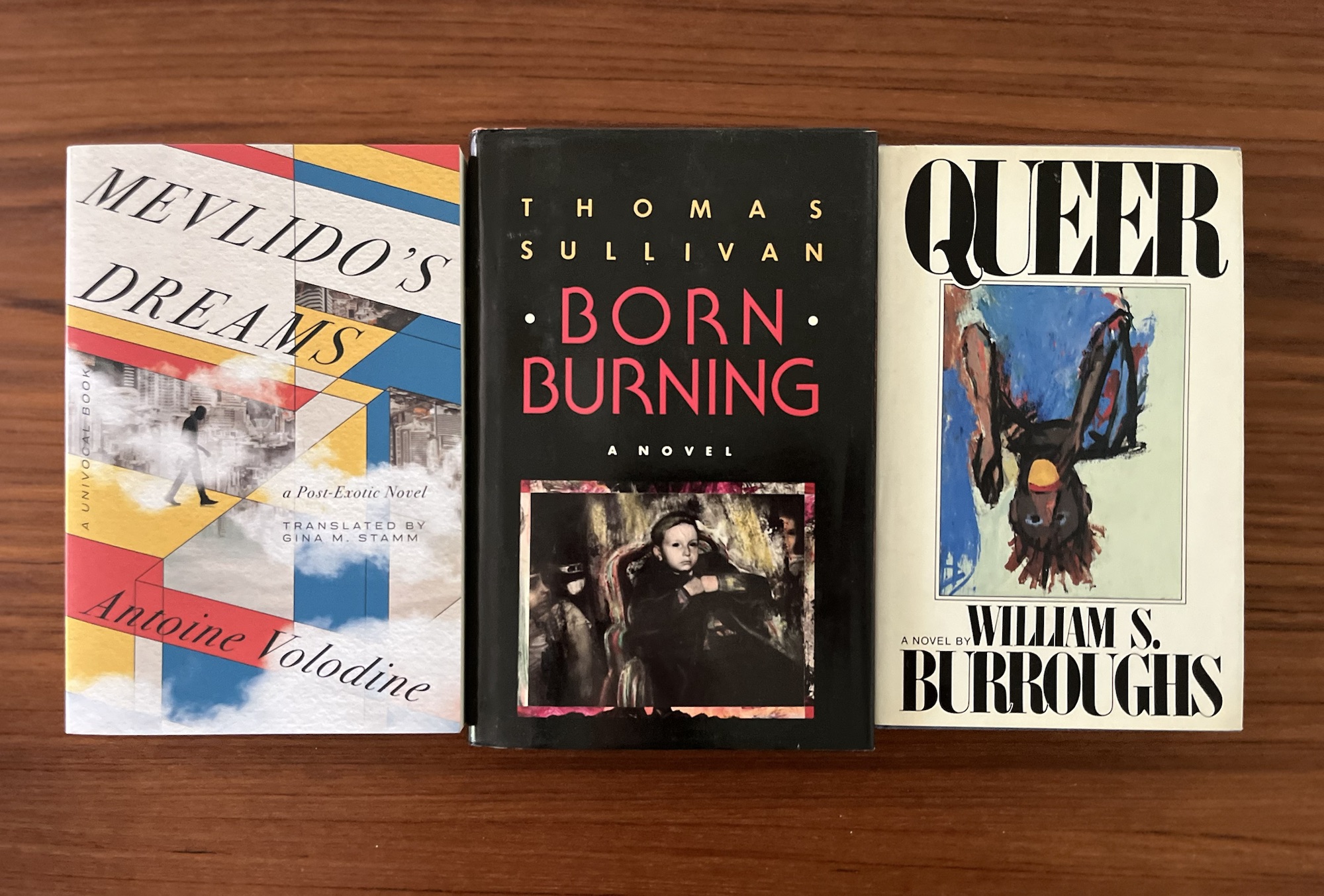

There were a few titles, not pictured in the image at the top of this post, that I grabbed to cram into my bag simply because I had extra room at the end. I can usually offset the ten dollar bag fee by identifying a handful of pristine trade paperbacks that my local used bookstore will take for trade credit. So maybe I’m not, like, really offsetting the ten dollar fee so much as redirecting it toward obtaining more books.

There were plenty of titles at this particular sale that I would’ve crammed into the bag maybe ten or fifteen years ago—lots of books by Haruki Marukami, who has never been my guy, Jonathan Lethem (who I once really loved), Michael Chabon, Irvine Welsh, and even Chuck Palahniuk (there was a time when I was younger and had a broader range of friends that I could’ve given Palahniuk titles away easily). But I ended up imagining some younger person showing up to the sale, maybe today, Saturday, filling up a bag with titles that promised something beyond the YA formula stuff that makes up their current literary diet.

And if I imagined a younger person growing their library, I also imagined some of the older people whose collections had clearly ended up at the sale. Beyond the obvious airport thrillers and glut of titles by fiction factory Authors™, there were sets of strange, off-brand looking fantasy series in hardback, a seemingly-full run of Agatha Christie mysteries (also in hardback), Westerns no one will read again. Other people’s oddities ended up here; their children had no place for them, having subscribed to their own burdensome addictions.

I’ll have to give away all these books I’ve acquired at some point. But there’s joy in that too.