Today, I plan to tube a portion of the Ichetucknee River, a cherished aorta of north Florida’s freshwater vasculature. It’s far and away the most vaunted tubing destination in the state, and I feel considerable pressure to get the tube into maximum spruceness and tumescence before my voyage.

In the town of Fort White, 35 miles northwest of Gainesville at the edge of Ichetucknee Springs State Park, we pull over at a tube-rental place to attend to maintenance and then install the Tube Pro booster saddle I’d thought unnecessary but, luckily, brought along anyway. My craft’s improved ergonomics should help undo the damage to my back.

The proprietress of the Ichetucknee Tube Center is a pretty woman named Linda Soride, and we chat for a moment before a purple, circa-1987 Camaro, pulsing with megabass, pulls up. As she turns away to diagnose the occupants’ needs, I fall a little bit in love with Linda. My mind drifts and I see myself, having patented the tube design, return to the ITC to license it exclusively to her. Revenues soar, and we soon depart the run-down filling station for a grand neon showroom. I’m the muscle of the operation—keeping the compressors shipshape, manning the patch kit—while Linda remains its comely public face. At the close of business each day, we head to the Ichetucknee and go floating off together, accompanied only by cool waters, cheering egrets, and some Riunite on ice.

Minutes later, I trot my tube—freshly inflated, booster seat in place—over to Linda. “This is just the prototype,” I rave proudly. “Once I get the kinks out, maybe you and me could do some business together.”

She shies away, cooing, “Maybe so, maybe so,” in a quiet, suspicious voice imparting the suggestion that I might be a little bit insane. (As Cheever’s story progresses, Neddy shows signs that he is not in command of his senses. The echo is unsettling.)

After I recover from this minor slight, Miss Bennett, who has to skip this portion of the journey to drive the car down, drops me at a designated embarkation point on the Ichetucknee. This river would inspire ecstasies in anyone with a pulse, but my ardor for spectacular scenery has reached a point of diminishing returns. I feel like a competitive eater tucking in to his 47th foie gras tart. The Ichetucknee offers more of the pellucid water and old-growth forests slung with buntings of Spanish moss. But while I’m relieved to discover, as advertised, no gators in sight, there’s also a disappointing shortage of amazing birdlife. Just the odd egret and heron, skulking on the bank like underpaid park employees. Plenty of people, though.

While my own capacity for amazement is waning, my superb invention, I would like to inform the proprietress of the ITC, is so enthusiastically admired by my fellow tubers that I’m to have no peace for the entire four-mile float. Seconds into the ride, two young women from St. Augustine beckon me into their flotilla. We enjoy a cozy interlude until a thickly built friend of theirs comes by and says “I want that tube” in a manner that is not unmenacing. I break away and into the path of a kayaking lady who pronounces mine “the Cadillac of tubes.” (A bespectacled professor following behind her describes it, a touch sneeringly, as “an interesting contraption.”) Even a fearsome river stud in a straw cowboy hat—reclining on a little inflatable yacht, trailing a miasma of marijuana fumes, a zaftig beauty on his arm—pauses to tell me that he deems the tube “a pretty badass setup.”

At last, I am among my people.

In this newfound fame and bliss, I drift on for hours. Toward the end, as I glide to the pullout, having made it halfway across Florida, the sky darkens. I struggle up the dock, where Miss Bennett waits for me in a shower of pelting rain.

From Wells Tower’s long essay, “The Tuber,” published in 2009 in Outside.

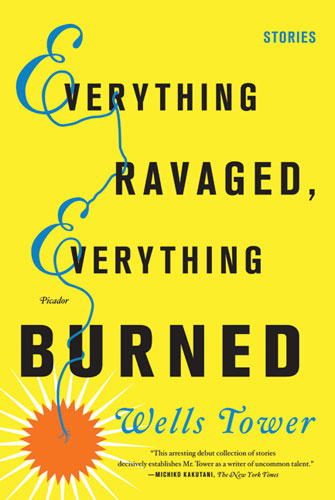

After reading Wells Tower’s short story “Opportunity Knocks!” in The Minus Times Collected the other day, I (again) poked around on the internet hoping to find any other uncollected stories by Tower. “Opportunity Knocks!” was first published in The Minus Times #29, back in 2009—the same year as Tower’s first (and so far, only) collection Everything Ravaged, Everything Burned. (I liked it a lot.)

I’ve appreciated the journalism and essayism that Tower has done over the past decade, but I somehow missed “The Tuber” until now. The essay is sort of a riff on John Cheever’s “The Swimmer,” with Tower traversing the springs and rivers of my home, North Florida, in a super-tube of his own devising. The section above details his time on the Ichetucknee River, my favorite tubing spot, and the scene of many of my favorite college days.

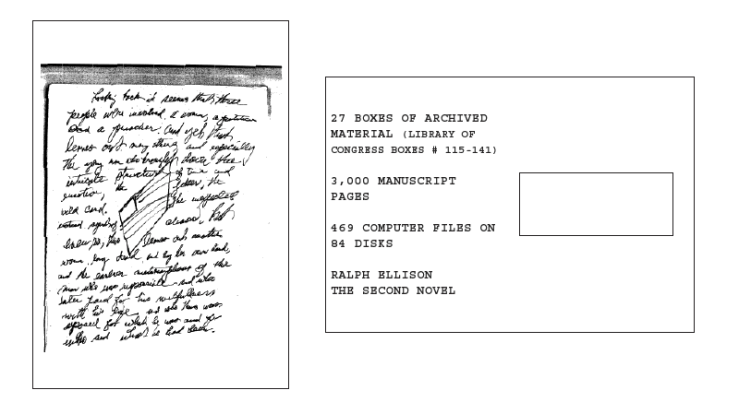

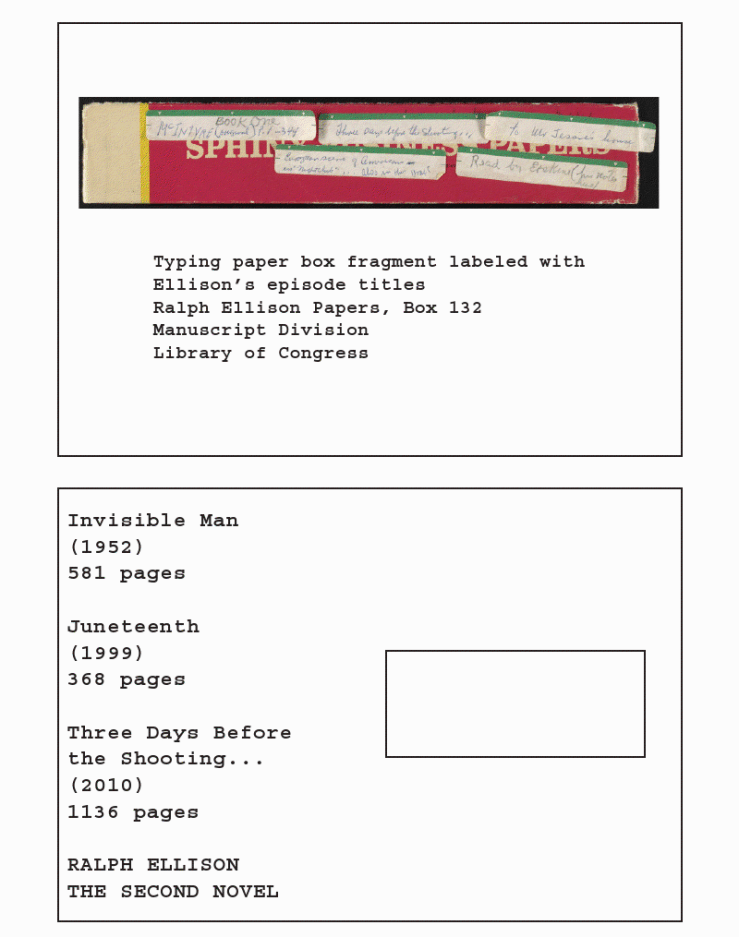

A second novel from Ralph Ellison? Wasn’t that Juneteenth, the posthumous work pieced together from thousands of pages and notes by Ellison’s literary executor, John Callahan? The one that was kinda sorta panned as a mess (or at least an incomplete vision)? A few weeks later, another postcard:

A second novel from Ralph Ellison? Wasn’t that Juneteenth, the posthumous work pieced together from thousands of pages and notes by Ellison’s literary executor, John Callahan? The one that was kinda sorta panned as a mess (or at least an incomplete vision)? A few weeks later, another postcard: So we were still a little confused. Was Three Days Before the Shooting… a more complete version of Juneteenth, or a wholly separate novel? A week or two later, a third postcard showed up with some answers: Ralph Ellison’s Three Days Before the Shooting… is a re-edit of the material originally presented as Juneteenth back in 1999, expanded from 368 pages to 1136 pages. Hopefully, Ellison’s vision will be restored here.

So we were still a little confused. Was Three Days Before the Shooting… a more complete version of Juneteenth, or a wholly separate novel? A week or two later, a third postcard showed up with some answers: Ralph Ellison’s Three Days Before the Shooting… is a re-edit of the material originally presented as Juneteenth back in 1999, expanded from 368 pages to 1136 pages. Hopefully, Ellison’s vision will be restored here.