From the essay “Treasure Hunting” by Umberto Eco; collected in Inventing the Enemy (translation by Richard Dixon).

From the essay “Treasure Hunting” by Umberto Eco; collected in Inventing the Enemy (translation by Richard Dixon).

I was a big a fan of Laurent Binet’s novel HHhH, so I was excited when I heard about his follow up, The Seventh Function of Language. I was especially excited when I learned that The Seventh Function took the death of Roland Barthes as its starting point and post-structuralism in general as its milieu. I audited the audiobook (translated by Sam Taylor and read with dry wry humor by Bronson Pinchot).

The audiobook is twelve hours. If it had been six hours I might have loved it. But twelve hours was a bit too much.

Wait. Sorry. What is the novel about though? you may ask. This is not a review and I am feeling lazy and not especially passionate about the book, so here is the publisher’s-blurb-as-summary:

Paris, 1980. The literary critic Roland Barthes dies – struck by a laundry van – after lunch with the presidential candidate François Mitterand. The world of letters mourns a tragic accident. But what if it wasn’t an accident at all? What if Barthes was murdered?

In The Seventh Function of Language, Laurent Binet spins a madcap secret history of the French intelligentsia, starring such luminaries as Jacques Derrida, Umberto Eco, Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, and Julia Kristeva – as well as the hapless police detective Jacques Bayard, whose new case will plunge him into the depths of literary theory. Soon Bayard finds himself in search of a lost manuscript by the linguist Roman Jakobson on the mysterious “seventh function of language.”

Kristeva! Eco! Derrida! All my childhood heroes are here!

So of course, y’know, I was interested. And I’m sure that the twenty-year-old version of me would have flipped out over Binet’s pastiche of postmodern theory and detective pulp fiction. But almost-forty me found the whole thing exhausting, a shaggy dog detective story with patches of the whole continental-philosophy-vs-analytical-philosophy debate sewn in with loose stitches.

The initial intellectual rush of what amounts to a Tel Quel fan fiction/murder-mystery/political thriller hybrid begins to wear thin about halfway through. Binet is smart and he’s writing about smart people, but the cleverness on display becomes irksome, especially when he’s drawing his characters’ big philosophical ideas in the broadest of strokes (Julia Kristeva arrives at her concept of abjection after a floating film on a glass of milk makes her ill).

Binet loves to cram his characters into social situations where they can wax philosophical (in the thinnest possible sense of that verb wax). The Seventh Function is larded with chatty cocktail parties where Kristeva and Foucault can toss out zinger after zinger. One of the novel’s centerpieces, an academic conference at Cornell, serves as an excuse for Binet to riff large (but shallow) on language philosophy. He even brings Chomsky and Searle to the conference to take on Derrida et al. (Binet also squeezes in a postmodern orgy here, in which Detective Bayard has a threesome with Hélène Cixous and Judith Butler). Such scenes are funny but baggy, overlong, and often feel like an excuse for Binet to show how clever he is. (And don’t even get me started on the fact that the novel’s central protagonist worries that he might be a character in a novel).

Binet is more successful at channeling his characters’ intellects during the high-risk debates of a secret society called the Logos Club. The best of these debates showcase thought-in-action, as Binet’s characters deconstruct various topics. Still, as engaging as some elements of the Logos Club debates are, they drag on too long, and the Club’s connection to the political-thriller aspect of the plot is pretty tenuous. Indeed, the novel is so loose that a minor character has to show up at the end and explain how all the elements connect for both the reader and detectives alike.

What’s probably most remarkable about The Seventh Function (despite the fact that it features a who’s-who of postmodern theory for its cast) is just how one-note the novel is. After all, it’s a mashup. As Anthony Domestico puts it in his (proper and insightful) review at The San Francisco Chronicle, “The novel is three parts Tom Clancy to two parts Theory SparkNotes to one part sex romp.” The Seventh Function of Language should be a lot more fun than it is. And it is fun at times, but not enough fun to sustain, say, twelve hours of an audiobook or 359 pages in hardcover.

As HHhH showed, Binet is a talented author, and even though The Seventh Function didn’t work for me, I’m interested to see what he does next. It’s possible that The Seventh Function didn’t float my proverbial boat precisely because I’m the ideal audience for the novel. If anything, it made me want to reread Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum—but The Seventh Function also reminded me that I read Eco’s semiotics-detective story as a much younger man—as a kid in my early twenties who probably would’ve loved Binet’s novel. So maybe I should leave well enough alone.

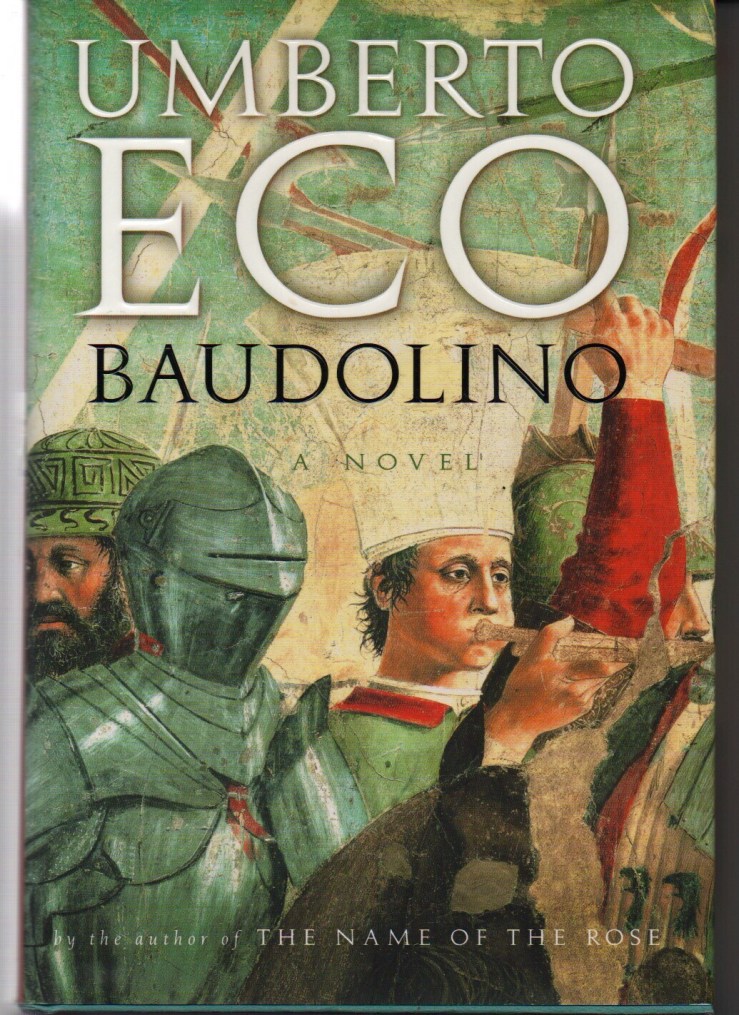

Baudolino by Umberto Eco. First edition hardback by Harcourt, 2002. English trans. by William Weaver. Jacket design by Vaughn Andrews, featuring a detail from the lefts side of Piero della Francesco’s fresco Battle between Heraclius and Chosroes.

I bought this in the last days of 2002 from the dollar table at the Barnes & Noble store near my parents house. I was 23 and had just moved home after living in Japan. I had no plans and was kind of depressed. I really can’t remember what I read around that time, but I know it wasn’t Baudolino. I didn’t get to it until the summer of 2011. It’s a fun, propulsive, sloppy quest narrative—bawdy, rich, a picaresque take on the (not-so-secret) mythological backgrounding of medieval Europe. It kind of unravels at the end.

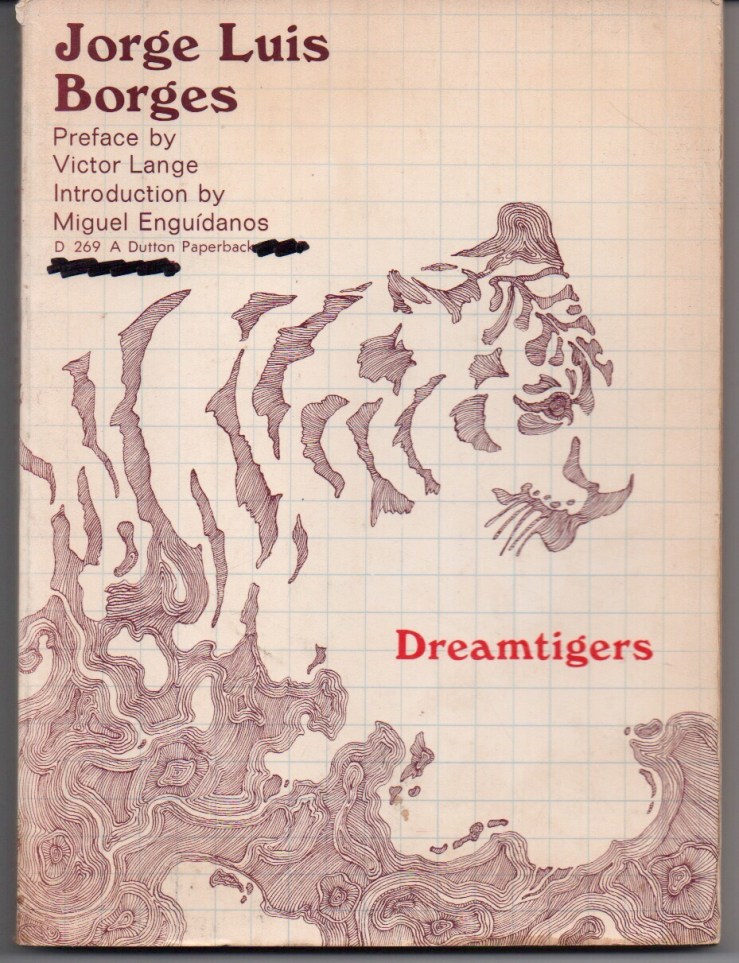

I had initially planned this Sunday’s Three Books post to feature three Eco titles as a sort of tribute to our deceased semiotician, but alas I only have two here at the house (The Name of the Rose is the other one). I lost my copy of Foucault’s Pendulum over a decade ago, and I gave a colleague my copy of Misreadings just a few months ago (she had expressed a certain distaste for The Prague Cemetery). My copy of On Literature is in my office (although if I’m being honest, I use a samizdat digital copy more often as a reference point). Eco was a sort of gateway drug though to his spiritual brothers, Calvino and Borges. I actually read both of them before Eco, but understood them better when approached after Eco. I don’t know if that makes any sense (and I don’t think it has to make any sense).

Dreamtigers by Jorge Luis Borges. An irregularly shaped trade paperback by E.P. Dutton & Co., 1970. English translation by Mildred Boyer (prose) and Harold Morland (poetry). Cover design by James McMullan. I love the cover and hate that a bookseller decided to mark out the original pricing with ugly Sharpie ink.

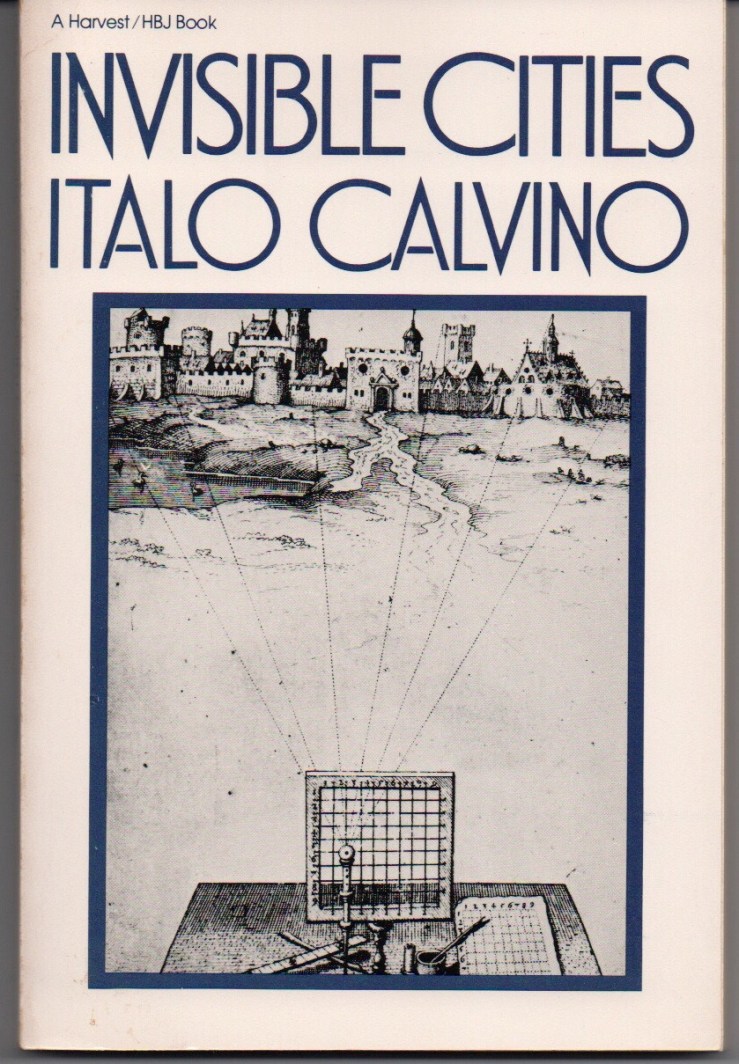

Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino. Harvest/HBJ trade paperback; no year given. English trans. by (Eco’s translator) William Weaver. Cover design by Louise Fili, employing a 17th-c. woodcut of a drawing screen. I first read Invisible Cities in 2002, in spots and places around Thailand. I read my friend’s copy; he had brought it with him to meet me there. He was the same guy who took my copy of Foucault’s Pendulum and never returned it.

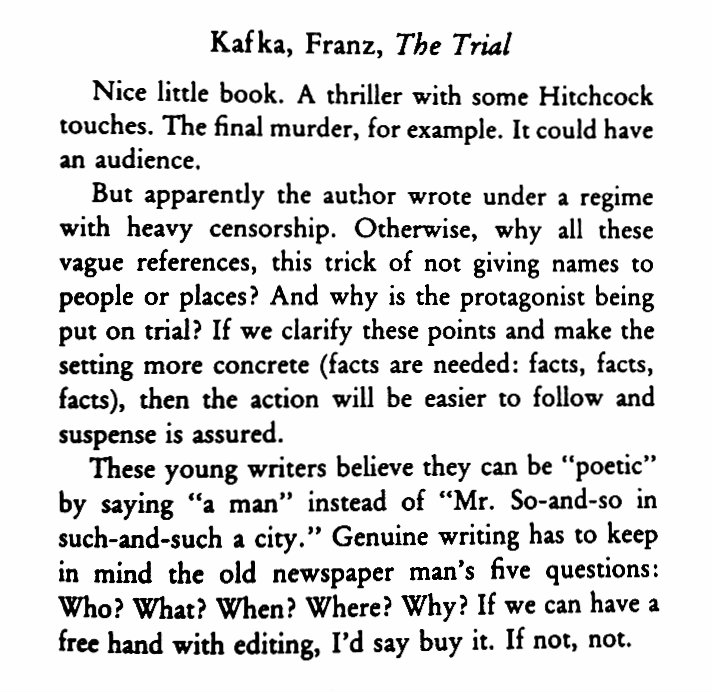

From “Regretfully We Are Returning Your…” by Umberto Eco. Published in Misreadings. English translation by William Weaver.

It has been said that fictional characters are underdetermined that is, we know only a few of their properties while real individuals are completely determined, and we should be able to predicate of them each of their known attributes. But although this is true from an ontological point of view, from an epistemological one it is exactly the opposite: nobody can assert all the properties of a given individual or of a given species, which are potentially infinite, while the properties of fictional characters are severely limited by the narrative text and only those attributes mentioned by the text count for the identification of the character.

In fact, I know Leopold Bloom better than I know my own father. Who can say how many episodes of my father’s life are unknown to me, how many thoughts my father never disclosed, how many times he concealed his sorrows, his quandaries, his weaknesses? Now that he is gone, I shall probably never discover those secret and perhaps fundamental aspects of his being. Like the historians described by Dumas, I muse and muse in vain about that dear ghost, lost to me forever. In contrast, I know everything about Leopold Bloom that I need to know—and each time I reread Ulysses I discover something more about him.

From Umberto Eco’s essay “Some Remarks on Fictional Characters,” collected in Confessions of a Young Novelist.

Let’s start with some facts:

Nanni Balestrini originally composed Tristano in the 1960s with the aid of an algorithm supplied to an IBM computer.

There are ten chapters in the novel.

Each chapter is comprised of twenty paragraphs.

Balestrini’s algorithm shuffles fifteen of those paragraphs within each chapter.

There are thus 109,027,350,432,000 possible versions of Tristano.

Tristano was published in 1966 by the Italian press Feltrinelli, but in only one of those 109,027,350,432,000 possible versions.

Now, Verso Books has published 4,000 different versions of Tristano in English.

They sent me #10786 to review.

Maybe a few more facts, and then some opinions—and citations from the novel—no?

Umberto Eco spends the first five pages of his six page introduction to Tristano situating Balestrini’s project in its proper literary-historical context. (He names some names: Pascal, Georg Philipp Harsdörffer, Christopher Clavius, Pierre Guldin, Mersenne, Leibniz, Borges, Queneau, Mallarmé, Manzoni, Joyce. There is no mention of Cortázar’s Hopscotch or Bantam’s Choose Your Own Adventure series).

Mike Harakis translated Tristano into English.

Harakis preserves Balestrini’s spare (and often confusing) style of punctuation.

The book is exactly 120 pages.

In his contemporary “Note on the Text” of Tristano, Balestrini says that the book is “an ironic homage to the archetype of the love story.”

The title of course alludes to the legend of Tristan and Iseult.

In his note, Balestrini uses the term “experiment” at least three times, suggesting that “to experiment with a new way of conceiving literature and novels” can make it more “possible to represent effectively the complexities and unpredictability of contemporary reality.”

Balestrini’s 2004 novel Sandokan is in my estimation one of the finest books of the past decade: A poetic examination of criminal brutality told in a bold voice, its syntactical experiments not experiments at all, but rather the base of a strong, strange tone that perfectly synthesizes plot and voice.

Okay. Opinions and citations:

In chapter 2 of my edition of Tristano—on page 19 of version #10786—we get a paragraph that begins: “To be one-sided means not to look at problems all-sidedly.”

Does Tristano, through its formal, discursive, algorithmic structure seek to approach an all-sided perspective? Significantly, we can’t be sure who says the line. There are two characters, male and female, both named C (an algebraic variable?).

There seems to be an argument here, an investigation. A crime, a love affair. But Tristano is a dialectic without synthesis. Or maybe that failure is mine. Maybe I’ve failed as the reader. Neglected my part. “Treat life as if it were a game,” we’re told in the aforementioned paragraph (page 19 of version #10786, if you’re keeping score). Or maybe we’re not told. Maybe C is telling C to treat life as a game (and not just telling the reader), but the context is not (cannot) be clear.

But again, that’s probably maybe almost certainly but okay maybe not quite the point of Tristano. From paragraph 18 of chapter 6 (page 71 of version #10786): “First of all one must have a fairly clear idea of the content of the text.” And a few lines down: “Her story weaves and unweaves like the tapestry she was working on.” And: “It’s the unconditional loss of language that starts.” And: “It might never have an end.” Freeing these lines from the sentences around them ironically stabilizes them.

Tristano isn’t just line after line of Postmodernism 101 though. There is actual imagery here, content. In fairness, let me share entire paragraph (from page 69 of version #10786):

In the internal part of the cave along with an abundance of Pleistocene fauna a human Neanderthaloid tooth was recovered. You’ve already told me this story. The cave is divided into two levels one upper and one lower that host a subterranean lake which can be visited by boat. It might even be another story. They had warned him it wouldn’t be a walk in the park. Inside you can go down into a great cavern in the centre of which there is a rock surmounted by a giant stalagmite. We’ll stay and look for another thirty seconds then we’ll leave. All the stories are different one from the other. On returning he found that C had bought herself a new blue silk dress. C remained standing while he explained to her how it had gone. She ran a finger over his lips to wipe the lipstick off them. I have to go. It’s still early. I’ll be away all day perhaps tomorrow too. He gave her a long kiss on the lips.

This paragraph is maybe almost kind of sort of a synecdoche of the entire book—sentences that seem to belong to other paragraphs, story threads that seem part of another tapestry. Let us pull a thread from another paragraph, another chapter (chapter 9, paragaph 8, page 102 of of version #10786):

All imaginable pathways of the line that represents a direct connexion to the objective are equally impracticable and no adjustment of the shape of the body to the spatial forms of the surrounding objects can allow the objective to be reached.

Do you believe that? Did Balestrini? Or did it just allow him a neat little piece of rhetoric to gel with the concept of his experiment? The verbal force, dexterity, and dare I claim truth of Sandokan, composed a few decades later, suggests that yes, language can be shaped to mean.

And this, I think, is the big failure of Tristano—it’s a text afraid to mean, to even take a shot at meaning. Content to be simply an experiment, its sections adding up to nothing more than the suggestion that its sections could never add up to anything, Tristano offers little beyond its concept and a few observations on storytelling that dwell on paralysis instead of freedom. The whole experiment strikes me as the set up for a joke played on the reader: Look at all this possibility, look at all these iterations—and what’s at the core? Nothing.

I hate to end on such a negative note. I’m thankful that Verso published Tristano, which I think shows courage as well as a commitment to literature that you just aren’t going to see from a corporate house. I’m thankful that I got to read (version #10786 of) Tristano, and I plan to order his novel The Unseen via my local bookstore. The expectations that I brought to the book were huge: Loved the concept, loved the last book I’d read by the author—and I want to read more by the author. Indeed, it’s entirely possible that I failed Tristano’s experiment. But I would’ve been happier to learn something or feel something from that failure other than disappointment.

I’m just two chapters shy of finishing Nanni Balestrini’s Tristano—I’ve kind of lax about these “book acquired” posts lately—so full review forthcoming. But here’s the blurb:

This book is unique as no other novel can claim to be: one of 109,027,350,432,000 possible variations of the same work of fiction.

Inspired by the legend of Tristan and Isolde, Tristano was first published in 1966 in Italian. But only recently has digital technology made it possible to realise the author’s original vision. The novel comprises ten chapters, and the fifteen pairs of paragraphs in each of these are shuffled anew for each published copy. No two versions are the same. The random variations between copies enact the variegations of the human heart, as exemplified by the lovers at the centre of the story.

The copies of the English translation of Tristano are individually numbered, starting from 10,000 (running sequentially from the Italian and German editions). Included is a foreword by Umberto Eco explaining how Balestrini’s experiment with the physical medium of the novel demonstrates ‘that originality and creativity are nothing more than the chance handling of a combination’.

I’ll write a proper review in the next week or two, but the quick version is that This Is Not for Everyone, but you can probably already tell that from the blurb, right? The prose is also Not for Everyone, which is what I suspect most people who come to Tristano, interested in the concept, will be most disappointed in. Balestrini isn’t delivering a plot driven story that “recombines” into new versions for the reader. This is something closer to Donald Barthelme’s disruptions and displacements—poetic, strange, occasionally funny, moving.

When people in their fifties sit down before their television sets for a rerun of Casablanca, it is an ordinary matter of nostalgia. However, when the film is shown in American universities, the boys and girls greet each scene and canonical line of dialogue (“Round up the usual suspects,” “Was that cannon fire, or is it my heart pounding?”–or even every time that Bogey says “kid”) with ovations usually reserved for football games. And I have seen the youthful audience in an Italian art cinema react in the same way. What then is the fascination of Casablanca?

The question is a legitimate one, for aesthetically speaking (or by any strict critical standards) Casablanca is a very mediocre film. It is a comic strip, a hotch-potch, low on psychological credibility, and with little continuity in its dramatic effects. And we know the reason for this: The film was made up as the shooting went along, and it was not until the last moment that the director and script writer knew whether Ilse would leave with Victor or with Rick. So all those moments of inspired direction that wring bursts of applause for their unexpected boldness actually represent decisions taken out of desperation. What then accounts for the success of this chain of accidents, a film that even today, seen for a second, third, or fourth time, draws forth the applause reserved for the operatic aria we love to hear repeated, or the enthusiasm we accord to an exciting discovery? There is a cast of formidable hams. But that is not enough.

Here are the romantic lovers–he bitter, she tender–but both have been seen to better advantage. And Casablanca is not Stagecoach, another film periodically revived. Stagecoach is a masterpiece in every respect. Every element is in its proper place, the characters are consistent from one moment to the next, and the plot (this too is important) comes from Maupassant–at least the first part of it. And so? So one is tempted to read Casablanca the way T. S. Eliot reread Hamlet. He attributed its fascination not to its being a successful work (actually he considered it one of Shakespeare’s less fortunate plays) but to something quite the opposite: Hamlet was the result of an unsuccessful fusion of several earlier Hamlets, one in which the theme was revenge (with madness as only a stratagem), and another whose theme was the crisis brought on by the mother’s sin, with the consequent discrepancy between Hamlet’s nervous excitation and the vagueness and implausibility of Gertrude’s crime. So critics and public alike find Hamlet beautiful because it is interesting, and believe it to be interesting because it is beautiful.

On a smaller scale, the same thing happened to Casablanca. Forced to improvise a plot, the authors mixed in a little of everything, and everything they chose came from a repertoire of the tried and true. When the choice of the tried and true is limited, the result is a trite or mass-produced film, or simply kitsch. But when the tried and true repertoire is used wholesale, the result is an architecture like Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia in Barcelona. There is a sense of dizziness, a stroke of brilliance. Continue reading ““Casablanca, or, the Clichés Are Having a Ball” — Umberto Eco”

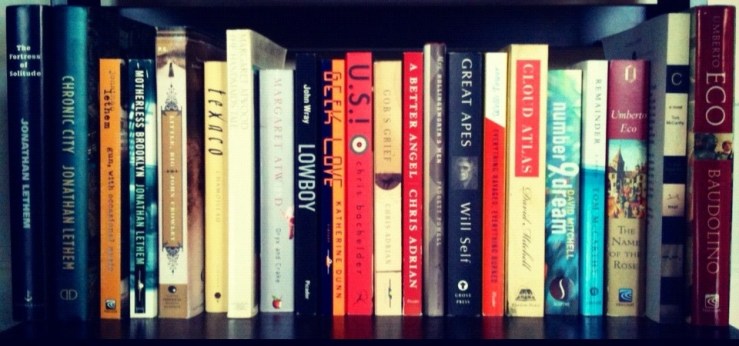

Book shelves series #14, fourteenth Sunday of 2012.

This is a strange shelf: it’s the bottom shelf of the ladder book shelf I’ve been photographing over the past few weeks, and it’s probably the least organized so far. There’s also a higher ratio of unread books on this shelf than in previous shelves. Anyway, left to right:

I was far more enthusiastic about Jonathan Lethem just a few years ago. I still think The Fortress of Solitude and Motherless Brooklyn hold up (they do in my memory, anyway), but Chronic City was awful (then why is it still on my shelf) and You Don’t Love Me Yet is one of the most pointless, silly, and gross books I’ve ever read.

I had good intentions to read John Crowley’s Little, Big and Patrick Chamoiseau’s Texaco and John Wray’s Lowboy and Katherine Dunn’s Geek Love: I’m actually pretty sure I got all these novels around the same time. They must have been in a stack that eventually got shelved here during a reshelving.

I’ve read at least five or six more Margaret Atwood novels than the ones here, but have no idea where they are (likely a combination of cheap mass markets that I gave to friends or lost).

Chris Bachelder’s U.S.! is an underread gem. Chris Adrian: Again, I was more enthusiastic about his work a few years ago, but I think it holds up. Also, would the person who borrowed my first edition hardback of The Children’s Hospital please return it? Padgett Powell’s slim novel is not bad.

Will Self’s Great Apes holds the distinction of being the ickiest novel I’ve ever read. Horrifying stuff. I bought it at an airport—in Bangkok? LA? Houston? I really can’t remember—I was returning to the US from Thailand and had bought the cheapest possible plane ticket—one that would basically keep me en route for three days, sleeping on planes and in airports. Anyway, Self’s nightmare book is bound up in that experience: it’s a riff on Kafka; dude wakes up to find that he’s become a chimp. It’s just so gross on so many levels. (Maybe I should add that I find seeing chimps dressed as humans to be the acme of perversion).

The Wells Tower collection is gold.

David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas is gold, but I never got past the first 20 pages of number9dream, which seemed to really bite from William Gibson. I loved both the Tom McCarthy books, particularly C. Eco’s The Name of the Rose is a bit overrated and Baudolino’s first half is not bad, but it just goes on and on and on . . . but it’s funny.

(From The Role of the Reader by Umberto Eco)

Let me get this out of my system:

In no particular order a list of stuff I wished I’d written about in 2011:

1. Renata Adler’s amazing novel-in-vignettes Speedboat.

2. Wittgenstein’s Mistress by David Markson. End of the world cultural riffage. No raffage.

3. The Stories of Breece D’J Pancake: soul-crashing sad. [Not a typo].

4. Season two of Boardwalk Empire: The Oedipal complex as a plot arc hasn’t been done so well since The Sopranos. Most HBO shows seem to be about capitalism and law (see also: Deadwood, The Wire, The Sopranos).

5. That first episode of Luck. I love David Milch. Michael Mann seems imminently capable of filming things (although I think Heat is overrated, even though it has Val Kilmer, and he’s radness in the form of a lion in the form of a sea lion). The opening episode was dry like vermouth. But I will watch, because of Deadwood.

6. Hung. My wife and I are the only two people in America who liked Hung. Then it got canceled.

7. Captain America: All of the shots + set design in this film seem to have been straight up stolen from the Star Wars films—except the shots that were stolen from the Indiana Jones films. It’s funny in a way because Lucas (and Spielberg) were stealing from old serial films that were contemporaneous with the age that Captain America is meant to be set in. (And, oh, yeah, the movie was contrived bullshit).

8. I wish I’d reviewed How to Keep Your Volkswagen Alive by Chris Boucher. It was new and fresh and strange and deserved a good review from this blog, but it was very difficult to write about. I tried. It’s simultaneously sad, funny, too-experimental, but also rich and rewarding. An excellent flawed début.

9. The Trip: Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon take a trip through Northern England, eating at Michelin starred inns, creeping on the wild misty moors, referencing plenty of Romantic lit, and riffing—and backbiting—a lot. Comedy + tragedy done right. Lovely.

10. The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai: Across the 8th Dimension: Okay, frankly, I was ashamed to admit that I hadn’t seen it until this summer. Batshit insane interstellar hi-jinks. Rasta aliens. Buckaroo and his men are in a band! The ending credits sequence is the second best I’ve ever seen (after Lynch’s closing credits for INLAND EMPIRE).

11. The last Harry Potter movie. It was good. I’m glad they’re over though.

12. Baudolino by Umberto Eco, which I listened to on mp3 while refinishing a room in my new house. The first half was great—silly, bawdy, funny—but it unraveled into a sloppy mess by the end.

13. The Hunger Games by whoever wrote The Hunger Games, I think her name is Suzanne Collins, but Christ I’m not gonna waste any time checking: I listened to this audiobook working on the same room project that I worked on while listening to Baudolino. Look, I get that these books are for kids, and that they’re probably a sight better than Twilight, but sheesh, exposition exposition exposition. There’s nothing wrong with letting readers fill in the gaps (especially when your book is ripping off The Running Man + a dozen other books). Also, there’s a character in this book who I think is named after pita bread.

14. A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller. Another audiobook that I listened to working on the aforementioned project—only this book is pure excellence, a post-apocalyptic examination of faith and meaning set against Big Nothing. The first third recalled Blood Meridian to me, although McCarthy’s book must have been composed 25 years after Miller’s.

15. I finally watched Party Down after all of my friends kept telling me, “You gotta watch Party Down!” Have you seen Party Down? You gotta watch Party Down!

16. Various short stories by Melville and Hawthorne: I read a lot of short pieces from these guys, mostly obscure, often half-baked stories that were still better than 99.9% of the contemporary stuff American writers are doing.

17. Uncreative Writing by Kenneth Goldsmith. Goldsmith is a hero: Ubuweb is magic. But a lot of Uncreative Writing just felt like an excuse for Goldsmith to share his favorite riffs on avant gardism from the classroom. And I know he’s probably a great and inspiring teacher, and I’m sure his Uncreative Writing class was gangbusters and meaningful for his students. Maybe it’s because I teach at a community college; maybe I’m conservative—I’m a fan of Dada; I get Walter Benjamin, blah blah blah. I just think we should cite sources still. Originality may be a fiction, but synthesis isn’t. Research and documentation are meaningful. Still, an entertaining book.

18. Music. Although most writing about music sucks.

19. Probably several dozen other books, movies, TV shows, etc. But there’s always 2012 to become overwhelmed by!

Happy New Year!

From a 2009 interview with Der Spiegel—

Umberto Eco: The list is the origin of culture. It’s part of the history of art and literature. What does culture want? To make infinity comprehensible. It also wants to create order — not always, but often. And how, as a human being, does one face infinity? How does one attempt to grasp the incomprehensible? Through lists, through catalogs, through collections in museums and through encyclopedias and dictionaries. There is an allure to enumerating how many women Don Giovanni slept with: It was 2,063, at least according to Mozart’s librettist, Lorenzo da Ponte. We also have completely practical lists — the shopping list, the will, the menu — that are also cultural achievements in their own right.

SPIEGEL: Should the cultured person be understood as a custodian looking to impose order on places where chaos prevails?

Eco: The list doesn’t destroy culture; it creates it. Wherever you look in cultural history, you will find lists. In fact, there is a dizzying array: lists of saints, armies and medicinal plants, or of treasures and book titles. Think of the nature collections of the 16th century. My novels, by the way, are full of lists.

SPIEGEL: Accountants make lists, but you also find them in the works of Homer, James Joyce and Thomas Mann.

Eco: Yes. But they, of course, aren’t accountants. In “Ulysses,” James Joyce describes how his protagonist, Leopold Bloom, opens his drawers and all the things he finds in them. I see this as a literary list, and it says a lot about Bloom. Or take Homer, for example. In the “Iliad,” he tries to convey an impression of the size of the Greek army. At first he uses similes: “As when some great forest fire is raging upon a mountain top and its light is seen afar, even so, as they marched, the gleam of their armour flashed up into the firmament of heaven.” But he isn’t satisfied. He cannot find the right metaphor, and so he begs the muses to help him. Then he hits upon the idea of naming many, many generals and their ships.

SPIEGEL: But, in doing so, doesn’t he stray from poetry?

Eco: At first, we think that a list is primitive and typical of very early cultures, which had no exact concept of the universe and were therefore limited to listing the characteristics they could name. But, in cultural history, the list has prevailed over and over again. It is by no means merely an expression of primitive cultures. A very clear image of the universe existed in the Middle Ages, and there were lists. A new worldview based on astronomy predominated in the Renaissance and the Baroque era. And there were lists. And the list is certainly prevalent in the postmodern age. It has an irresistible magic.