Let me start by erasing my own anxieties about “reviewing” The Last Jedi (2017, dir. Rian Johnson). I saw it over a month ago in a packed theater with my wife and two young children. We loved it. I haven’t seen it since then, although I’d like to. Because I’ve only seen it once, this “review” will be far lighter on specific illustrating examples than it should be. Now, with some of those (writing) anxieties dispersed, if not exactly erased:

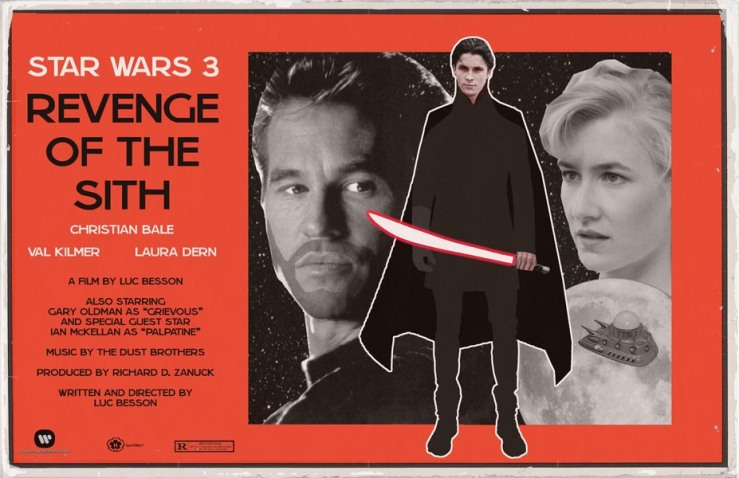

The Last Jedi strikes me as one of the best Star Wars films to date, of a piece with The Empire Strikes Back (1980, dir. Irvin Kershner) and Revenge of the Sith (2005, dir. George Lucas).

Not everyone agrees with me. Clearly, a lot of people hated Rian Johnson’s take on Star Wars. I won’t repeat the laundry list of gripes about The Last Jedi, but instead offer this: the numerous noisy denunciations of The Last Jedi can be rebutted via the terms, tropes, and tones of any of the previous films themselves. Put another way, anything “wrong” (tone choices, plot devices, casting, etc.) with The Last Jedi can be found to be “wrong” with any of the previous films. Furthermore, I don’t intend to directly rebut gripes about The Last Jedi here. Most attacks on the film simply amount to iterations of, “This film did not do what I wanted this film to do,” to which my reply would be, “Well, good.”

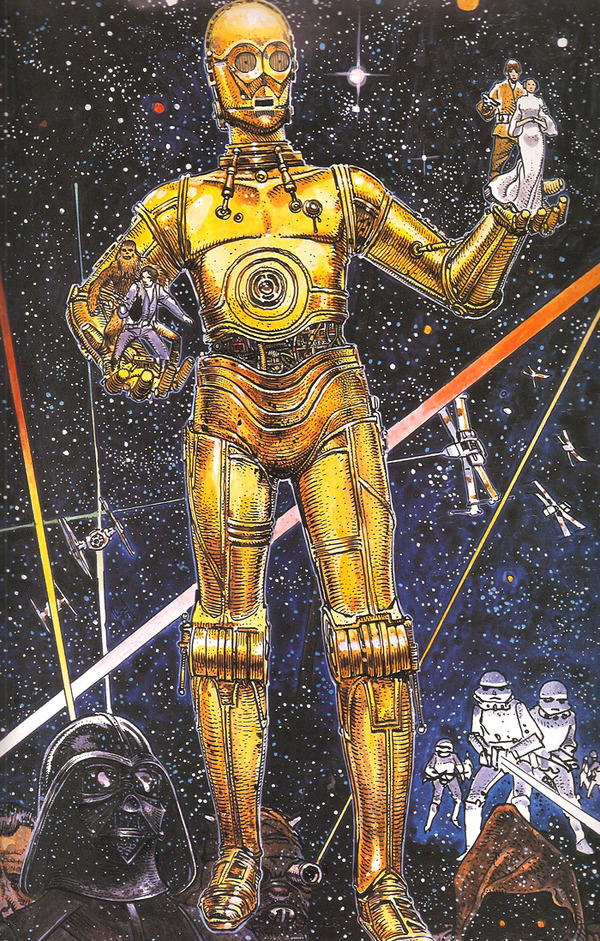

“Well, good” — the passionate reactions to The Last Jedi show the film’s power—both narratively and more importantly, aesthetically—to disturb a cultural sense of what the Star Wars franchise “is” or “is not.” In burning down much of the mythos (again, both narratively and aesthetically) of the films that preceded it, The Last Jedi opens up new space for the series to grow.

I enjoyed The Last Jedi’s most immediate predecessor, The Force Awakens (2015, dir. J.J. Abrams), but was critical of its inability to generate anything truly new. Riffing on The Force Awakens, I wrote that the film “is a fun entertainment that achieves its goals, one of which is not to transcend the confines of its brand-mythos. . . [the film] takes Star Wars itself (as brand-mythos) as its central subject. The film is ‘about’ Star Wars.” And, more to the point:

Isn’t there a part of us…that wants something more than the feeling of (the feeling of) a Star Wars film? That wants something transcendent—something beyond that which we have felt and can name? Something that we don’t know that we want because we haven’t felt it before?

The Last Jedi transcends the narrative stasis of The Force Awakens. “Stasis” is probably not a fair word to describe TFA. Abrams’s film excited viewers, roused emotions, offered engaging new characters, and even killed off a classic character via the classic Star Wars trope of Oedipal anxiety erupting in violent rage. TFA’s stasis is the static-but-not-stagnant excitement of having expectations confirmed. In contrast, Rian Johnson’s The Last Jedi punctures viewer expectations at almost every opportunity, aesthetically restaging tropes familiar to the series but then spinning them out in new, unforeseen directions.

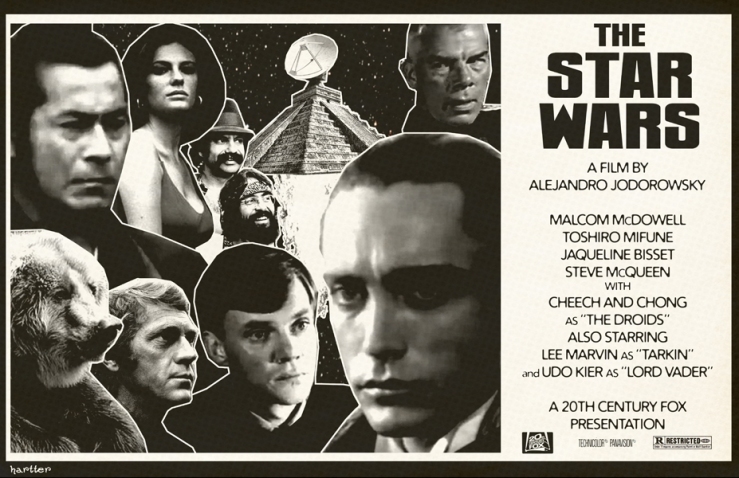

The Last Jedi echoes visual tropes from The Empire Strikes Back in particular. Indeed, many fans believed that Rian Johnson’s TLJ would (or even should) reinterpret Irvin Kershner and Lawrence Kasdan’s entry into the series, much as J.J. Abrams had restaged A New Hope (1977, dir. George Lucas) with The Force Awakens. Instead, Johnson pushes the Star Wars narrative into new territory, with an often playful (and sometimes absurd) glee that has clearly upset many fans.

Johnson’s (successful) attempt to reinvent Star Wars might best be understood in terms of what the literary critic Harold Bloom has called the anxiety of influence. Bloom uses the anxiety of influence to describe an artist’s intense unease with all strong precursors. To succeed, new artists must overcome their aesthetic progenitors. Bloom compares the anxiety of influence to the Oedipal complex. An artist has to symbolically kill what has come before in order to thrive.

An apt description of franchise filmmaking’s inherent anxiety of influence can be found in Dan Hassler-Forest’s essay “The Last Jedi: Saving Star Wars from Itself,” published last year in the Los Angeles Review of Books:

An overwhelming anxiety of influence predictably permeates any new director’s attempt to elaborate on the world’s most famous entertainment franchise. In J. J. Abrams’s hands, this anxiety was clearly that of a fan-producer struggling to meet other fans’ expectations while also establishing a viable template for future installments. In doing so, his cinematic points of reference never seemed to extend far beyond the Spielberg-Lucas brand of Hollywood blockbusters that shaped his generation of geek directors, and he tried desperately to make up for what he lacks in auteurist vision with energy, self-deprecating humor, and generous doses of fan service.

But Rian Johnson is a filmmaker of an entirely different caliber. Just as Irvin Kershner and Lawrence Kasdan once added complexity, wit, and elegance to Lucas’s childish world of spaceships and laser swords, Johnson makes his whole film revolve around characters’ fear of repeating the past, and both the attraction and the risk of breaking away from tradition.

A break with any tradition, however, paradoxically confirms the power of that tradition. Johnson understands and clearly respects the Star Wars tradition. Despite what his detractors may believe, Johnson hasn’t erased or trampled upon the Star Wars mythos in The Last Jedi; rather, as the Modernist manifesto commanded, he’s made it new. Continue reading “The Last Jedi and the Anxiety of Influence”

So moving. Read the whole story.

So moving. Read the whole story.