I didn’t really read that many new books—by which I mean books published in 2012—this year.

The highlight of the new books I did read was Chris Ware’s Building Stories, the moving story of the lives of several people (and a bee!) who live in the titular building (and other places. And other buildings. Look, it’s difficult to describe). Building Stories is a strange loop, a collection of 14+ elements (the big box it comes in is part of the puzzle) that allows the reader to reconstruct the narratives in different layers.

I also really dug the second installment of Charles Burns’s trilogy, The Hive; Burns and Ware are two of the most talented American writers working right now, suggesting that some of the most exciting stuff happening in American literature is happening in comic books.

Speaking of second installments in ongoing trilogies, I also listened to Hilary Mantel’s Bring Up the Bodies, which I liked, and read Lars Iyer’s Dogma and liked it as well—sort of like Beavis & Butthead Do America by way of Samuel Beckett.

I read Dogma at the beach the same week I read Michel Houellebecq’s The Map & The Territory, an uneven but engaging novel about art; the novel eventuually shifts into a strange murder procedural before exploring a fascinating vision of what a post-consumer future might look like. I dig Houellebecq and look forward to whatever he’ll spring on us next.

Another strange book I liked very much was Phi by Giulio Tononi, an exploration of consciousness written as a kind of Dante’s Inferno of the brain. A beautiful and perhaps overlooked book of 2012.

Indie presses in general tend to get overlooked—not in the sense that their books don’t have a community of readers, but in that their books don’t always reach the wider audience they deserve. I liked new books this year by Matt Bell (Cataclysm Baby), Matt Mullins (Three Ways of the Saw), and Jared Yates Sexton (An End to All Things). These books are all very different in style and content, but all marked by precise, unpretentious writing. Good stuff.

Like I said though, I didn’t read that many books published in 2012—even when I intended to. Like George Szirtes’s English translation of László Krasznahorkai’s novel Satantango, for instance. I was right in the middle of something when I got my review copy, and by the time I started it the hype surrounding it was almost unbearable—the sort of palate-clouding noise (to mix and misuse metaphors) that deafens a fair reading. (To be clear: I blame myself. I could easily refrain from Twitter and quit following lit news online). By the time Hari Kunzru documented the hype in a mean-spirited (but hilarious) article forThe Guardian, I knew I’d have to set Satantango aside for a bit. It’s worth noting here that Hari Kunzru’s own novel Gods without Men had been lingering in my to read stack for some time at that point, but his Satantango article managed to get it shelved. Still, I’m interested in reading it—maybe sometime late next year.

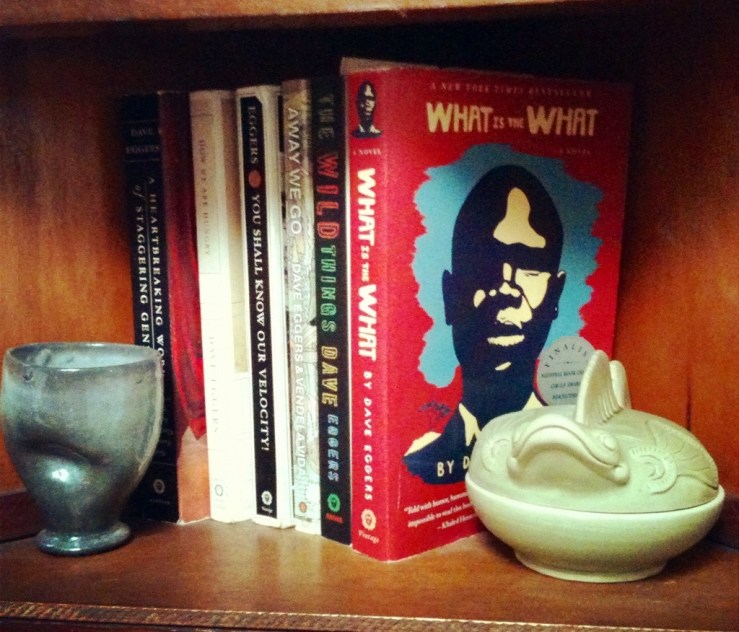

There were plenty of top listed writers who put out books this year that I probably would’ve been excited to read six or seven years ago or at least feel obligated to read and write about two or three years ago. But by 2012 I just don’t care anymore. At the risk of sounding overly dismissive (not my intention), I just can’t make time for another middling Michael Chabon novel, or another bloated tome from Zadie Smith, or another empty exercise in style from Junot Diaz, or another whatever from Dave Eggers.

Most of the great new stuff I read in 2012 was really just playing catch up to 2011—I loved Teju Cole’s Open City, found Nicholson Baker’s House of Holes to be an amusing diversion, and declared Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams a perfect novella. I also read Adam Johnson’s The Orphan Master’s Son, and used it, along with Jeffrey Eugenides’s The Marriage Plot as a kind of springboard to discuss lit criticism (which everyone in my particular echo chamber wanted to spar about this year) and what I want from books these days.

Two books I pretty much hated: Joshua Cody’s clever but empty memoir [sic] and Alain de Botton’s facile self-help book Religion for Atheists.

On the whole though, most of what I read in 2012 was fantastic and most of what I read in 2012 was published before 2012.

The major highlight of the year was finally reading William Gaddis’s novels The Recognitions and J R. I also read Gaddis’s posthumous novella AgapēAgape, an erudite rant that purposefully echoes the work of Thomas Bernhard, another cult writer I finally got to in 2012. His novels Correction and The Loser challenged me, made me laugh, and occasionally disturbed me.

And while I’m on Bernhard, perhaps I should squeeze in the collection I read by one of his predecessors, Robert Walser, and the poetry collection (After Nature) I read by one of his followers, W.G. Sebald. Both were excellent. And while I’m squeezing stuff in—or perhaps showing how writers lead me to read other writers—I’ll admit that I hadn’t read Thomas Browne’s Urn Burial (referenced heavily in Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn) until this year.

Another book that I finally got to this year that blew me away was John Williams’s lucid and sad novel Stoner. Reading Stoner, produced one of those can’t-believe-I-haven’t-read-it-before moments, which I experienced again even more intensely with Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman, a surreal comic masterpiece which may be the best book I read in 2012. I also finally read—and was blown away by—Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (why had I not read it yet? Maybe I read it before. Not sure. In any case, if I did read it before it’s clear to me that I didn’t really read it). I took another shot at Marcel Proust but it didn’t take. Again.

Clarice Lispector received some much-deserved attention from the English-speaking world this year when New Directions released four new translations of her work. I found her novella The Hour of the Star sad, funny, and captivating. Also on the novellas-by-South-Americans: I’m working my ways through Alvaro Mutis’s Maqroll novellas and they are fantastic.

I also finally got to David Markson’s so-called “note card novels,” devouring them in a quick stretch. I reviewed the last one, The Last Novel.Markson’s novels are often called “experimental,” a term I kind of hate, but perhaps serves as easy tag for many of the novels I enjoyed best this year, including Ben Marcus’s The Age of Wire and String and Barry Hannah’s hilarious tragedy Hey Jack!

Hey, did you know David Foster Wallace wrote an essay on David Markson? The previous sentence is an extremely weak attempt to transition to Both Flesh and Not, a spotty collection from the late great writer; it showcases some brilliant moments along with undercooked material and a few throwaways probably better left uncollected. I fretted about the book on Election Night.

The posthumous book mill also kept pumping out stuff from Roberto Bolaño, including an unfinished novel called The Woes of the True Policeman that seems like a practice sketch for 2666 (I haven’t read Woes and don’t feel particularly compelled to). I did read and enjoy The Secret of Evil, a book that might not be exactly essential but nevertheless contains some pieces that further expand (and darken and complicate) the Bolañoverse. Going back to that Bolañoverse was a highlight of the year for me—rereading 2666proved to be tremendously rewarding, yielding all kinds of new grotesque insights. I also reread The Savage Detectives, and while it’s hardly my favorite by RB, I got more out of it this time.

I also revisited The Hobbit this year and somehow decided it’s a picaresque novel. Definitely a picaresque: Blood Meridian, which I reread as well. In fact, I’ve reread it at least once a year since the first time I read it, and it gets funnier and richer and more devastating with each turn. I also reread Herman Melville’s “Bartleby” and tried to make sense out of it. I will reread Moby-Dick next year, although it’s not “Bartleby” that sparked the desire—chalk it up to Charles Olson’s amazing study Call Me Ishmael.

Olson’s study reminds me to bring up some of the nonfiction I enjoyed this year: Stephen Bronner’s Modernism at the Barricades, Robert Hughes’s Goya biography, the parts of William T. Vollmann’s Imperial that I read, Patti Smith’s memoir Just Kids,and big chunks of William Gass’s collection Finding a Form.

Perhaps the most significant change in my reading habits this year was embracing an e-reader. I got a Kindle Fire for Christmas last year and wound up reading from it—a lot. About half the books I read this year I read on the Kindle. I also read lots of comics on it with my daughter, including all of Jeff Smith’s Bone, much of Tintin, and all of Carl Barks’s Donald Duck stuff. (I also read several hard to find volumes from Moebius via the Kindle).

And while I love my Kindle and it’s become my go-to for night reading (it’s lightweight and self-illuminating), I can’t see it replacing physical books. To return to where I started: Chris Ware’s Building Stories, an innovative, sprawling delight simply would not be reproducible in electronic form. Ware’s book (if it is a book (which it is)) reminds us that the aesthetics of reading—of the actual physical process of reading—can be tremendously rewarding as a tactile, messy, sprawling experience.

Perhaps because I’ve freed myself from the anxiety of trying to write on this blog about everything that I read, and perhaps because I’ve freed myself from trying to write traditional reviews on this blog, and perhaps because I’ve freed myself from trying to cover contemporary literary fiction on this blog—perhaps because of all of this, I’ve enjoyed reading more this year than I can remember ever having enjoyed it before.

It’s sort of like those kids who had pet monkeys when you were in elementary school, always someone’s cousin, or their neighbor’s friend from another school; sometimes the story was accompanied by a thumbprint-smudged Polaroid of the creature, clutching lovingly to some human torso. But did you ever actually see it? No never. Not once. And anyone who says they did is part of the conspiracy. Sure, maybe somewhere in Mexico someone has a monkey for a pet, but not here, no way, and certainly not your cousin. And look, I agree that it’s a weird thing to lie about, but that’s part of what makes good liars good, it’s some sort of weird emotional long-con that you are complicit in by listening to them.

It’s sort of like those kids who had pet monkeys when you were in elementary school, always someone’s cousin, or their neighbor’s friend from another school; sometimes the story was accompanied by a thumbprint-smudged Polaroid of the creature, clutching lovingly to some human torso. But did you ever actually see it? No never. Not once. And anyone who says they did is part of the conspiracy. Sure, maybe somewhere in Mexico someone has a monkey for a pet, but not here, no way, and certainly not your cousin. And look, I agree that it’s a weird thing to lie about, but that’s part of what makes good liars good, it’s some sort of weird emotional long-con that you are complicit in by listening to them. So, I’m thinking this thing goes deep, deeper than any of us ever imagined. Obviously Dave Eggers is involved somehow, either as the mastermind behind the whole thing, or just another pawn like the rest of us. I emailed Mr. Heartbreaking Jerk himself, asking if even he of all people can claim to have actually read all of Rising Up and Rising Down, and in return I received an auto-reply, something about the volume of emails he receives blah blah blah—the point is I think I scared him, and now I know I’m on the right trail . . .

So, I’m thinking this thing goes deep, deeper than any of us ever imagined. Obviously Dave Eggers is involved somehow, either as the mastermind behind the whole thing, or just another pawn like the rest of us. I emailed Mr. Heartbreaking Jerk himself, asking if even he of all people can claim to have actually read all of Rising Up and Rising Down, and in return I received an auto-reply, something about the volume of emails he receives blah blah blah—the point is I think I scared him, and now I know I’m on the right trail . . .

Sylvia Beach was the nexus point for Modernist and ex-pat literature for much of the first half of the twentieth century, running the Left Bank bookstore Shakespeare & Company until the Nazi occupation of Paris in 1941. She was the first publisher of Joyce’s Ulysses, she translated Paul Valéry into English, and was close friends to a good many great writers, including William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound, H.D., and Ernest Hemingway. In The Letters of Sylvia Beach, editor Keri Walsh compiles many of Beach’s letters from 1901 to just before her death in 1962. Framed by a concise biographical introduction and a useful glossary of correspondents, Letters reveals private insights into a fascinating literary period. There’s a sweetness to Beach’s letters, whether she’s inviting the Fitzgeralds to come to a dinner party or asking Richard Wright (“Dick”) how much he thinks a fair price for a record player is. The Letters of Sylvia Beach is out now from

Sylvia Beach was the nexus point for Modernist and ex-pat literature for much of the first half of the twentieth century, running the Left Bank bookstore Shakespeare & Company until the Nazi occupation of Paris in 1941. She was the first publisher of Joyce’s Ulysses, she translated Paul Valéry into English, and was close friends to a good many great writers, including William Carlos Williams, Ezra Pound, H.D., and Ernest Hemingway. In The Letters of Sylvia Beach, editor Keri Walsh compiles many of Beach’s letters from 1901 to just before her death in 1962. Framed by a concise biographical introduction and a useful glossary of correspondents, Letters reveals private insights into a fascinating literary period. There’s a sweetness to Beach’s letters, whether she’s inviting the Fitzgeralds to come to a dinner party or asking Richard Wright (“Dick”) how much he thinks a fair price for a record player is. The Letters of Sylvia Beach is out now from  I’m a couple of chapters into William T. Vollmann’s 1993 novel Butterfly Stories, one of his (three? four? Dude’s prolific) books about prostitution. The bullied butterfly grows up to be a boy who wants to be a journalist and then a journalist/inept sex tourist in southeast Asia. Good stuff. Here’s a mordantly elegant passage:

I’m a couple of chapters into William T. Vollmann’s 1993 novel Butterfly Stories, one of his (three? four? Dude’s prolific) books about prostitution. The bullied butterfly grows up to be a boy who wants to be a journalist and then a journalist/inept sex tourist in southeast Asia. Good stuff. Here’s a mordantly elegant passage: Been working through my reader’s copy of Dave Eggers’s The Wild Things, new in trade paperback from Vintage. I’m having a hard time envisioning a kind of review of the book that escapes the context of the book; that it’s a novelization of a movie script of a Maurice Sendak book of maybe a few dozen words. I loved that book growing up, so no reason that it should be adapted into a feature film, but hoped for the best due to Eggers’s involvement and the fact that the incomparable Spike Jonze was at the rudder. Or helm. Or whatever naval metaphor you wish. Anyway, I absolutely hated the movie–it was mostly melancholy and downright depressing at times. Whereas Sendak’s book channels the joys of transgressive energy while reiterating the need for stable familial order, Jonze’s movie was all sorrow and loss, the hangover of youth, each ecstasy overshadowed in darkness. Too much yin, not enough yang. Anyway. I’ll try to give the book its proper, fair due on its own terms without all that baggage. Full review forthcoming.

Been working through my reader’s copy of Dave Eggers’s The Wild Things, new in trade paperback from Vintage. I’m having a hard time envisioning a kind of review of the book that escapes the context of the book; that it’s a novelization of a movie script of a Maurice Sendak book of maybe a few dozen words. I loved that book growing up, so no reason that it should be adapted into a feature film, but hoped for the best due to Eggers’s involvement and the fact that the incomparable Spike Jonze was at the rudder. Or helm. Or whatever naval metaphor you wish. Anyway, I absolutely hated the movie–it was mostly melancholy and downright depressing at times. Whereas Sendak’s book channels the joys of transgressive energy while reiterating the need for stable familial order, Jonze’s movie was all sorrow and loss, the hangover of youth, each ecstasy overshadowed in darkness. Too much yin, not enough yang. Anyway. I’ll try to give the book its proper, fair due on its own terms without all that baggage. Full review forthcoming.