Do you know about the Oedipal complex? That Freudian thing? Of course you do. But if for some reason you don’t, or need a refresher, here’s a quick summary from one of my all time favorite lyricists, David Byrne: “Mom and Pop / They will fuck you up / For sure.” That joyful nugget is from one of the last songs Talking Heads recorded, “Sax and Violins,” a great little piece on modern life that is far more entertaining (and much shorter) than Jonathan Franzen’s over-hyped new novel Freedom.

Freedom works hard to prove that Mom and Pop will fuck you up. Your family will fuck you up. Then you will fuck up your own kids. Franzen’s (boring, oh my god are they boring) characters seem bound to play out repeated variations of the Oedipal complex. Furthermore, according to Freedom, our extra-familial relationships are merely substitutions or recapitulations of our own Oedipal family dramas. Even worse, Franzen seems to suggest in Freedom that all our ideologies, our passions, our beliefs are really just formed by our “morbidly competitive” impulses, impulses born in our fucked-up, Oedipal families. (“Morbidly competitive,” by the way, is Franzen’s term).

The novel centers on one family, the Berglunds, a perfectly normal (in the upper-middle-class-white-educated sense of “perfectly normal”) fucked up family of four. I’m dispassionate about this novel, so I’ll just lazily crib a short summary from a well-written piece I’m largely simpatico with, Ruth Franklin’s review at TNR—

Freedom takes place over a period of about thirty years, but its primary focus is on the George W. Bush era. When it begins, Patty and Walter Berglund, college sweethearts, are among the first wave of urban pioneers putting the gentry back into gentrification, fixing up a house in a blighted area of St. Paul that they will soon populate with their two children. The short preamble offers an overview of their lives from the perspective of their neighbors, from the time they move in as a young couple to their departure around the time the children leave for college. Patty, a former college basketball star who once made “second-team all-American,” is a mother and housewife in the newly popular liberal model: “tall, ponytailed, absurdly young, pushing a stroller past stripped cars and broken beer bottles and barfed-upon old snow. . . . Ahead of her, an afternoon of public radio, the Silver Palate Cookbook, cloth diapers, drywall compound, and latex paint; and then Goodnight Moon, then zinfandel.” She bakes cookies for the neighbors on their birthdays and opens her house to their children. But Patty’s baking and mothering cannot keep her home together: her son Joey, while still in high school, moves out to live down the street with his girlfriend Connie and her family, which happens to include the only Republican on the block. The strain that their child’s defection places on the Berglunds’ marriage is obvious to all. When they leave in the early 2000s for Washington, where Walter has a new job doing something vaguely ominous involving the coal industry, one of the neighbors remarks, “I don’t think they’ve figured out yet how to live.”

This overture sets the stage for the rest of the book, which begins and more or less ends with a ridiculously well-written journal by Patty. Patty (who is somehow a more-than-competent novelist despite having no training) allows the audience to witness her marriage crumbling from her perspective; we are also supposed to sympathize with her because her own childhood was fucked up by her family. Also, she was date-raped, a manipulative detail that adds little to the narrative (I’d call it Nice Writing at its worst). Patty’s seemingly interminable journal eventually gives way to shorter chapters focusing on Joey and Walter. There’s also Patty and Walter’s lifelong friend, ex-punk/would-be indie rock star Richard Katz. Much of the novel revolves around Patty’s desire for Richard and Walter’s desire for Richard (no homo) and Richard’s desire for what he thinks Walter and Patty have and Walter’s desire to be desired by Patty the way that Patty desires Richard and blah blah blah. It’s one big boring circle of “morbidly competitive” Oedipal tension. Franzen spends most of his time expounding on how each character feels about how another character feels about him or her in an endless solipsistic chain that fails to enlighten or even amuse. Too much telling, not enough showing.

Freedom threatens to become interesting when it picks up the Walter narrative. Walter, a die-hard environmentalist oozing oodles of liberal guilt, is hard at work with a bevy of über-Republicans and defense contractors and Texas oil men to save the planet. Via the novel’s ever-present free indirect style, Walter goes to great, finicky pains to explain how working with these creeps will actually, like, save the ecosystem. Hey, doesn’t “eco” come from the Greek “oikos,” meaning “house”? Why yes it does! Must be some kind of parallel there–save the planet, save your house, save your fucked up family . . . Only none of that pans out; instead the section gets bogged down in a cluster of details that mingle with Walter’s increasing attraction (no, deep love and lust) for his twenty-something assistant. Meanwhile, his son Joey is growing up all wrong and fucked up, falling in with neocons who hide their war profiteering in a cloak of patriotic ideology. The democratic freedom we think we cherish is a lie; the personal freedoms we struggle to obtain–by escaping our fucked-up families–is ultimately a damning, soul-devouring curse. The American Dream is just morbid competitiveness.

If Franzen intended to write a zeitgeist novel, a How We Live Now novel, I wonder if this is this really what he thinks the spirit of our age boils down to? He gets many of the details of the last decade right, but the prose is bloodless and the characters are dull, unlikable, and unsympathetic. Of course, real people can be dull, unlikable, and unsympathetic, but that usually means that we don’t want to hang out with them, let alone read about their fears and desires for almost 600 pages. If our own families are dull, at least they are usually likable and sympathetic–at least to us, anyway (I love and like my family, in any case). Freedom feels like a novel with nothing at stake, or, perhaps, a novel where everything has already been lost, where outcomes are drawn null and void from the outset. And really, I wouldn’t mind all of that if it wasn’t so tedious. It practically buckles under its own sense of weighted importance in trying to reveal how Oedipal tension underwrites ideology. Oedipus might have been fated from the get-go, but at least there was some action and excitement in his story–some level of heroism, anyway. And because I’ve brought up Oedipus again, I’ll indulge myself and cite Talking Heads one more time.

In “Once in a Lifetime,” probably the group’s most famous song, Byrne sings, “You may ask yourself / Well, how did I get here?” The song’s narrator wonders if he can escape time, wonders if his suburban confine is a trap or a paradise; there’s a sense of sublime ridiculousness to it all, as if he might transcend time and space and contemporary life and take off “Into the blue again /Into silent water.” He’s trying to navigate the weird gap between suburbia and ecology, between duty and freedom. It is a song that at once recognizes the existential despair of a modern, suburban life, comments on its absurdity, and then surpasses it heroically. The song is undeniably about a figure in crisis, but that figure decides that “Time isn’t holding us / Time isn’t after us.” That figure is freer than the characters in Freedom, and freer still in his weird warp of ambiguity (a warp concretely codified in Byrne’s bizarre dance in the video). The hero of “Once in a Lifetime” transmutes existential absurdity into sound and vision; Oedipus saves his country (and provides the audience with catharsis) via his ironic, tragic self-mutilation; Patty and Walter kiss and make up. It’s a dreadfully facile ending, the worst kind of wish-fulfillment that seems wholly unsupported by the narrative preceding it.

But perhaps this is an unfair way to review a book that is apparently so important–to compare it to Oedipus Rex and a few Talking Heads songs. And I’ll admit that if Freedom had not been so wildly over-praised in the past few months, I’d probably try to find something positive to say about it. So I’ll try: Franzen is deeply intelligent, even wise, and his analysis of the past decade is perhaps brilliant. It’s also incredibly easy to read, but this is mostly because it requires so little thought from the reader. Franzen has done all the thinking for you. The book has a clear vision, a mission even, but it lacks urgency and immediacy; it is flaccid, flabby, overlong. It moans where it should howl. Nevertheless, the book is not a failure, at least not on its own terms. I believe that Franzen has written the book that he intended to write, that he has documented the zeitgeist the way that he perceives it–I just happen to find his analysis dull and his characters irredeemably uninteresting. Do not feel obligated to read Freedom.

So, Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom is out today. The follow-up to 2001’s The Corrections was already in a second printing before its release today, pretty much pointing to the book being “the literary event” of 2010 (whatever that means). I haven’t read Freedom yet so I don’t have an opinion about it–but it’s hard to not have an opinion about the opinions about Freedom, at least if you follow literary-type news. The

So, Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom is out today. The follow-up to 2001’s The Corrections was already in a second printing before its release today, pretty much pointing to the book being “the literary event” of 2010 (whatever that means). I haven’t read Freedom yet so I don’t have an opinion about it–but it’s hard to not have an opinion about the opinions about Freedom, at least if you follow literary-type news. The

Time

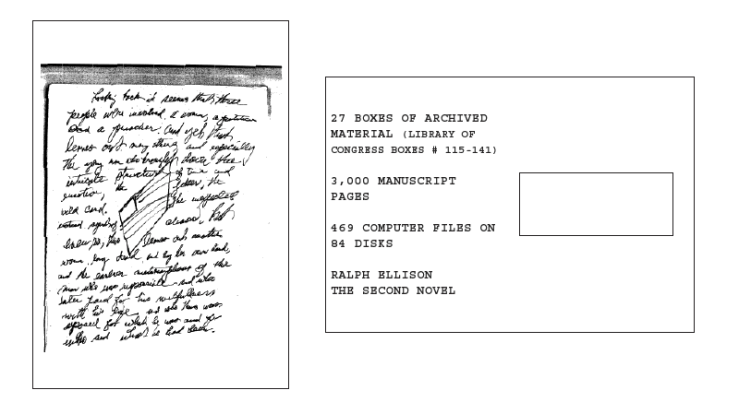

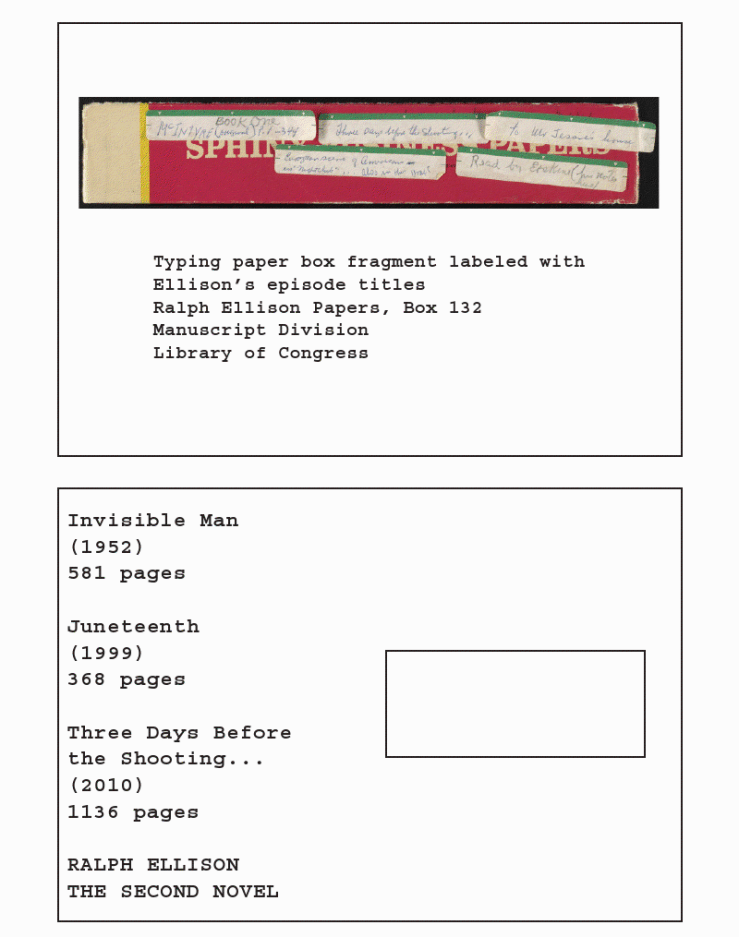

Time  A second novel from Ralph Ellison? Wasn’t that Juneteenth, the posthumous work pieced together from thousands of pages and notes by Ellison’s literary executor, John Callahan? The one that was kinda sorta panned as a mess (or at least an incomplete vision)? A few weeks later, another postcard:

A second novel from Ralph Ellison? Wasn’t that Juneteenth, the posthumous work pieced together from thousands of pages and notes by Ellison’s literary executor, John Callahan? The one that was kinda sorta panned as a mess (or at least an incomplete vision)? A few weeks later, another postcard: So we were still a little confused. Was Three Days Before the Shooting… a more complete version of Juneteenth, or a wholly separate novel? A week or two later, a third postcard showed up with some answers: Ralph Ellison’s Three Days Before the Shooting… is a re-edit of the material originally presented as Juneteenth back in 1999, expanded from 368 pages to 1136 pages. Hopefully, Ellison’s vision will be restored here.

So we were still a little confused. Was Three Days Before the Shooting… a more complete version of Juneteenth, or a wholly separate novel? A week or two later, a third postcard showed up with some answers: Ralph Ellison’s Three Days Before the Shooting… is a re-edit of the material originally presented as Juneteenth back in 1999, expanded from 368 pages to 1136 pages. Hopefully, Ellison’s vision will be restored here.