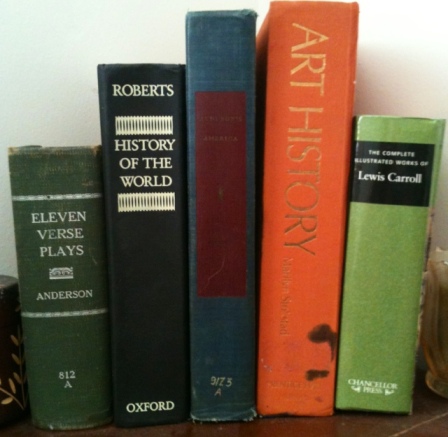

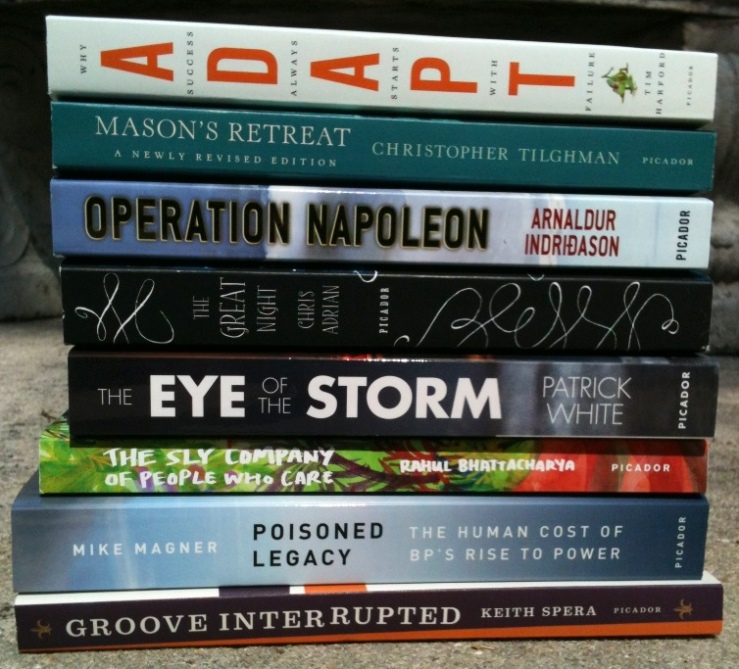

A nice stack from the good folks at Picador this month, including two new entries in their ongoing Nadine Gordimer reissues. I like the design on the series:

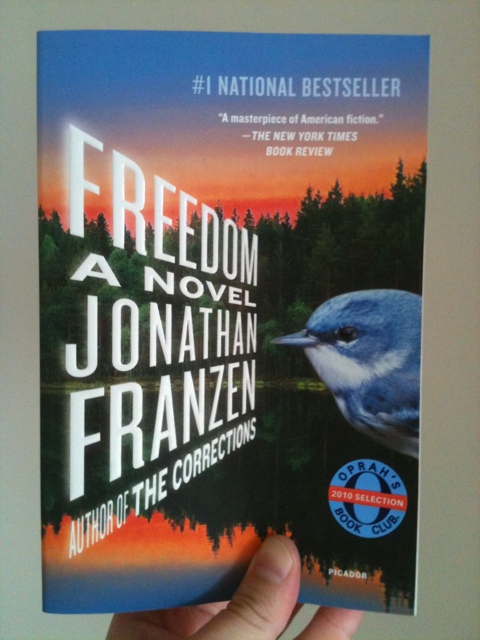

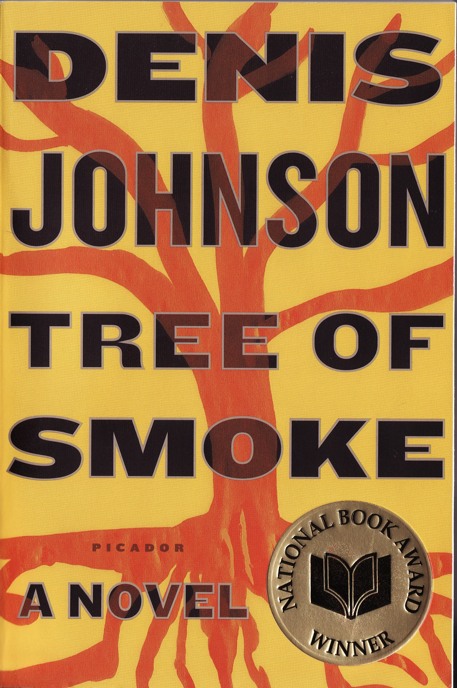

There’s also a reissue of Denis Johnson’s 1991 novel Resuscitation of a Hanged Man, which I haven’t read, but will read soon, because Johnson is just one of those writers I’ll end up reading everything by eventually. From a 1991 NYT review of the novel:

There has never been any doubt about Denis Johnson’s ability to write a gorgeous sentence. The author of “Angels,” “Fiskadoro” and “The Stars at Noon” has become increasingly musical in his prose, and his latest novel, “Resuscitation of a Hanged Man,” depends on such sentences as the primary unit of narrative motion. The novel seems, like a poem, to be written line to line. It is very much a book about one man, one sensibility.

At the outset of the novel, Leonard English, driving to the tip of Cape Cod in the off season, stops for a drink, then spins out of control, running his car onto a traffic island. He ends up taking a taxi to his destination, which is Provincetown. He has attempted suicide before the book’s beginning; now he is moving to the Cape to work for Ray Sands, a private investigator who also owns a small radio station. When we can see him most clearly, English seems very similar to the narrator of the short story — drifting, guilty, in a world of strangers, striving to connect with another person and with his God.

Last year’s With Liberty and Justice for Some is out now in trade paperback. If you are even slightly familiar Glenn Greenwald’s columns at Salon, you’ll likely know what to expect. For those of us predisposed to agree with his analyses, With Liberty and Justice for Some is likely to inspire outrage and a certain kind of fatigue.

Here’s an excerpt from an interview between Harper’s Scott Horton and Greenwald:

American history is suffused with violations of equality before the law. The country was steeped in such violations at its founding. But even when this principle was being violated, its supremacy was also being affirmed: resoundingly and unanimously in the case of the founders. That the rule of law—not the rule of men—would reign supreme was one of the few real points of agreement among all the founders. Arguably it was the primary one.

There’s an obvious element of hypocrisy in this fact; espousing a principle that one simultaneously breaches in action is hypocrisy’s defining attribute. But there’s also a more positive side: the country’s vigorous embrace of the principle of equality before law enshrined it as aspiration. It became the guiding precept for how “progress” was understood, for how the union would be perfected.

And the most significant episodes of progress over the next two centuries—the emancipation of slaves, the ending of Jim Crow, the enfranchisement and liberation of women, vastly improved treatment for Native Americans and gay Americans—were animated by this ideal. That happened because “blind justice”—equality before law—was orthodoxy in American political culture. The principle was sacrosanct even when it was imperfectly applied.

The Ford pardon of Nixon changed that, radically and permanently. When President Ford went on national television to explain to an angry, skeptical citizenry why the most powerful political actor would be fully immunized for the felonies he got caught committing, Ford expressly rejected the rule of law. He paid lip service to its core principle—the “law is no respecter of persons”—but then tacked on a newly concocted amendment designed to gut that principle: “but the law is a respecter of reality.”

In other words, if—in the judgment of political leaders—it’s sufficiently disruptive, divisive, or distracting to hold powerful political officials accountable under the law on equal terms with ordinary Americans, then they should be exempt and the rule of law suspended, all in the name of political harmony, of “moving on.” But of course, it willalways be divisive and distracting, by definition, to prosecute the most powerful political leaders, so Ford’s rationale, predictably, created a template for elite immunity.

The rationale for Ford’s pardon of Nixon was subsequently legitimized, and it created a precedent for shielding the most powerful elites from the consequences of their lawbreaking. The arguments Ford offered are the same ones now hauled out over and over whenever it is time to argue why the most powerful among us should not be held accountable: It’s not just for the good of the immunized criminal, but in the common good, to Look Forward, Not Backward. This direct assault on the rule of law was pioneered by the pardon of Richard Nixon.

Steve Sem-Sandberg’s The Emperor of Lies is a Swedish novel in English Translation by Sarah Death. Look, I’m generally dismissive of Holocaust fiction because 1) the sheer number of books that come in to Biblioklept World Headquarters that use the Holocaust as a milieu and 2) the tacky and generally lazy way that such books often attempt to manipulate their audiences. Still, The Emperor of Lies seems like it’s probably a sight better than most such books, and it’s gotten generally good reviews, including this one from The Independent (UK), which apparently thinks that a book review of five sentences is fine:

Any writer – let alone one from neutral Sweden – who sets out to place another brick in the vast wall of Holocaust fiction must be deluded or inspired. Astonishing to report: Sem-Sandberg belongs in the tiny second band.

Utterly involving, morally scrupulous, written with a verve and pace that belie its dreadful setting, The Emperor of Lies – in Sarah Death’s masterly translation – really does renew the genre.

Its portrait of resistance and survival in the ghetto of Lodz between 1940 and 1944 focuses on the monstrous enigma of Chaim Rumkowski, despotic overlord of his fellow-Jews. Sem-Sandberg catches his capricious charisma. Other characters, who record their fate or fight it, also shine, while their tragic destiny moves on at mesmerising speed.

Nice little stack from the good people at Picador—novels, reissues, first-time-in-trade-paperbacks, nonfiction . . . a nice little spread.

Nice little stack from the good people at Picador—novels, reissues, first-time-in-trade-paperbacks, nonfiction . . . a nice little spread.