. . . it’s not too difficult, very obviously, to keep ten or twenty or let’s say even a hundred books; but once you start to have 361, or a thousand, or three thousand, and especially when the total starts to increase every day or thereabouts, the problem arises, first of all of arranging all these books somewhere and then of being able to lay your hand on them one day when, for whatever reason, you either want or need to read them at last or even to reread them.

Thus the problem of a library is twofold: a problem of space, first of all, then a problem of order.

—Georges Perec, from “Brief Notes on the Art and Manner of Arranging One’s Books” (1978)

Book shelves series #2, second Sunday of 2012. Master bedroom: Corner piece bookshelf in the southwest corner; two tiers + top shelf.

I didn’t take a picture of the entire bookshelf, a humble little two-tier piece that abuts the corner of any room with corners. Actually, I did take a picture—a few—but they just looked awful. Like I said in the first installment of this series, it’s not my goal to present aesthetically pleasing portraits of bookshelves.

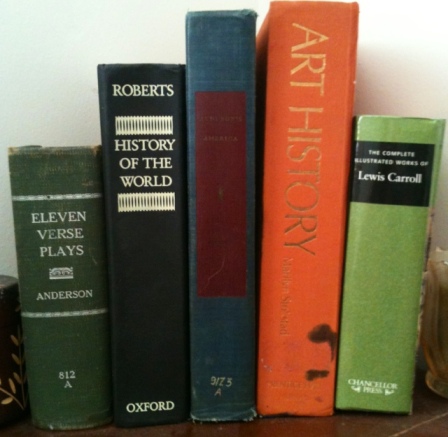

This corner bookshelf was my grandmother’s and I’ve had it for at least 10 years. The top shelf holds five books that rest there for entirely aesthetic purposes; looking at them now I realize that, with the exception of the Audubon volume in the middle and the Lewis Carroll on the end, I’ve never even bothered to flick through them. They look strange photographed here without the framed photographs, plants, and tchotchkes that attend most shelves in the house:

At one point, this entire piece of furniture was double shelved (is this a term? Do you know what I mean here?) with cheap mass market paperbacks, the kind of books that I bought and received for years. I rarely buy mass markets anymore; nor do I like hardbacks. I’m a trade paperback man. Still, some of the sci-fi/dystopian lit here was fundamental to my early reading habits, to the point where I even pick up newer volumes (like Philip Pullman’s books) in mass market paperback.

We also see here the first of many cameras scattered throughout the books in this house. This particular Polaroid is likely the least antiquated; I think it’s from 1999 or 2000. I took all these photos with an iPhone:

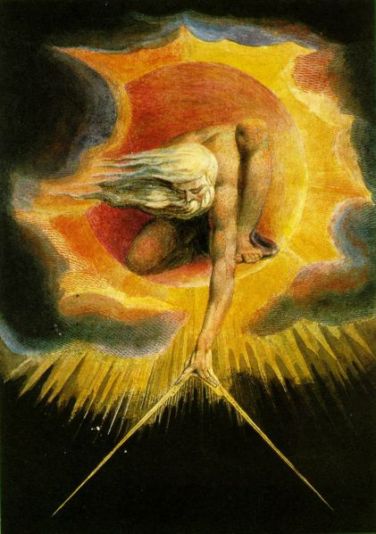

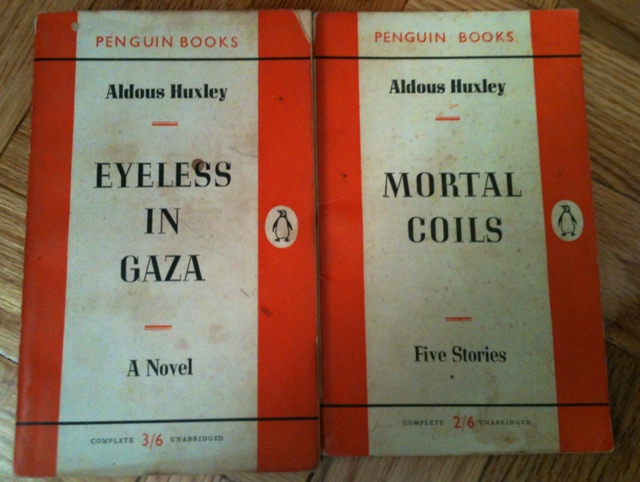

The shot is blurry, so you might not make out the cracked spines, but there are many Huxley books there (although it occurs to me now how odd it is that only one Vonnegut volume is there, when I know that I have so many more somewhere). Two noteworthy Huxleys:

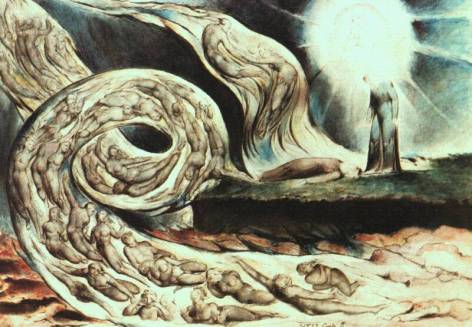

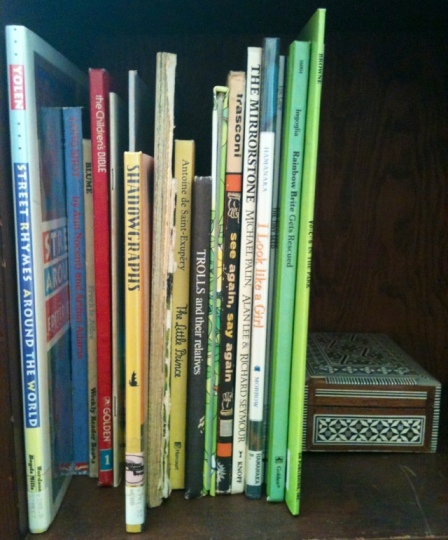

We have children. There are children’s books everywhere in the house, organized in no particular fashion. The drawing and painting books belonged to my grandmother, who was an amateur painter. I am fairly familiar with these books.

More kids books. They were probably stuffed here after piling up on the floor one night. The box is full of homemade dice and preserved insects:

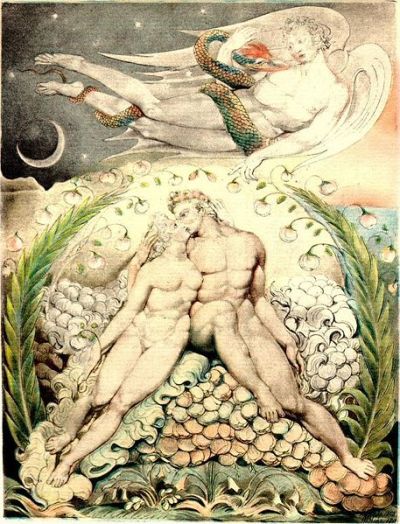

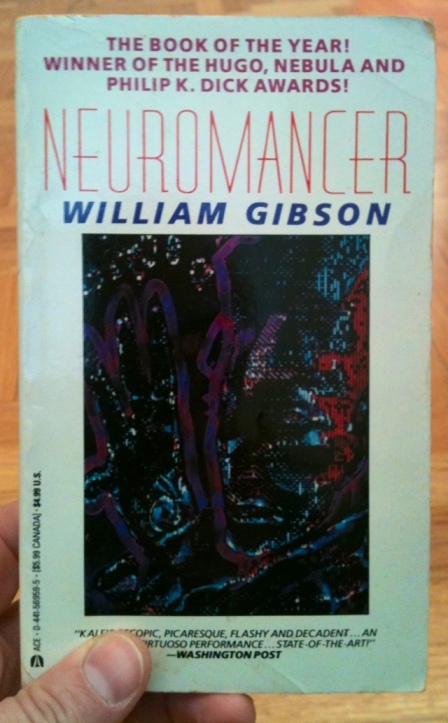

And more mass markets—sci-fi and fantasy. Many of these were, uh, “borrowed” and never returned, either from a school that I used to work for (The Left Hand of Darkness; Alas Babylon, the aforementioned Pullman volumes), or from dear friends (I’m looking at you, William Gibson books). There are probably 50 more books like this in a secret stash in the back of the house, out of sight:

The Lord of the Rings trilogy is an early paperback edition, sporting Tolkien’s original illustrations. My aunt gave me these. I’ve probably read The Lord of the Rings more than any other book, and I’m almost certain that I’ve owned it in more editions than any other book:

A dear friend lent me Gibson’s Neuromancer years ago; I know Gibson’s other early books (the first two trilogies) must be somewhere around the house, unless I passed them on, but I’ve always been fond of this book, which taught me how to read in some ways:

So we’ve made it out of my bedroom—I chose not to take a picture of my wife’s night stand, for her privacy, I suppose, although she might not have cared. (She doesn’t read this blog and is likely unaware of this weird project). There was a Hayao Miyazaki adaptation she was reading to our daughter there, and Hemingway’s novel The Garden of Eden, which I think she finished just the other night.