Job, His Wife, and His Friends, c.1785 by William Blake (1757-1827)

Tag: William Blake

Homer and the Ancient Poets — William Blake

Homer and the Ancient Poets, 1827 by William Blake (1757-1827)

Lear and Cordelia in Prison — William Blake

Lear and Cordelia in Prison, c.1779 by William Blake (1757–1827)

David Delivered out of Many Waters — William Blake

David Delivered out of Many Waters, c. 1805 by William Blake (1757–1827)

Judas Betrays Him — William Blake

Judas Betrays Him, c. 1805 by William Blake (1757–1827)

God Judging Adam — William Blake

God Judging Adam, 1795 by William Blake (1757-1827)

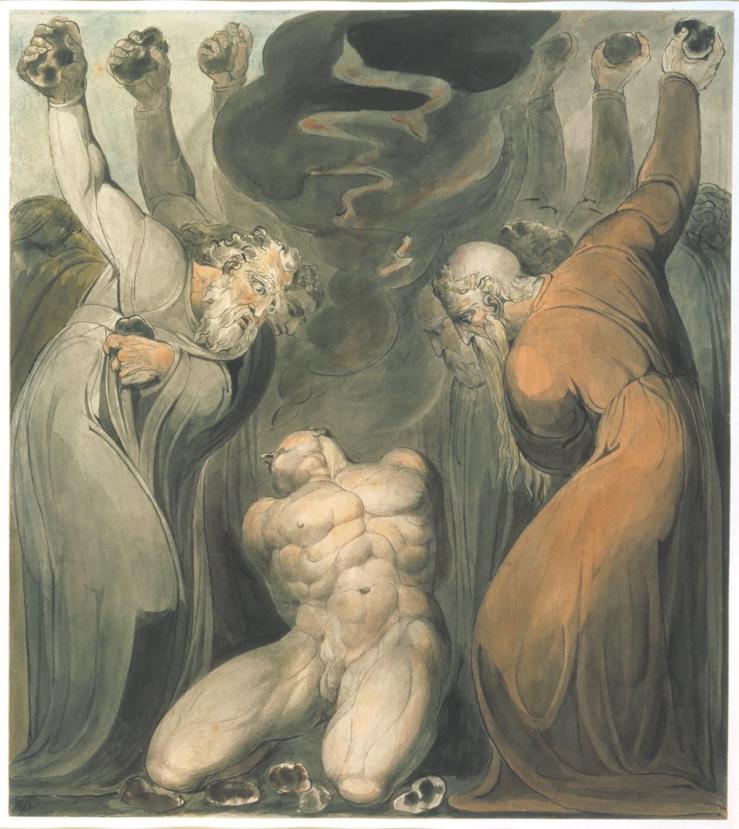

The Blasphemer — William Blake

The Blasphemer, c. 1800 by William Blake (1757-1827)

And he that blasphemeth the name of the LORD, he shall surely be put to death, and all the congregation shall certainly stone him: as well the stranger, as he that is born in the land, when he blasphemeth the name of the LORD, shall be put to death.

—Leviticus 24:16, King James Version

The Wandering Moon — William Blake

The Wandering Moon, 1820 by William Blake (1757-1827)

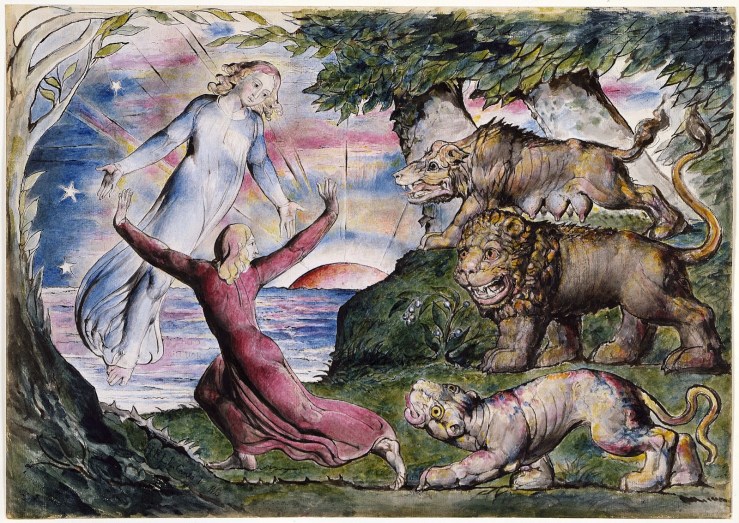

Dante Running from the Three Beasts — William Blake

Dante Running from the Three Beasts, 1827 by William Blake (1757-1827)

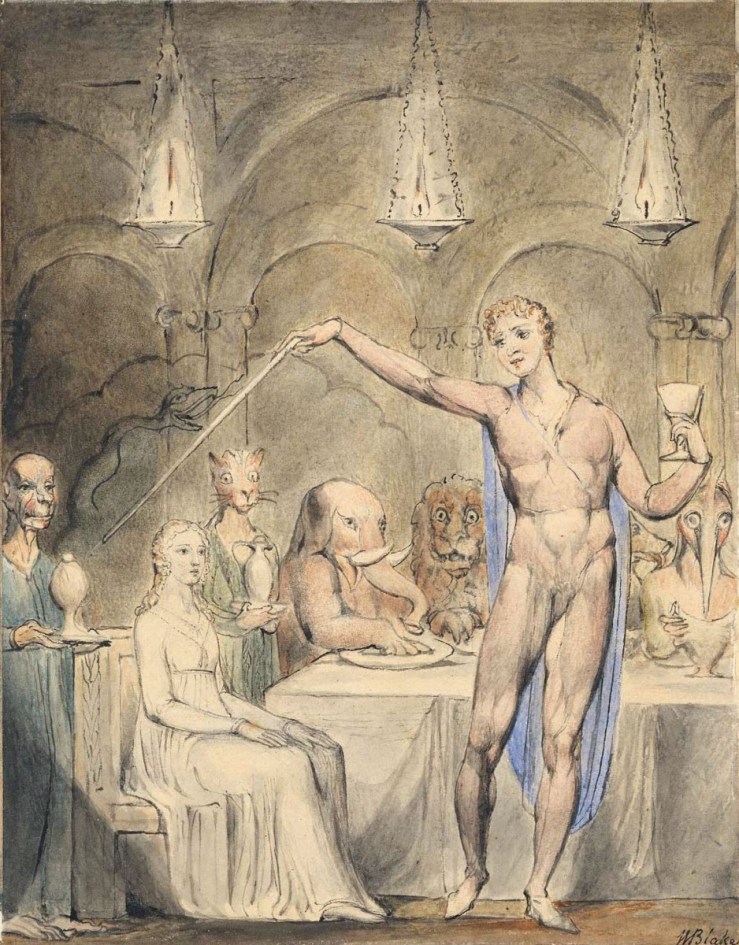

The Magic Banquet — William Blake

Frontispiece for The Song of Los — William Blake

The Song of Los (frontispiece), 1794 by William Blake (1757–1827)

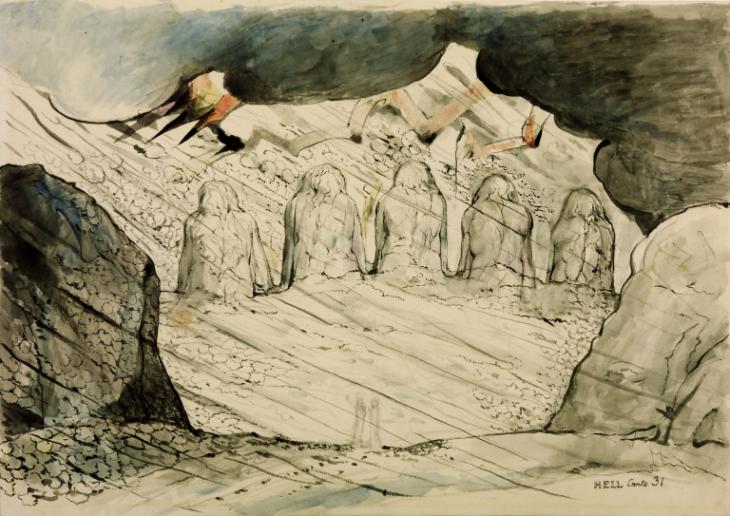

The Primaeval Giants Sunk in the Soil — William Blake

The Primaeval Giants Sunk in the Soil, 1824–27 by William Blake (1757–1827)

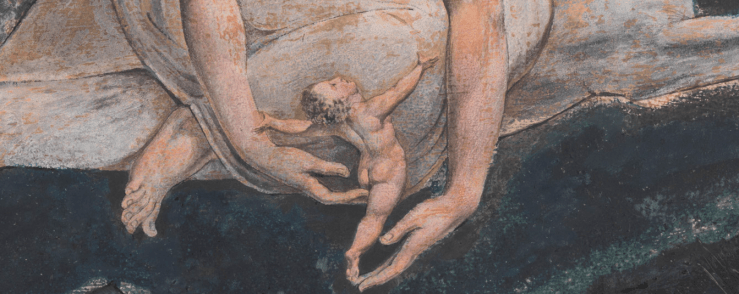

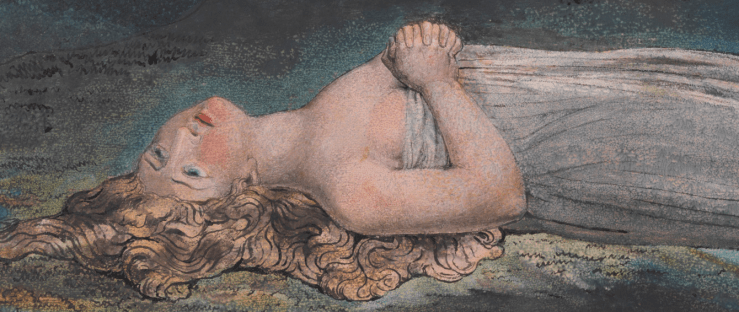

Pity — William Blake

Pity, c. 1795 by William Blake (1757–1827)

The Erstwhile, B. Catling’s sequel to The Vorrh (Book acquired, 17 Feb. 2017)

B. Catling’s sequel to The Vorrh arrived last week, reminding me that I still need to read The Vorrh.

Publisher Vintage’s blurb:

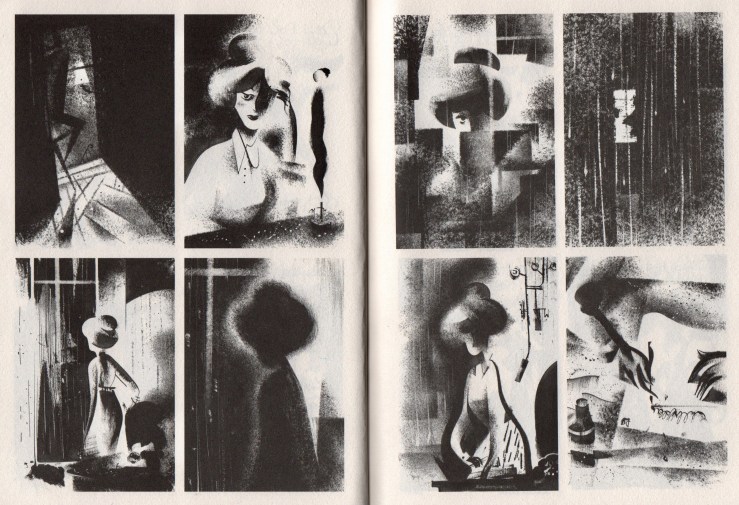

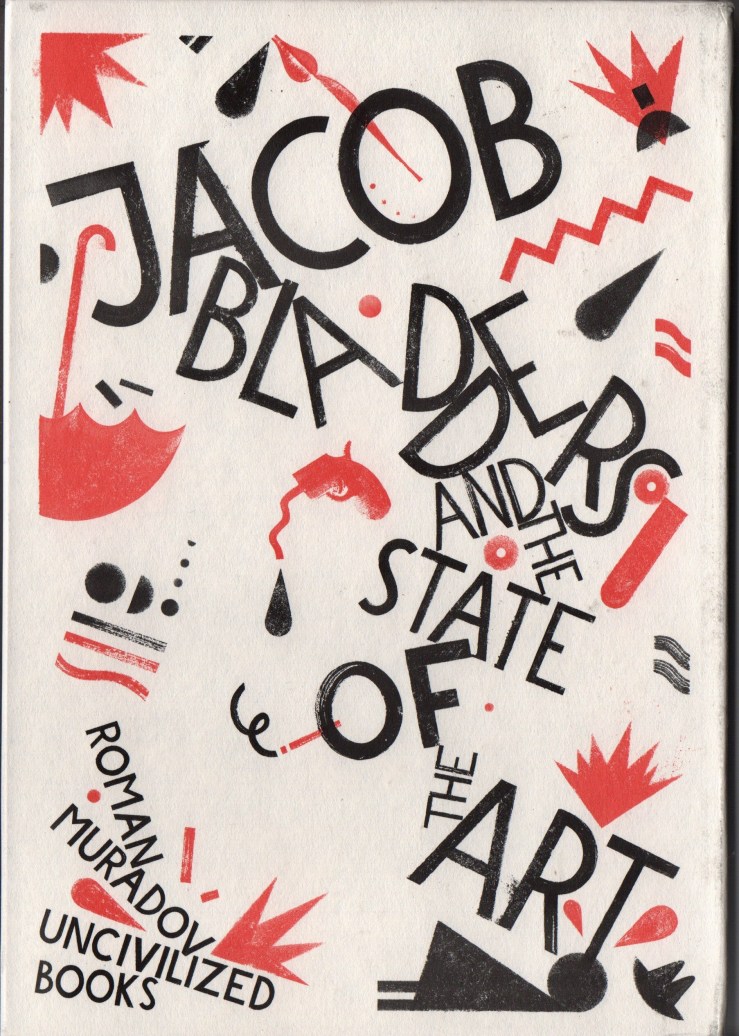

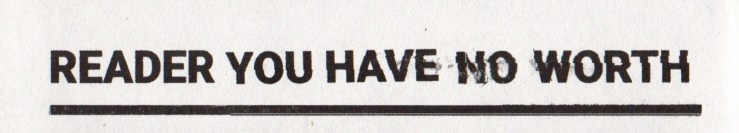

Roman Muradov’s graphic novella Jacob Bladders and the State of the Art reviewed

Roman Muradov’s newest graphic novella, Jacob Bladders and the State of the Art (Uncivilized Books, 2016), is the brief, shadowy, surreal tale of an illustrator who’s robbed of his artwork by a rival.

There’s more of course.

In a sense though, the plot is best summarized in the first line of Jacob Bladders:

Okay.

Maybe that’s too oblique for a summary (or not really a summary at all, if we’re being honest).

But it’s a fucking excellent opening line, right?

Like I said, “There’s more” and if the more—the plot—doesn’t necessarily cohere for you on a first or second reading, don’t worry. You do have worth, reader, and Muradov’s book believes that you’re equipped to tangle with some murky noir and smudgy edges. (It also trusts your sense of irony).

The opening line is part of a bold, newspaperish-looking introduction that pairs with a map. This map offers a concretish anchor to the seemingly-abstractish events of Jacob Bladders.

The map isn’t just a plot anchor though, but also a symbolic anchor, visually echoing William Blake’s Jacob’s Ladder (1805). Blake’s illustration of the story from Genesis 28:10-19 is directly referenced in the “Notes” that append the text of Jacob Bladders. There’s also a (meta)fictional “About the Author” section after the end notes (“Muradov died in October of 1949”), as well as twin character webs printed on the endpapers.

Along with the intro and map, these sections offer a set of metatextual reading rules for Jacob Bladders. The map helps anchor the murky timeline; the character webs help anchor the relationships between Muradov’s figures (lots of doppelgänger here, folks); the end notes help anchor Muradov’s satire.

These framing anchors are ironic though—when Muradov tips his hand, we sense that the reveal is actually another distraction, another displacement, another metaphor. (Sample end note: “METAPHOR: A now defunct rhetorical device relying on substitution of a real-life entity with any animal”).

It’s tempting to read perhaps too much into Jacob Bladder’s metatextual self-reflexivity. Here is writing about writing, art about art: an illustrated story about illustrating stories. And of course it’s impossible not to ferret out pseudoautobiographical morsels from the novella. Roman Muradov is, after all, a working illustrator, beholden to publishers, editors, art-directors, and deadlines. (Again from the end notes: “DEADLINE: A fictional date given to an illustrator to encourage timely delivery of the assignment. Usually set 1-2 days before the real (also known as ‘hard’) deadline”). If you’ve read The New Yorker or The New York Times lately, you’ve likely seen Muradov’s illustrations.

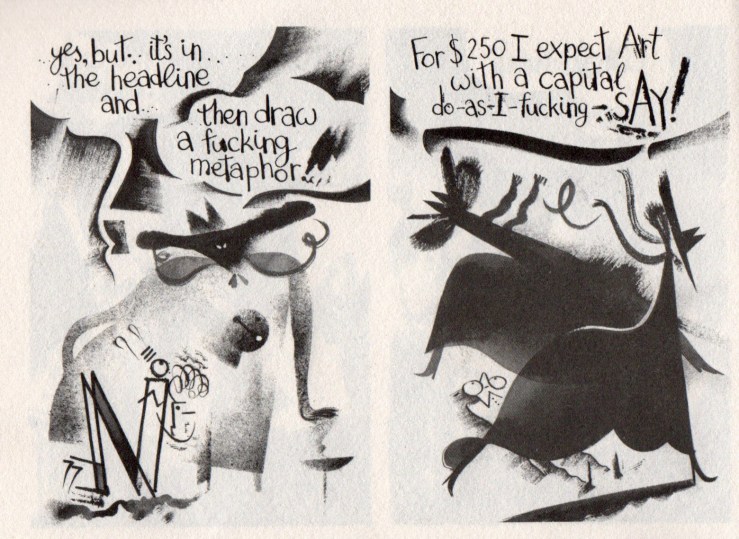

So what to make of the section of Jacob Bladders above? Here, a nefarious publisher commands a hapless illustrator to illustrate a “career ladders” story without using an illustration of a career ladder (From the end notes: “CAREER LADDER: An illustration of a steep ladder, scaled by an accountant in pursuit of a promotion or a raise. The Society of Illustrators currently houses America’s largest collection of career ladders, including works by M.C. Escher, Balthus, and Marcel Duchamp”).

Draw a fucking metaphor indeed. (I love how the illustrator turns into a Cubist cricket here).

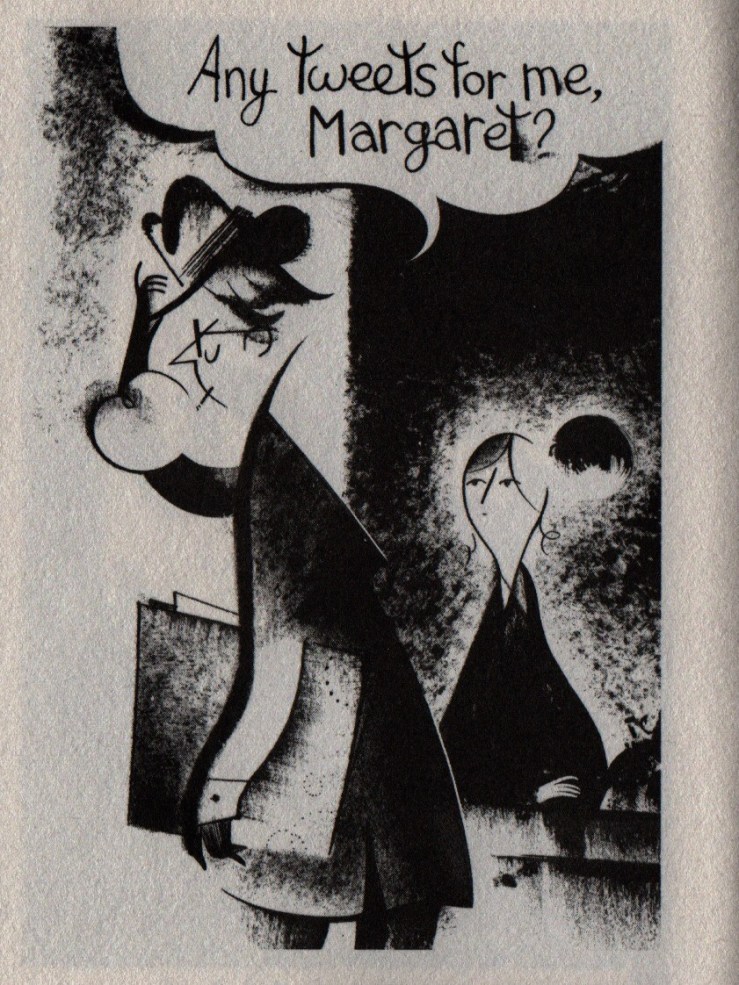

Again, it’s hard not to find semi-autobiographical elements in Jacob Bladders’s publishing satire. Muradov couches these elements in surreal transpositions. The first two panels of the story announce the setting: New York / 1947—but just a few panels later, the novella pulls this move:

Here’s our illustrator-hero Jacob Bladders asking his secretary (secretary!) for “any tweets”; he seems disappointed to have gotten “just a retweet.” In Muradov’s transposition, Twitter becomes “Tweeter,” a “city-wide messaging system, established in 1867” and favored by writers like E.B. White and Dorothy Parker.

Do you follow Muradov on Twitter?

I do. Which makes it, again, kinda hard for me not to root out those autobiographical touches. (He sometimes tweets on the illustration biz, y’see).

But I’m dwelling too much on these biographical elements I fear, simply because, it’s much, much harder to write compellingly about the art of it all, of how Muradov communicates his metatextual pseudoautobiographical story. (Did I get enough postmoderny adjectives in there? Did I mention that I think this novella exemplary of post-postmodernism? No? These descriptions don’t matter. Look, the book is fucking good).

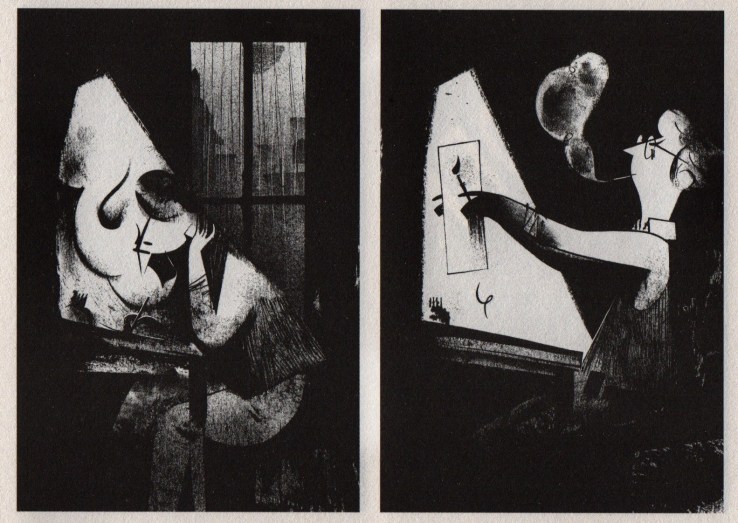

Muradov’s art is better appreciated by, like, looking at it instead of trying to describe it (this is an obvious thing to write). Look at this spread (click on it for biggeration):

The contours, the edges, the borders. The blacks, the whites, the notes in between. This eight-panel sequence gives us insides and outsides, borders and content, expression and impression. Watching, paranoia, a framed consciousness.

And yet our reading rules—again, from the end notes: “SPOTILLO: Spot illustration. Most commonly a borderless ink drawing set against white background”; followed by “CONSTRAINT: An arbitrary restriction imposed on a work of art in order to give it an illusion of depth”.

Arbitrary? Maybe. No. Who cares? Look at the command of form and content here, the mix and contrast and contradistinctions of styles: Cubism, expressionism, impressionism, abstraction: Klee, Miro, Balthus, Schjerfbeck: Robert Wiene and Fritz Lang. Etc. (Chiaroscuro is a word I should use somewhere in this review).

But also cartooning, also comix here—Muradov’s jutting anarchic tangles, often recoiling from the panel proper, recall George Herriman’s seminal anarcho-strip Krazy Kat. (Whether or not Muradov intends such allusions is not the point at all. Rather, what we see here is a continuity of the form’s best energies). Like Herriman’s strip, Muradov’s tale moves under the power of its own dream logic (more of a glide here than Herriman’s manic skipping).

That dream logic follows the lead (lede?!) of that famous Romantic printmaker and illustrator William Blake, whose name is the last “spoken” word of the narrative (although not the last line in this illustrated text). Blake is the illustrator of visions and dreams—visions of Jacob’s Ladder, Jacob Bladders. Jacob Bladders and the State of the Art culminates in the Romantic/ironic apotheosis of its hero. The final panels are simultaneously bleak and rich, sad and funny, expressive and impressive. Muradov ironizes the creative process, but he also points to it as an imaginative renewal. “Imagination is the real,” William Blake advised us, and Muradov, whether he’d admit it or not, makes imagination real here. Highly recommended.

A place must be made for innocence | Gravity’s Rainbow, annotations and illustrations for page 419

In a corporate State 1, a place must be made for innocence, and its many uses 2. In developing an official version of innocence, the culture of childhood has proven invaluable 3 . Games, fairy-tales, legends from history, all the paraphernalia of make-believe 4 can be adapted and even embodied in a physical place, such as at Zwölfkinder 5. Over the years it had become a children’s resort, almost a spa. If you were an adult, you couldn’t get inside the city limits without a child escort. There was a child mayor 6, a child city council of twelve. Children picked up the papers, fruit peelings and bottles you left in the street, children gave you guided tours through the Tierpark 7, the Hoard of the Nibelungen 8, cautioning you to silence during the impressive re-enactment of Bismarck’s elevation, at the spring equinox of 1871, to prince and imperial chancellor 9,… child police reprimanded you if you were caught alone, without your child accompanying. Whoever carried on the real business of the town—it could not have been children—they were well hidden.10

From page 419 of Thomas Pynchon’s 1973 novel Gravity’s Rainbow.

1 Pynchon, as always, diagnoses not just the past and present, but the future. The state is corporate; They — the oligarchy et al. — run the show. And conceptualizing innocence is part of running that show.

2 Cf. William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and Experience (1789). In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793), Blake wrote: “Without Contraries is no progression.” Without corruption there is no innocence; without abjection there is no purity; without an elect, there is no preterite.

Blake’s Songs share much in common with Pynchon’s big novel—both argue for the preterite, pointing out the ways in which industrial technologies exploit the most vulnerable among us; both are wildly, acidly vivid; both employ metaphors of fall and ascent; both foreground the utterly real humanity of their subjects.

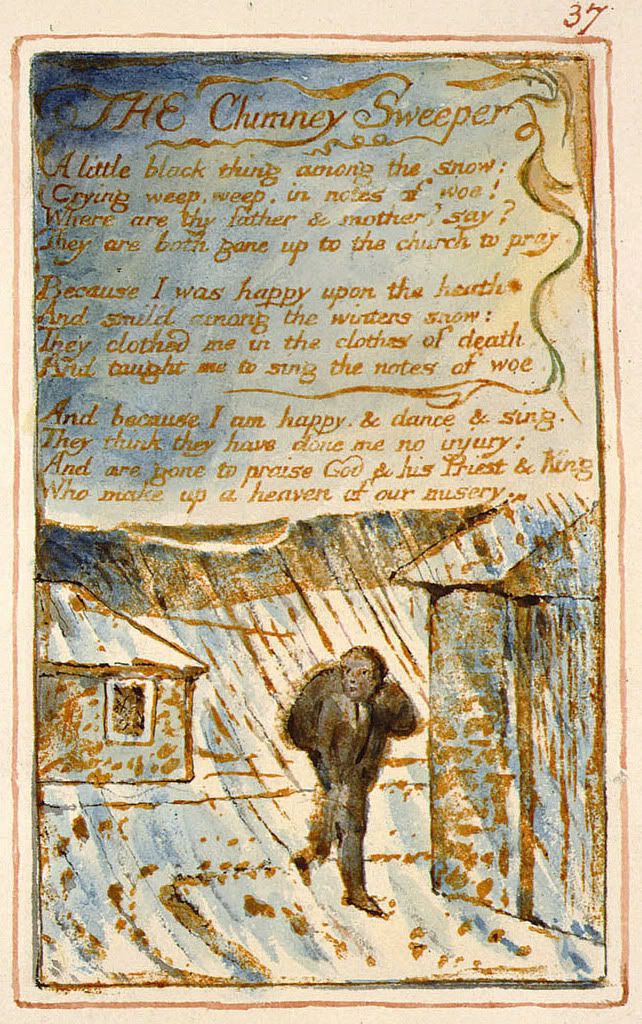

Blake’s “The Chimney Sweeper” (from Experience) shows in simple language how the official version of innocence can be used to enforce the dominant and exploitative order. Consider the last stanza:

And because I am happy and dance and sing,They think they have done me no injury,And are gone to praise God and his Priest and King,Who make up a heaven of our misery

Blake’s chimney sweeper asserts his right to happiness, to laughter and joy. The creative impulse is a Counterforce against Them—here, the Priest and King. Yet They co-opt the dancing and joy and convert it into signs of “the official version of innocence”: a lie to cover over the utter corruption of the dominant order.

3 You’ve read Freud, right? Like, those ideas on infantile sexuality that are downright icky, and yet nevertheless reaffirmed and reinforced by the Corporate State? (Oligarchial capitalism simultaneously infantilizes and sexualizes its subjects). Gravity’s Rainbow does a lot of stuff it’s easier (less queasier) to write off as abject than to actually like, think through. But GR also shows that They infantilize and sexualize childhood in the service of control, as a way of establishing (and blurring and “defiling”) official versions of innocence.

Consider Our Poor Hero Tyrone Slothrop, whose conditioning as an infant by Laszlo Jamf (involving the mysterious MacGuffin Imipolex G) leads to erections that predict rocket strikes. (I swear that sentence makes sense).

4 “Games, fairy-tales, legends from history, all the paraphernalia of make-believe can be adapted and even embodied in a physical places” — physical places like Gravity’s Rainbow. Well, okay. I mean, we get a condensation here of Pynchon’s process, his synthesis, his grab-bag of songs and japes and jibes and jokes and tales and etcetera.

But Pynchon’s pointing out other, perhaps more nefarious and venal and corporate uses for the same cultural material he’s massaging: A fucking theme park. Like, uh, Disneyland. Or Disneyworld. Etcetera, you get it—that we—did I just write We?!—I want to say They—that They colonize and corporatize the imagination; that They gobble up the cultural material and excrete it in smooth, digestible, sanitized (yet subtly sexualized)—and consumable, marketable!—segments that we take our kids to queue up to experience in their innocence.

5 As always, Pynchon Wiki does it better than I can:

“Twelve Children” – the name evokes Jacob’s twelve sons (and the daughter who is not one of the official twelve). This pattern is self-consciously repeated in the Grimms’ tale “The Twelve Brothers”, where the boys are to die if their mother gives birth to a girl.

The camp, which is also a quasi-town, may be modelled after Theresienstadt, the Jewish town/Lager set up by the Nazis in what is now the Czech Republic. This is suggested by themes like transit, phoney children’s paradise, as well as the large orchestra, or the number 60,000 (the number of those who “passed through” Zwölfkinder as well the population of Theresienstadt at its peak). It also recalls another totalitarian institution, that of the communist “children’s towns” (large, town-like, somewhat militarized holiday camps for Young Pioneers), whose prototype was Artek in the Soviet Union. (Deutsches Jungvolk also had its summer camps.)

Further, consider Argentina’s Republic of Children, a city proportioned for children, which was created under Juan Peron’s regime and opened in 1951.

The Oedipal plot of Grimms’ “The Twelve Children” repeats throughout Gravity’s Rainbow, and I invite you to look for it lurking in Disney.

6 Cf. Gravity’s Rainbow page 534—Osbie Feel’s screenplay Doper’s Greed!:

“At the entrance to the town, barring their way, stands the Midget who played the lead in Freaks. The one with the German accent. He is the town sheriff. He is wearing an enormous gold star that nearly covers his chest.”

The little person referenced is Harry Earles who played Hans in Freaks (1932; dir. Tod Browning).

7 The zoo.

8 A vast treasure hoard, such as Scrooge McDuck might dive into, or Bilbo Baggins and his pals might play upon.

The Nibelungen Hoard, as I’m sure you know, is the treasure of the Nibelungen. (You know Wagner’s Ring Cycle, eh? Or you’ve read Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, right?—you get the idea. The titular Nibelung is the dwarf Alberich, by the way).

Cf. W.N. Lettsom—

The tale of that same treasure might well your wonder raise;

’T was much as twelve huge wagons in four whole nights and days

Could carry from the mountain down to the salt-sea bay,

If to and fro each wagon thrice journeyed every day.It was made up of nothing but precious stones and gold;

Were all the world bought from it, and down the value told,

Not a mark the less thereafter were left, than erst was scored.

Good reason sure had Hagan to covet such a hoard.

In the Nibelungenlied, Hagen murders the hero Siegfried and then steals and hides the Nibelung hoard.

9 Otto von Bismarck, 1815-1898, who unified Germany through technocracy and, uh, war.

10 “…they were well hidden”: A précis of Pynchonian paranoia, perhaps.