In his essay “In the Ruins of the Future,” published in December of 2001, Don DeLillo wrote this about the 9/11 attacks: “The writer wants to understand what this day has done to us. Is it too soon?” His question was both profound and at the same time utterly banal—of course it was too soon to measure the effects of the 9/11 attacks. But could time’s distance somehow sharpen or enrich perspective? DeLillo continues: “We seem pressed for time, all of us. Time is scarcer now. There is a sense of compression, plans made hurriedly, time forced and distorted.”

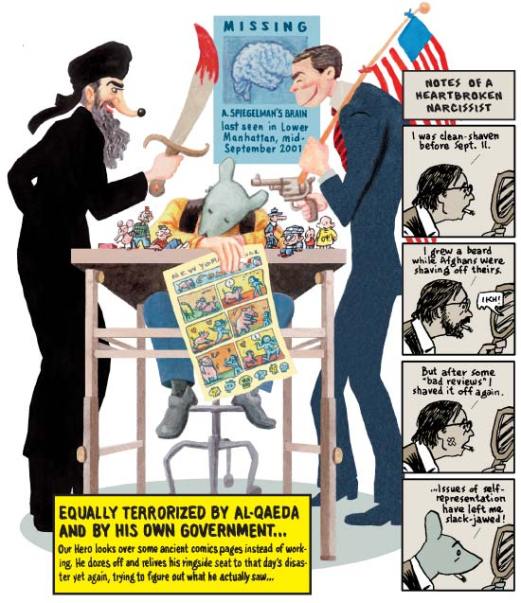

In retrospect—what with the Bush administration’s ludicrous invasion of Iraq and the power-grab of the Patriot Act—DeLillo’s notation of “plans made hurriedly” seems downright scary. Still, I remember that immediate, overwhelming shock, that paralyzing inertia that had to be overcome. DeLillo wanted—needed—to grapple with this spectacular destruction immediately. David Foster Wallace responded with similar immediacy; the caveat that prefaces his moving essay “The View from Mrs. Thompson’s“ states that the piece was “Written very fast and in what probably qualifies as shock.” The same caveat would also apply neatly to Art Spiegelman’s big, brilliant, messy attempt at cataloging his impressions immediately post-9/11, In the Shadow of No Towers.

In contrast, the trio of 9/11 stories at the heart of Chris Adrian’s short story collection, A Better Angel, all employ distance and distortion—both temporal and spatial—as a means to address the disaster (or inability to address the disaster) of the attacks on the World Trade Center. Adrian’s 9/11 tales (and his works in general, really), ask how one can grieve or attest to death on such a massive, spectacular scale. The victims of the 9/11 attacks forever haunt his protagonists, literally possessing them, demons that can’t let go, forcing the living to wallow in grief. In “The Changeling,” for example, the grief of the attacks is literally measured in blood, as a father repeatedly maims himself as the only means to assuage the terror and confusion of his possessed son. Adrian sets one of the collection’s most intriguing tales, “The Vision of Peter Damien,” in nineteenth-century rural Ohio. This temporal distortion veers into metaphysical territory as the titular Damien, along with other children in his village, become sick, haunted by the victims of 9/11. Adrian’s displaced milieu creates a bizarre cognitive dissonance for his readers, a response that DeLillo also articulated in his 2007 novel Falling Man.

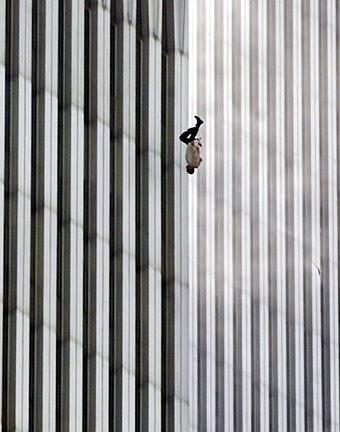

DeLillo initiates the novel as a sort of creation story: “It was not a street anymore but a world, a time and space of falling ash and near night.” The demarcation of this new world recapitulates DeLillo’s initial concern with time and space, but his novel seems ultimately to suggest an inertia, a meaninglessness, or at least the hollow ambiguity of any artistic response. This stands, of course, in sharp contrast to his sense of urgency in his earlier essay. Like the performance artist in the novel who is repeatedly sighted hanging suspended from a harness, there’s a sad anonymity in the background of Falling Man: the artist hangs as static witness to disaster, but looking for comfort, or even perhaps meaning, in the gesture is impossible.

David Foster Wallace’s short story “The Suffering Channel,” (from his 2004 collection Oblivion) is in many ways a far more satisfying take on 9/11, although to be fair, the majority of the story’s events take place in July of 2001. The story (or novella, really; it’s 90 pages) centers around a magazine headquartered in the World Trade Center that plans to run an article—on September 10th, 2001—about a man who literally shits out pieces of art. Wallace’s critique of American culture (shit as art, commerce as style, advertising as language) is devastating against the context of the looming disaster to which his characters are so oblivious. As the novella reaches its close (culminating in the shit artist producing an original work for a live audience), we learn more about “The Suffering Channel,” a cable channel devoted to broadcasting only images of human beings suffering intense and horrible pain. Wallace seems to suggest that The Suffering Channel’s audience watches out of Schadenfreude or morbid fascination, that modern American culture so disconnects people that genuine suffering cannot be witnessed with empathy, but only as a form of spectacular, disengaged entertainment. And yet even as Wallace critiques American culture, the specter of the 9/11 attacks ironically inform his story. With our awful knowledge of what will happen the day after the shit artist article is published, we are able to see the ridiculous and ephemeral nature of the characters’ various concerns. At the same time, Wallace’s tale reveals that empathy for suffering is possible, but also that it comes at a tremendous price.

To contrast the journalistic immediacy of pieces like “In the Ruins of the Future” and “The View from Mrs. Thompson’s” with their respective writers attempts to measure 9/11 in literary fiction is perhaps a bit unfair. Still, Wallace’s and DeLillo’s essays transmit something of the ineffable, visceral quality of that terrible day, as well as the strange ways we sought comfort through human connection. In contrast, the distance and distortion of their literary efforts lose something. I apologize—I don’t have a word for this “something” that the essays have that the novel and novella lack (perhaps the absence is purposeful; perhaps not). It’s not clarity, but perhaps it’s a clarity of distortion that the essays convey, the duress, or to return to Wallace’s own notation, the pieces were “Written very fast and in what probably qualifies as shock.” It’s that shock, I suppose, that I’m trying to name, to say that it’s still there, accessible in those early responses (I realize now I’ve unfairly neglected Spiegelman’s book, which is a great example of immediacy). And to relive that shock is important, because, as Wallace reveals in both of his pieces, the cathartic power of shared tragedy makes us human, allows us to really live, and to be thankful that we do live.

Looking over this piece, I realize that it’s overly long and really says nothing, or at least nothing much about 9/11, or literature, or whatever. But I don’t want to be negative. I highly encourage you to read (or re-read) “The View from Mrs. Thompson’s” and “In the Ruins of the Future.” And I’ll leave it at that.

[Editorial note: We ran a (somewhat sloppier) version of this essay on 9.11.2009]