Just what, exactly, is David Shields’s Reality Hunger supposed to be about? He’s brazen enough to slap the subtitle “A Manifesto” right there under the title, suggesting a work of sustained principles calling for something to change or happen for some reason, but after reading the damn thing, I still have no real idea what he really wants or why I should care. If I had to venture a guess, it seems that Shields is suggesting that we quit reading, writing, and publishing “standard novels” and that “realism” in letters can only be located in lyric essays and other works free from genre constraint (even the memoir is too artificial for Shields, and autobiography ultimately represents facts without truth).

I think what he really wants is authenticity, which repeatedly gets called “reality,” a term he (repeatedly) fails to satisfactorily define. Reality Hunger seems to argue that authenticity in the 21st century must take the form of synthesis, must chop up and recombine disparate elements, genres, cultural artifacts. To that end, Shields’s book is a tour-de-force of citation and appropriation. Aspiring toward an aphoristic tone, Shields organizes the book into 618 short sections over 200 or so pages; most of the sections are not his work, but come rather from myriad sources across different cultures and eras. I have no problem with this (c’mon, this is Biblioklept!) and Shields clearly demonstrates that the practice is hardly new in the history of story-telling, rhetoric, or philosophy.

My real problem is the self-seriousness of it all. Shields aspires to “break” reality into his text by reapportioning and recombining varied citations, but this bid for authenticity is, of course, utterly artificial, often stolid, and not nearly as fun as such a playful medium would suggest. Even worse, it’s not really a proper synthesis; that is, in stacking bits of other people’s work together with some of his own thin connective tissue, Shields hasn’t achieved an authentic blend or, to use a term he’d hate, anything novel, anything new. The jarring stylistic shifts between sections will lead serious readers repeatedly to the book’s appendix to find out who originated the words Shields is copping.

If Reality Hunger approaches having a point, it comes in the book’s penultimate chapter, “Manifesto.” Here, he attacks “standard novels.” The term is appropriated from W.G. Sebald, a writer of marvelous and strange novels that Shields would love to be essays. In one of the few original lines in the book, Shields dismissively writes that “Novel qua novel is a form of nostalgia.” He goes on to argue that the personal/lyric essay is more closely aligned with philosophy, history, and science than novels, and that novels no longer have any legitimate response to these more “real” concerns. Which is utter bullshit, really, and seems more than anything to prove that Shields is probably not that well-read, despite his massive cut and paste catalog. Not that I think that he’s not that well-read. He just picks and chooses, according to his taste, what novels get to escape being “standard.” How can one read contemporary masterpieces like The Rings of Saturn or Infinite Jest or 2666 or Underworld and honestly say that they don’t hold value? Shields, of course, does/would presumably find room for these in his “manifesto.”

The most embarrassing chapter of Reality Hunger, “Hip-hop,” also reveals the most about Shields’s program. It’s also one of the few chapters to feature long sections of Shields’s own original prose. In a turgid, humorless, overly-analytical “defense” of hip-hop and “sampling culture,” Shields describes how hip-hop works, riffing on the function of “realness” in hip-hop, and grasping at the larger implications of a normalized recombinant art form within modern culture. And though I agree with pretty much everything that Shields has to say about piracy and copyright laws, the drastic artificiality of his style and tone is really too much here. It’s like someone trying to explain why a joke is funny.

The worst though is Shields’s assertion that “Our culture is obsessed with real events because we experience hardly any.” The sentence itself is a clever bit of sophistry that falls apart under any real scrutiny. I can name a dozen “real events” that I experienced in the last few hours alone, including eating dinner with my family, talking with my wife, and putting my daughter to bed. Complaining that we are denied “real events,” like the mopes Shields cites from Douglas Coupland’s Generation X who lament their “McLives,” is a way of excusing ourselves from the intensity of being present–at all times–in our own lives. The vapid philosophy of the spoiled whiners in Reality Bites wasn’t attractive back in the early nineties and it’s downright repellent now.

So what does it all add up to? I think that Reality Hunger works well as a description of post-postmodernity. And as much as I’ve ranted against it here it’s actually quite enjoyable as a compendium of clever quotations. As a manifesto though, it’s an utter failure. To be fair, he had no shot of convincing me that the novel is or should be dead. There’s just too much evidence to the contrary.

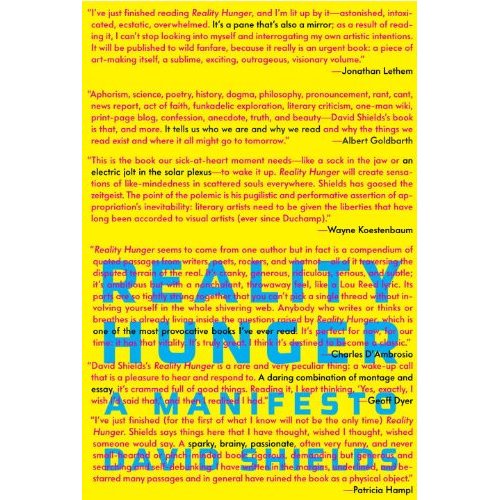

Reality Hunger is now available in hardback from Knopf.