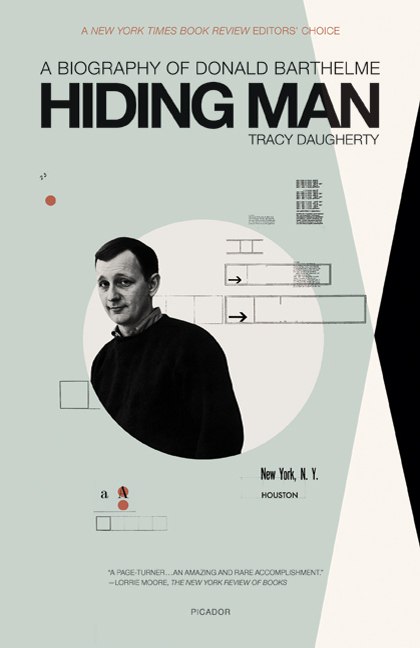

Hiding Man, Tracy Daugherty’s excellent and insightful biography of Donald Barthelme begins with a fascinating anecdote. Daugherty, a student of Bartheleme’s, is told to “Find a copy of John Ashbery’s Three Poems, read it, buy a bottle of wine, go home, sit in front of the typewriter, drink the wine, don’t sleep, and produce, by dawn, twelve pages of Ashbery imitation.” We’re not sure if that sounds like fun homework or not, but it does signal both Barthelme’s imaginative trajectory as well as Daugherty’s intimacy with his subject. Elsewhere in his introduction, he notes that “it’s wrong to think of Don as a victim of neglect. He was, rather, a connoisseur of it.” In short, Daugherty argues that Barthelme was a “Hiding Man,” an artist of structured subtlety who remains under-appreciated and misunderstood.

Daugherty’s book is at once a well-researched biography, a work of cultural and literary criticism, and a writerly affair–that is, its written with a novelist’s fine ear. He weaves Barthelme’s personal life with the man’s stories against the backdrop of a rapidly changing society, weighing Barthelme’s themes and methods along with a shift in literature, art, film, and culture. The book is most interesting when Daugherty situates Barthelme’s writing along/against other writers, particularly the other authors at the forefront of the so-called post-modernist movement. In one late episode, Barthelme organized what has come to be known as “The Postmodern Dinner,” inviting literary giants like William Gaddis, William Gass, John Barth, Kurt Vonnegut, Robert Coover, and Susan Sontag to a fancy SoHo restaurant (Thomas Pynchon politely declined the invite). By 1983, postmodernism had fallen out of favor in lieu of minimalism; Barthelme wasn’t the only writer at the dinner who we might–even now–see as a “victim of neglect.” Many of these writers were attacked (and continue to be attacked) as verbal tricksters, hacks playing at a literary shell game. But, as Daugherty makes very clear in Hiding Man, Barthelme was deeply concerned with matters of meaning and art and philosophy and life and love. He was, like most postmodernists (and Modernists, and post-postmodernists), simply willing to remove some of the strictures that bound distinctions of high and low culture, all as a means of getting closer to a core of truth and perception–not as a means of displacing or denying it. He was an artist.

Hiding Man both begins and ends with an assignment. Daugherty invites Barthelme to read at Oregon State University in early 1989, six months before his death. After the reading, in a moment of utter poignancy, Barthelme asks his former pupil, “Did I do okay for you?” As Barthelme gets in a taxi to leave he gives Daugherty one final assignment: “Write a story about a genius.” Daugherty gets more than a passing grade on this one. Recommended.

Hiding Man is new this month in trade paperback from Picador.