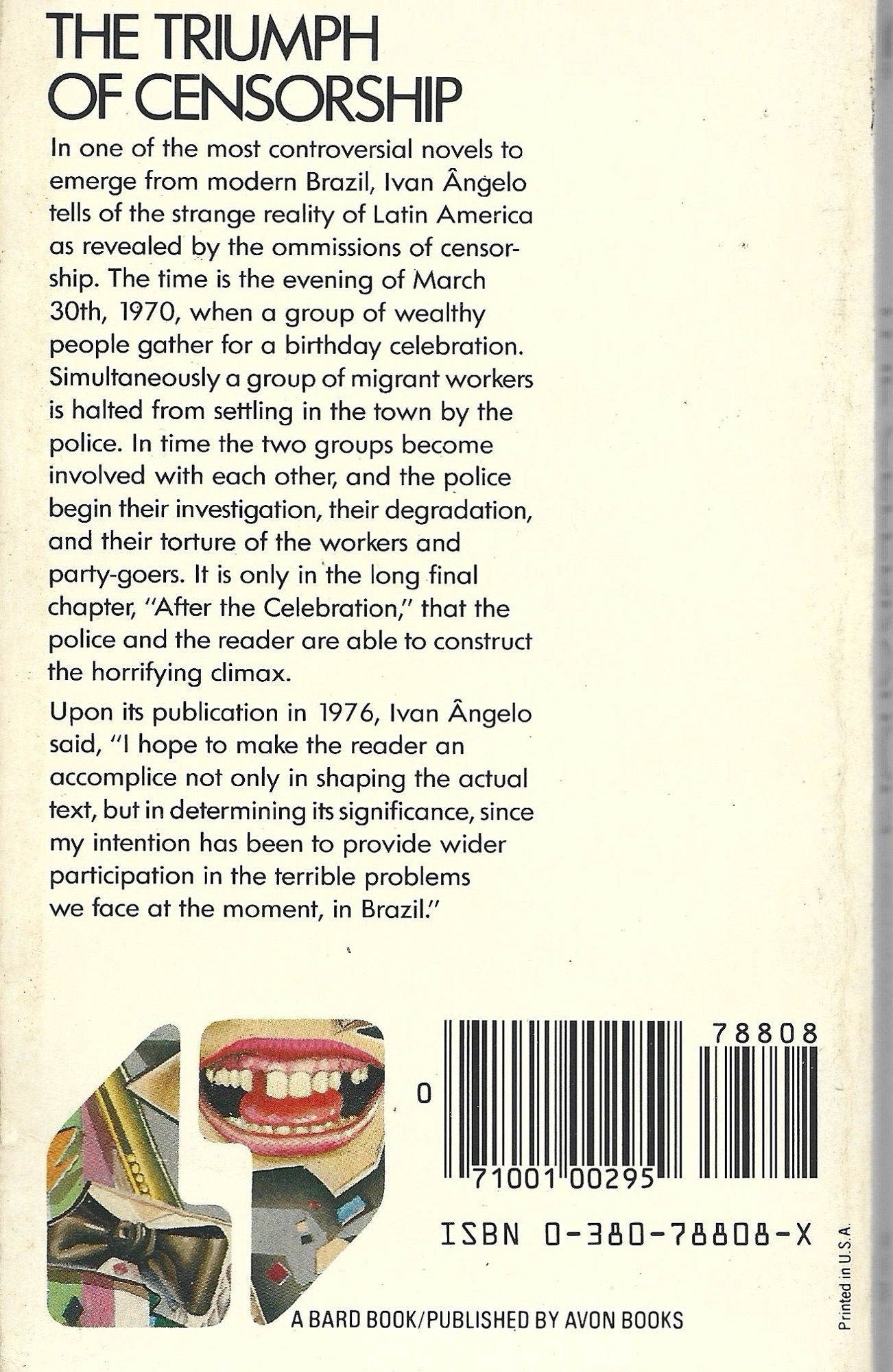

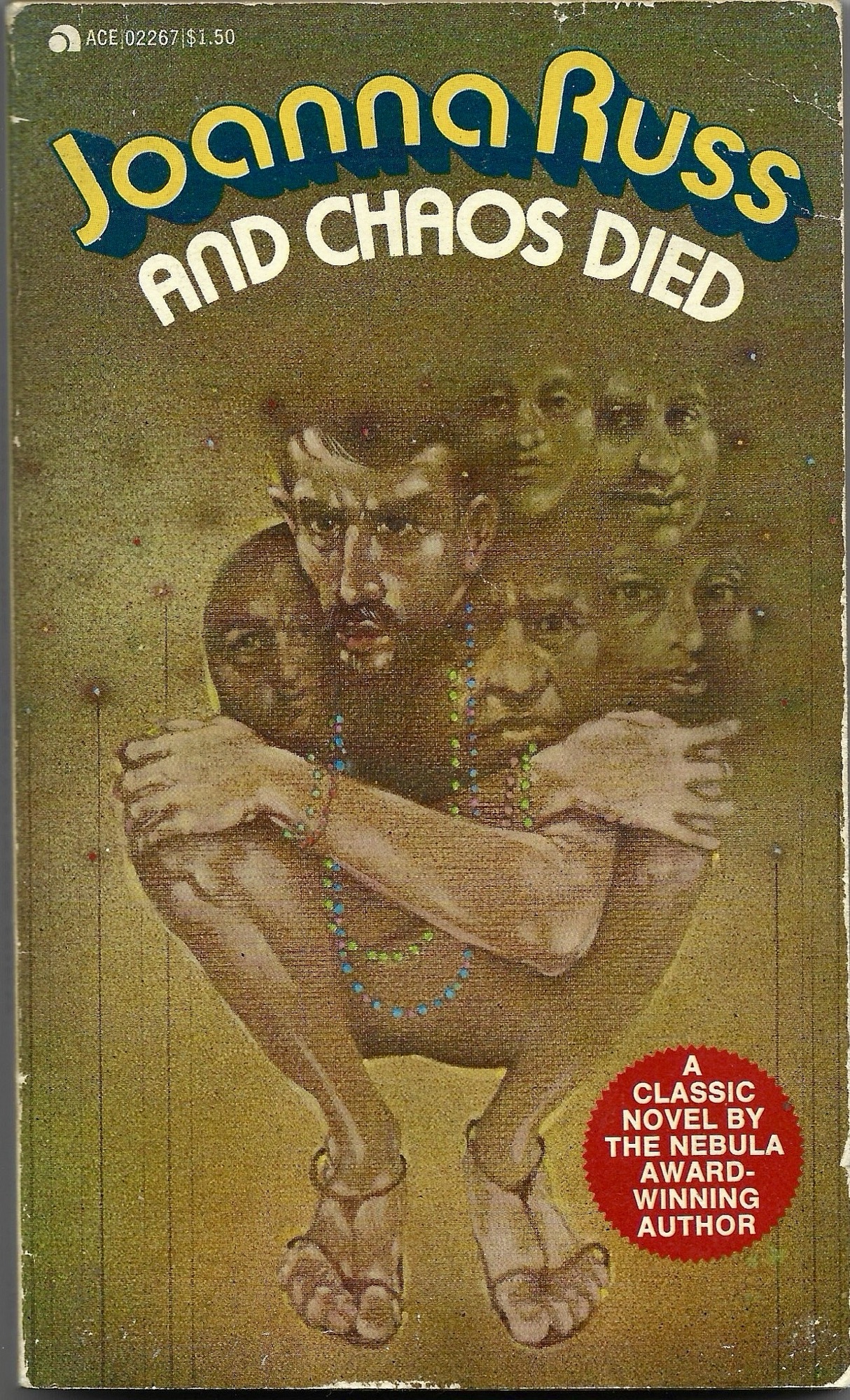

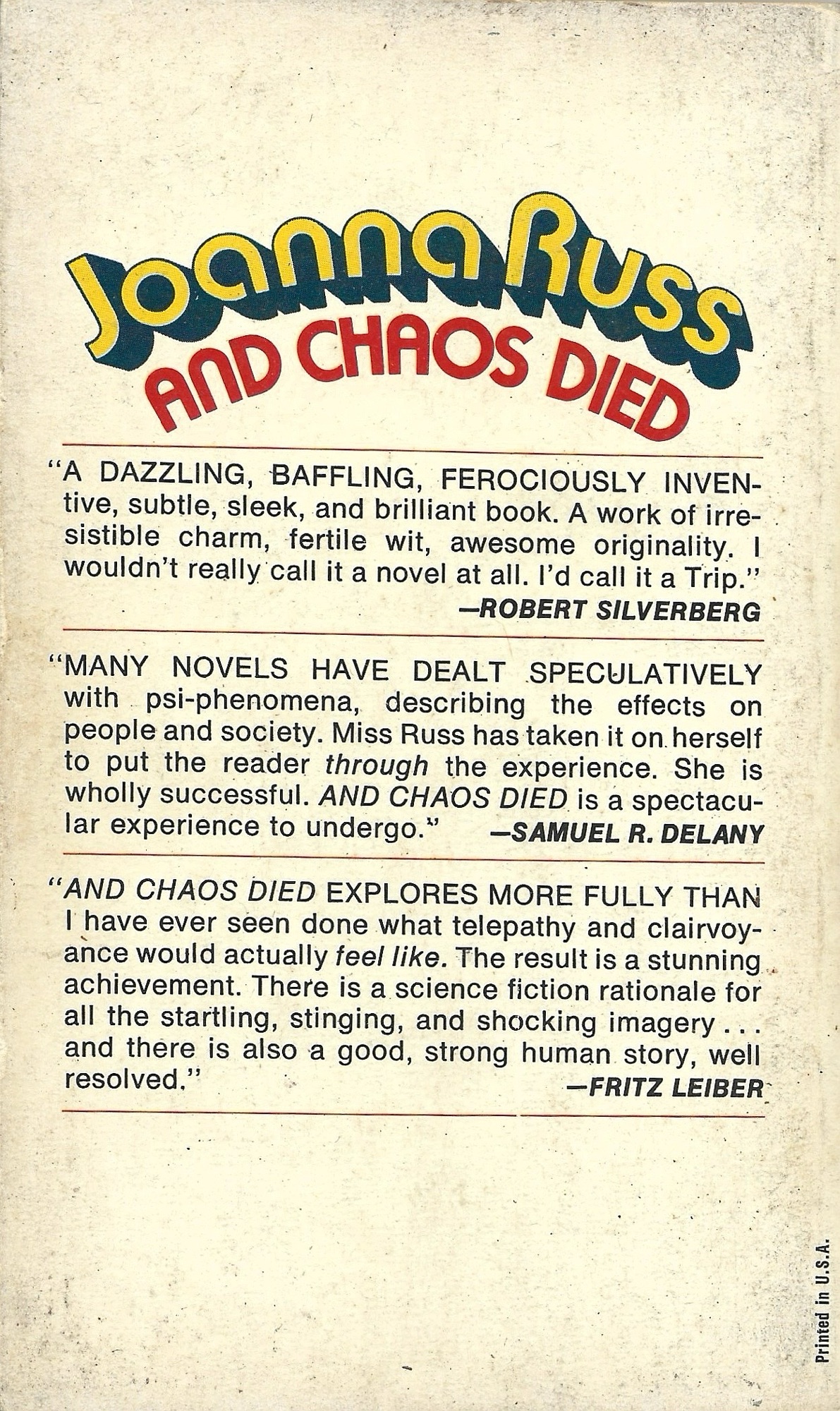

And Chaos Died, Joanna Russ, 1970. Ace Books (n.d., c. 1978). No cover artist or designer credited. 189 pages.

From Samuel R. Delany’s review of And Chaos Died:

The first two pages of this hardcover reprint of And Chaos Died present the protagonist, Jai Vedh, as a quietly despairing modern man with a nearly psychotic desire to merge with the universe. Moreover, it is suggested that this essentially religious desire is a response to the meaninglessness and homogeneity of every day life. There is a vacuum inside him; and when, on a business trip in a spaceship that has taken him off the surface of Old Earth (“on which every place was like every other place, ” p. 9), he senses the great vacuum of space itself about the ship, the real vacuum and the psychological vacuum become confused. Propelled by his desire for mergence,

on the nineteenth day he threw himself against one of the portals, flattening himself as if in immediate collapse, the little cousin he had lived with all his life become so powerful in the vicinity of its big relative that he could not bear it. Everything was in imminent collapse. He was found, taken to sick bay, and shot full of sedatives. They told him, as he went under, that the space between the stars was full of light, full of matter — what was it someone had said, an atom in a cubic yard? — and so not such a bad place after all. He was filled with peace, stuffed with it, replete; the big cousin was trustworthy.

Then the ship exploded. (p. 10)

The place Jai Vedh comes to, along with the philistine captain of the exploded spaceship, is the first of Russ’s SF utopias. Noting the January 1970 publishing date on the original edition, and thus inferring 1968/1969 as the most probable time of composition, we may be tempted to read this particular utopia as a kind of arcadian fall-out of that decade’s ecological crusade. A more sensitive reader of SF will, however, notice its sources in SF works that substantially predate that crusade: the nameless planet of telepaths takes its form from Clarke’s Lys (the more ruralized companion city to mechanical Diaspar in The City and the Stars, 1953) and from the world in Theodore Sturgeon’s “The Touch of Your Hand” ( 1953). What characterizes this particular SF image is not rural technology, but advanced technology hidden behind a rural facade; not human communication in good faith, but ordinarily invisible communicational pathways (some form of ESP); and it is always left and then returned to.