Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another takes Thomas Pynchon’s 1990 novel Vineland and sets it ablaze, reshaping its abstract paranoia and fractured narrative into something both deliriously immediate and ominously timeless.

The bones of Pynchon’s original are still present: a family broken by state violence; a daughter growing up without a mother; a father caught between shame and reluctant resistance. In PTA’s feverish recasting of Vineland, Zoyd Wheeler becomes Bob Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio), a former “Rocket Man” revolutionary burning out the past in a haze of weed smoke. Frenesi Gates is reimagined as Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor), a revolutionary addicted to the sexual thrill of power. Prairie Wheeler morphs into Willa (Chase Infiniti — and like wow jeez that’s a Pynchonian name the young actress has there, isn’t it?). And villainous Brock Vond is warped into Colonel Lockjaw (Sean Penn), a grotesque embodiment of authoritarian menace. Timelines collapse into themselves, Reagan-era dread transposes into our own disturbed now. Vineland is set in 1984; in One Battle After Another, PTA shows that we’ve never really moved on from that dystopian year. PTA condenses Vineland’s sprawling flashbacks and absurd digressions into an action-forward narrative that’s far more linear yet equally dizzying. The result is enthralling.

The film’s plot might be distilled simply from its title. One Battle After Another follows the trajectory of most of Pynchon’s fiction: individual resistance to authoritarian evil. In PTA’s film, that resistance takes the form of the French 75, a loose clandestine revolutionary group to which Bob and his partner Perfidia once belonged. There’s really no retiring for French 75 agents though, and soon Willa is tangled in the same web her parents sought to sunder in their radical actions. Penn’s maniacal Colonel Lockjaw hunts her down. She’s on the run, and so is papa Bob.

Pynchon’s novels frequently contrast Us vs Them systems — preterite vs. elect; misfits vs. authoritarians; freaks vs. the Man. And like Pynchon’s work, One Battle After Another shows the invisible overlapping and hierarchical confusions these Us/Them systems engender. The French 75’s sympathies directly correlate with the values of the immigrant community in Baktan Cross, the fictional sanctuary city Bob and Willa take refuge in. The de facto leader of these immigrants, Francisco (Benicio Del Toro), aids Bob in his fevered search for Willa. Francisco’s zen calm offers a counterbalance to Bob’s mania. Another Us group are the Sisters of the Brave Beaver (One Battle After another is crammed with Pynchonian vagina jokes), weed-growing nuns who offer Willa a brief safe harbor.

These disparate pockets of rebellion resist the tyranny of the modern racist capitalist system, embodied by Colonel Lockjaw and the military forces he commands (seemingly without any government oversight). We first meet Lockjaw running a migrant detention center — one of many timely PTA updates to Vineland — and his weird, forced, masochistic machismo plays out on the screen with a mix of menace and despair. For all his power and evil though, there’s yet another Them he isn’t part of. That would be the Christmas Adventurers Club, a shadowy cabal of elites on a racist mission to rid the world of “freaks.” Lockjaw would do quite literally anything to become a member of this club; his drive to to become even more Them propels the narrative while showing that Us-Them systems rely on hierarchies to perpetuate oppression.

One Battle After Another zigzags through a whirlwind of absurdity, suffocating paranoia, and frantic action. The film balances chaotic humor with a darker exploration of the emotional impulses that underlie power and attraction. Colonel Lockjaw’s obsessive fixation on Perfidia (arguably the film’s closest connection to Vineland) underscores the irrational power dynamics of obsession and control. PTA frames their relationship—along with Lockjaw’s obsession with Willa—as a twisted mirror reflecting the power imbalances that define both the personal and the political in Us-Them systems. PTA’s films have always explored systems of exploitation that grind people down and the outsiders who try to navigate them; One Battle After Another is, thus far, his most sustained, howling effort in this vein.

The film is gorgeous, too, as fans would expect from PTA. Michael Bauman’s cinematography conveys frenzied energy without sacrificing cohesion or clarity. There are several outstanding set pieces, including a beautiful sequence in which Bob does his best to keep up with a trio of skateboarders traversing rooftops at night, their figures silhouetted against the flames of a riot below. The film’s climactic three-car chase scene is particularly magnificent, its every twist and turn symbolizing not just physical pursuit, but deeper spirals of control, conflict, and paranoia. It made me physical ill. (That’s high praise.)

And while, yes, One Battle After Another is a bona fide action film, it’s still larded with strange little morsels that we’d expect from a PTA film — the image of Lockjaw licking his comb before taking it to his hair, his face contorted in anxious hope, or Bob, in his threadworn bathrobe, shoplifting a pair of cheap sunglasses. (Parenthetically, while the bathrobe is on my mind — Battle plays as a sinister inversion to The Big Lebowski. I will file the pair away for a future double feature.) One of the film’s funniest moments comes from Willa, who, despite being apparently subjugated by Lockjaw, nevertheless delivers the kind of crushing blow that can only come from a teen: “Why is your shirt so tight?” Indeed, Chase Infiniti’s portrayal of Willa is a revelation. In a movie crammed with paranoia and plot twists, she imbues in Willa a kind of moral force. She’s not an anchor exactly, because nothing is steady here. But maybe she’s the string you follow through the labyrinth.

One Battle After Another is almost three hours long, but it never drags, thanks to the tight direction and enthralling plot. Long-time PTA collaborator Jonny Greenwood’s score also keeps the film moving at a quick pace. The score is ever-present — something that usually irritates me in a film — but here the music provides emotional cohesion. It’s also just really fucking pretty. Frenetic drumming and altered pianos meet up with swelling strings that suggest sirens, banshees. Take “Mean Alley,” for example, which initially greets the ear as if the guitar is out of tune, but then coheres into beautiful dissonance. And although Greenwood’s wall-to-wall score leaves little room for the needle drops we might expect from a PTA joint, the film deploys Tom Petty’s “American Girl” in a moment of transcendent bliss that brought a tear to my eye.

Pynchon has always soundtracked his novels. Pynchonwiki gives close to 400 musical references for Vineland, but I don’t think any of these tracks ended up in One Battle After Another. My giving this data is a weak way of transitioning to the sentence, This is a film inspired by Vineland, not an adaptation of it. And while PTA captures the soul of the book, the vibe, or spirit, or whatever you like to call it, is decidedly different: darker, edgier, uglier. He captures the same strange humor and frustration of Vineland, but it’s amplified here with a chaotic energy that matches our current moment.

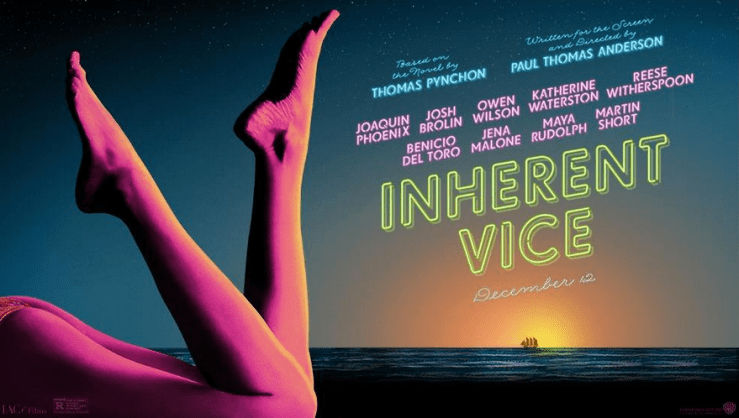

It’s also instructive to compare One Battle After Another to PTA’s earlier Pynchon adaptation, Inherent Vice. While Inherent Vice was a hazy sunsoaked journey through the disorienting aftereffects of the muddled sixties, One Battle After Another feels darker, more urgent, as if the timeline of history has compressed itself into an unyielding present. Both films deal with the fracturing of the American dream, but One Battle After Another does so with a sharper edge, drawing clearer political parallels. In some ways, PTA’s Inherent Vice is closer to Pynchon’s Vineland in tone and theme, less angular, more forgiving.

With both of his Pynchon films, PTA foregrounds a sweet final note, a belief in love as a sustaining force against Them. To borrow my favorite lines from Pynchon’s opus Gravity’s Rainbow: “They are in love. Fuck the war.” In his adaptation of Inherent Vice, PTA pulled a loose thread from the novel to neatly weave back into a prettier picture. He allows Doc Sportello to restore the heroin-addicted musician Coy to his family. One Battle offers a similarly fractured, imperfect restoration of family, a rewriting of rat-sins answered on the ghost of radio waves. He cleans up Pynchon’s messiness, but doesn’t sacrifice the deep danger that underwrites radical love.

One Battle After Another feels dangerously prescient, or, more accurately, a diagnosis of the big ugly now. In PTA’s Inherent Vice, there was an underlying fractured partnership between Us and Them; weirdo Doc Sportello tried to find some kind of brotherhood of man with The Man, Detective Bigfoot. No humanity can be extended to Lockjaw — not even from the club that will refuse him. They are unforgiving of any perceived impurity. The themes of mass surveillance, state violence, and detention resonate deeply in today’s climate. The recent death of Assata Shakur—possibly one inspiration for Perfidia Beverly Hills—adds a haunting layer to the film’s exploration of systemic oppression, the ways in which the state seeks to control and erase voices of resistance. The political urgency is palpable, and will undoubtedly alienate a large section of the genpop normies that Warner Brothers has heavily advertised the film to. Some folks will always root for Them.

But fuck Them. One Battle After Another is a triumph, a dizzying, chaotic masterpiece that never loses its grip on the present—one battle after another, all too real, all too important. See it on the biggest screen you can.