The first century Roman poet Martial used the Latin word plagiarius to complain that another poet had kidnapped his verses.

Plagiarius: kidnapper, seducer, plunderer, one who kidnaps the child or slave of another.

Anglicized by Johnson in 1601.

Plagiary, adjective. 1. Stealing men; kidnapping. 2. Practicing literary theft.

Based on the Indo-European root *-plak, “to weave” (seen for instance in Greek plekein, Bulgarian “плета” pleta, Latin plectere, all meaning “to weave”).

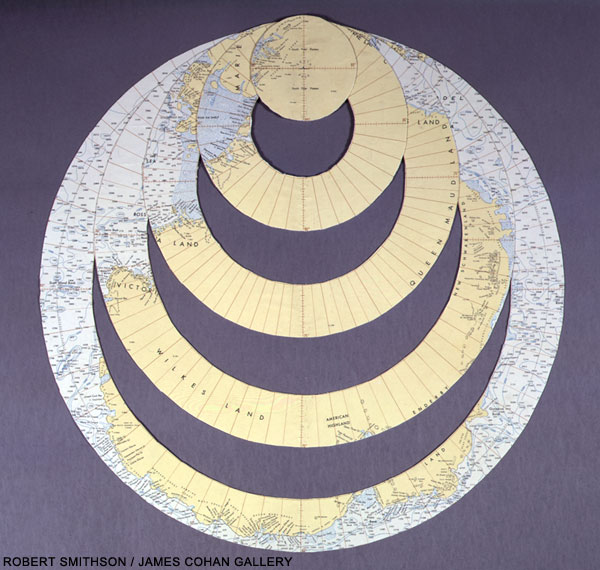

Listen Fates, who sit nearest of gods to the throne of Zeus, and weave with shuttles of adamant, inescapable devices for councels of every kind beyond counting.

Neith.

Frigg.

Brigantia.

If, while riding a horse overland, a man should come upon a woman spinning, then that is a very bad sign; he should turn around and take another way.

Wonderful, wonderful, yet again the sword of fate severs the head from the hydra of chance.

When shall we three meet again

In thunder, lightning, or in rain?

As we, or mother Dana, weave and unweave our bodies from day to day, their molecules shuttled to and fro, so does the artist weave and unweave his image.

In the 19th century there was a literary scandal when the leading Sterne scholar of the day discovered that many of the quintessentially Sternean passages of Tristram Shandy had been lifted from other authors.

Typically, a passage lamenting the lack of originality among contemporary writers was plagiarised from Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy.

Now academics call the plagiarism “intertextuality.”

When the hurlyburly’s done,

When the battle’s lost and won.

Urðr.

Verðandi.

Skuld.

Olaudah Equiano was born in 1745 in Eboe, in what is now Nigeria. When he was about eleven, Equiano was kidnapped and sold to slave traders headed to the West Indies.

When our women are not employed with the men in tillage, their usual occupation is spinning and weaving cotton, which they afterwards dye, and make it into garments.

“I did so, sir, for my sins,” said I; “for it was by his means and the procurement of my uncle, that I was kidnapped within sight of this town, carried to sea, suffered shipwreck and a hundred other hardships, and stand before you to-day in this poor accoutrement.”

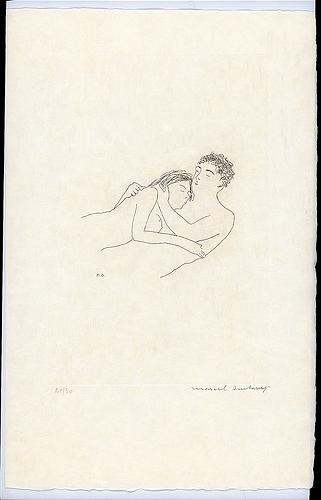

Persephone.

Europa.

Ganymede.

Plagiarism begins at home.

Nothing is said which has not been said before.

Originality: Judicious imitation.

Perhaps the efforts of the true poets, founders, religions, literatures, all ages, have been, and ever will be, our time and times to come, essentially the same—to bring people back from their present strayings and sickly abstractions, to the costless, average, divine, original concrete.

Hippolyta.

Helen.

Rapunzel.

I am against the prophets, saith the Lord, that steal My words every one from his neighbor.