1. This is one of the most extraordinary passages I’ve read so far in Pynchon’s Against the Day (pages 422-24 of my Penguin hardback).

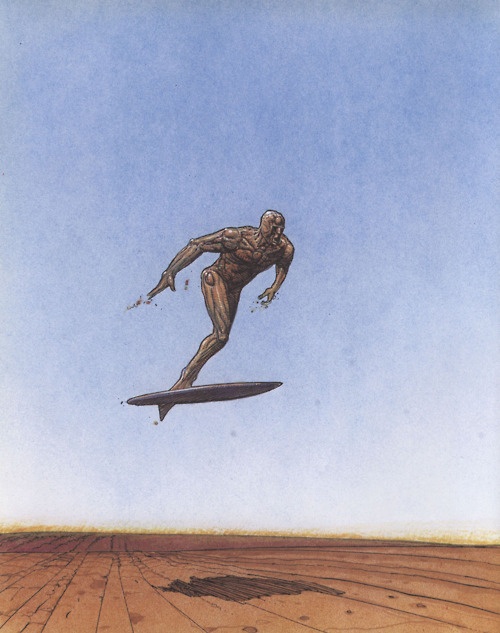

It comes almost at the end of Iceland Spar, the second of the AtD’s five books, working as a surreal, dream-logic climax to the chapter.

Our heroes the Chums of Chance experience an existential identity crisis, one that makes them wonder if they themselves were mere dreamers, readers of the dime novels that chronicled their adventures, and not, y’know, actual adventurers:

Meantime, now and then in the interstices of what was after all not a perpetual midwestern holiday, the former crew of the Inconvenience became aware of doubts creeping in. What if they weren’t harmonica players? really? If it was all just some elaborate hoax they’d chosen to play on themselves, to keep distracted from a reality too frightening to receive the vast undiscriminating light of the Sky, perhaps the not-to-be-spoken-of betrayal now firmly installed at the heart of the . . . the Organization whose name curiously had begun to escape them . . . some secret deal, of an unspecified nature, with an ancient enemy . . . but they could find no entries in any of the daily Logs to help them remember. . . .

Had they gone, themselves, through some mutation into imperfect replicas of who they once were? meant to revisit the scenes of unresolved conflicts, the way ghosts are said to revisit places where destinies took a wrong turn, or revisit in dreams the dreaming body of one loved more than either might have known, as if whatever happened between them could in that way be put right again? Were they now but torn and trailing afterimages of clandestine identities needed on some mission long ended, forgotten, but unwilling or unable to be released from it? Perhaps even surrogates recruited to stay behind on the ground, allowing the “real” Chums to take to the Sky and so escape some unbearable situation? None of them may really ever have been up in a skyship, ever walked the exotic streets or been charmed by the natives of any far-off duty station. They may only have once been readers of the Chums of Chance Series of boys’ books, authorized somehow to serve as volunteer decoys. Once, long ago, from soft hills, from creekside towns, from libraries that let kids lie on the floor where it’s cool and read the summer afternoons away, the Chums had needed them . . . they came.

WANTED Boys for challenging assignments, must be fit, dutiful, ready, able to play the harmonica (“At a Georgia Camp Meeting” in all keys, modest fines for wrong notes), and be willing to put in long hours of rehearsal time on the Instrument. . . Adventure guaranteed!

So that when the “real” Chums flew away, the boys were left to the uncertain sanctuary of the Harmonica Marching Band Training Academy. . . . But life on the surface kept on taking its usual fees, year by year, while the other Chums remained merrily aloft, kiting off tax-free to assignments all over the world, perhaps not even remembering their “deps” that well anymore, for there was so much to occupy the adventurous spirit, and the others— “groundhogs” in Chums parlance—had known, surely, of the risks and the costs of their surrogacy. And some would drift away from here as once, already long ago, from their wholesome heartland towns, into the smoke and confusion of urban densities unimagined when they began, to join other ensembles playing music of the newer races, arrangements of Negro blues, Polish polkas, Jewish klezmer, though others, unable to find any clear route out of the past, would return again and again to the old performance sites, to Venice, Italy, and Paris, France, and the luxury resorts of old Mexico, to play the same medleys of cakewalks and rags and patriotic airs, to sit at the same café tables, haunt the same skeins of narrow streets, gaze unhappily on Saturday evenings at the local youngsters circulating and flirting through the little plazas, unsure whether their own youth was behind them or yet to come. Waiting as always for the “true” Chums to return, longing to hear, “You were splendid, fellows. We wish we could tell you about everything that’s been going on, but it’s not over yet, it’s at such a critical stage, and the less said right now the better. But someday . . .”

“Are you going away again?”

“So soon?”

“We must. We’re just so sorry. The reunion feast was delicious and much appreciated, the harmonica recital one we shall never forget, especially the ‘coon’ material. But now . . .”

So, once again, the familiar dwindling dot in the sky.

“Don’t be blue, pal, it must’ve been important, they really wanted to stay this time, you could tell.”

“What are we going to do with all this extra food?”

“And all the beer nobody drank!”

“Somehow I don’t think that’ll be a problem.”

But that was the beginning of a certain release from longing, as if they had been living in a remote valley, far from any highways, and one day noticed that just beyond one of the ridge-lines all this time there’d been a road, and down this road, as they watched, came a wagon, then a couple of riders, then a coach and another wagon, in daylight which slowly lost its stark isotropy and was flowed into by clouds and chimney smoke and even episodes of weather, until presently there was a steady stream of traffic, audible day and night, with folks beginning to venture over into their valley to visit, and offering rides to towns nearby the boys hadn’t even known existed, and next thing anybody knew, they were on the move again in a world scarcely different from the one they had left. And one day, at the edge of one of these towns, skyready, brightwork gleaming, newly painted and refitted and around the corner of a gigantic hangar, waiting for them, as if they had never been away, there was their ship the good old Inconvenience. And Pugnax with his paws up on the quarterdeck rail, tail going a mile a minute, barking with unrestrained joy.

2. Long passage, so short riff:

3. First (or third, if my enumeration is honest), let me point out that this passage recalls a similar identity transference that happened earlier in the novel to Reef Traverse when he reads a Chums of Chance novel.

4. Which, to rehash the point of the riff I linked to in point 3 above, is to say that the passage is very much about reader-identification, about the ways that we dream ourselves into the novels we read—that the places they occupy are very real.

So much of Against the Day is about doubling, about secret identities, secret powers, secret lives—the invisible (the word “invisible” pops up again and again and again in this book)—that we can lead these whole other lives in our imagination, and that books fuel these lives, etc.

5. This book of Against the Day is named for Iceland spar, a crystal with double-refraction properties. Earlier, the stage magician/minor character Luca Zombini (“Light Zombie”?) reveals that he’s actually split people into two versions of themselves (evidence of such doppelgangers are scattered throughout the novel) using the mineral in his shows.

When our Chums finally reassume the mantles of their “true identities” we’re told that “they were on the move again in a world scarcely different from the one they had left” — are these the same Chums, the same aircrew, the same adventurers? The adverb “scarcely” seems to work some strange magic here.

6. In any case, their loyal hound Pugnax identifies them as the real McCoy, his “tail going a mile a minute, barking with unrestrained joy.”

I’ll admit to feeling some of that joy myself.