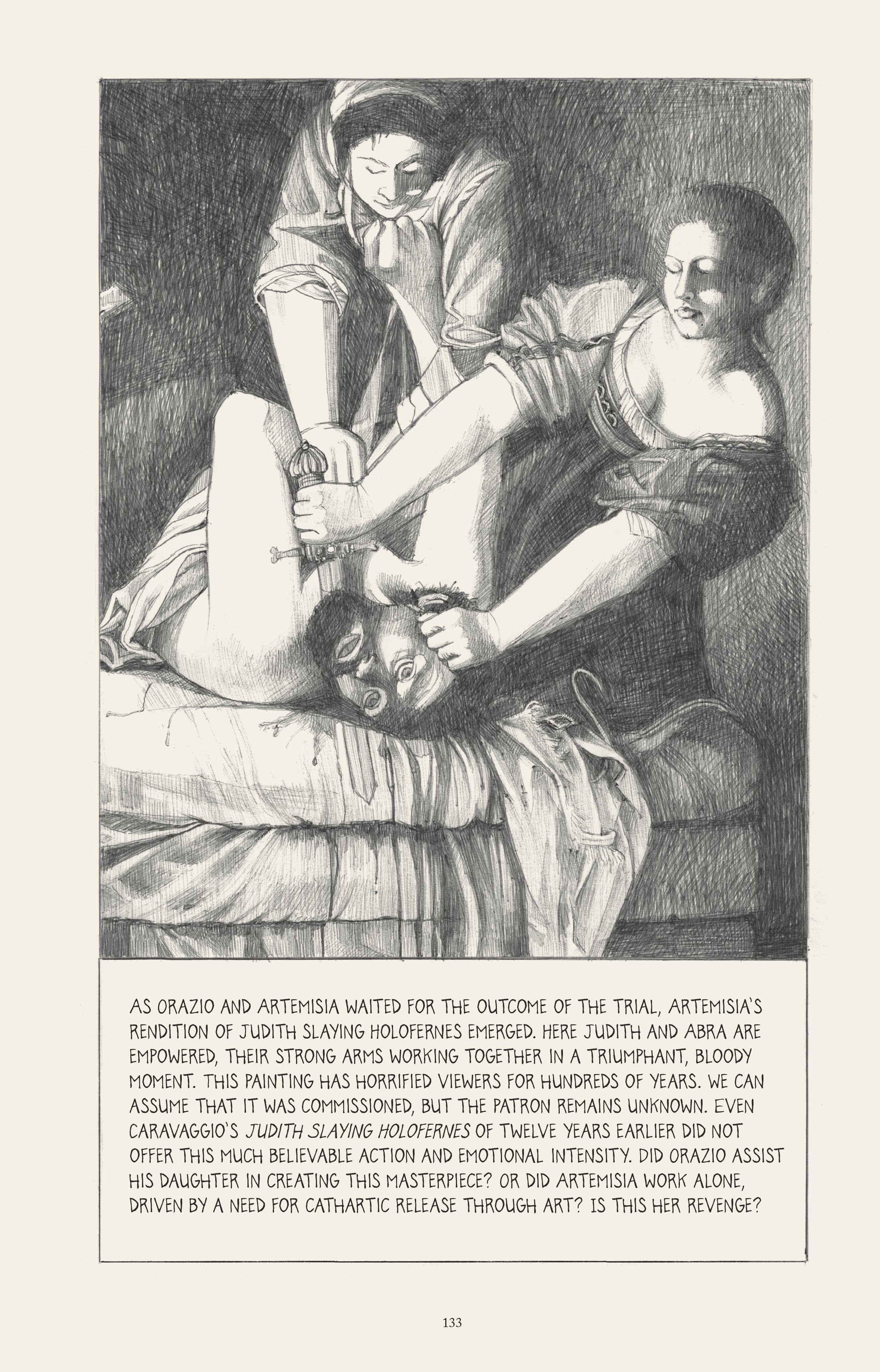

Judith Slaying Holofrenes (After Artemisia Gentileschi) by Gina Siciliano. From Siciliano’s brilliant biography, I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi.

Judith Slaying Holofrenes (After Artemisia Gentileschi) by Gina Siciliano. From Siciliano’s brilliant biography, I Know What I Am: The Life and Times of Artemisia Gentileschi.

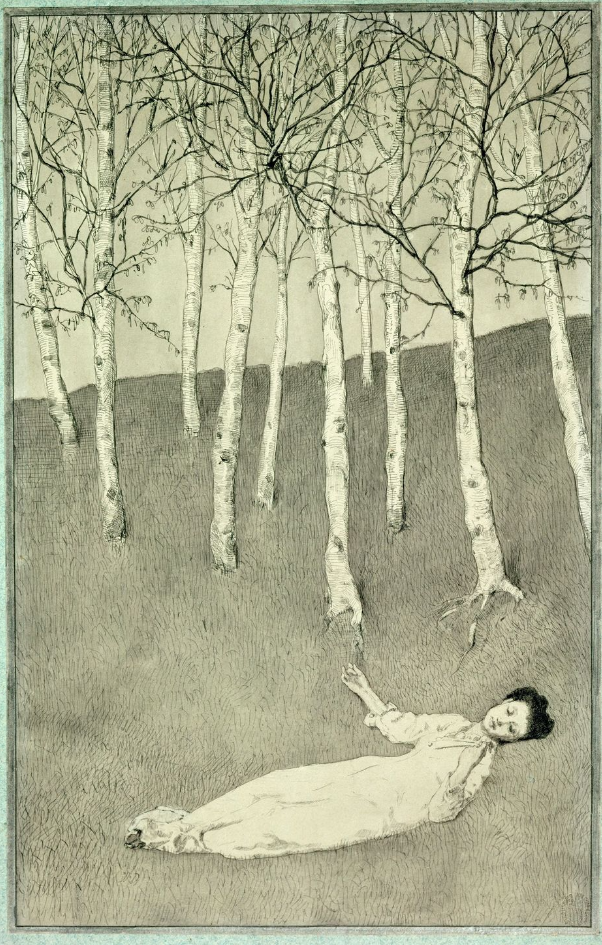

Night Walkers, 2022 by Salman Toor (b. 1983)

Seated Female Nude, c. 1933 by Ivan Albright (1897-1983)

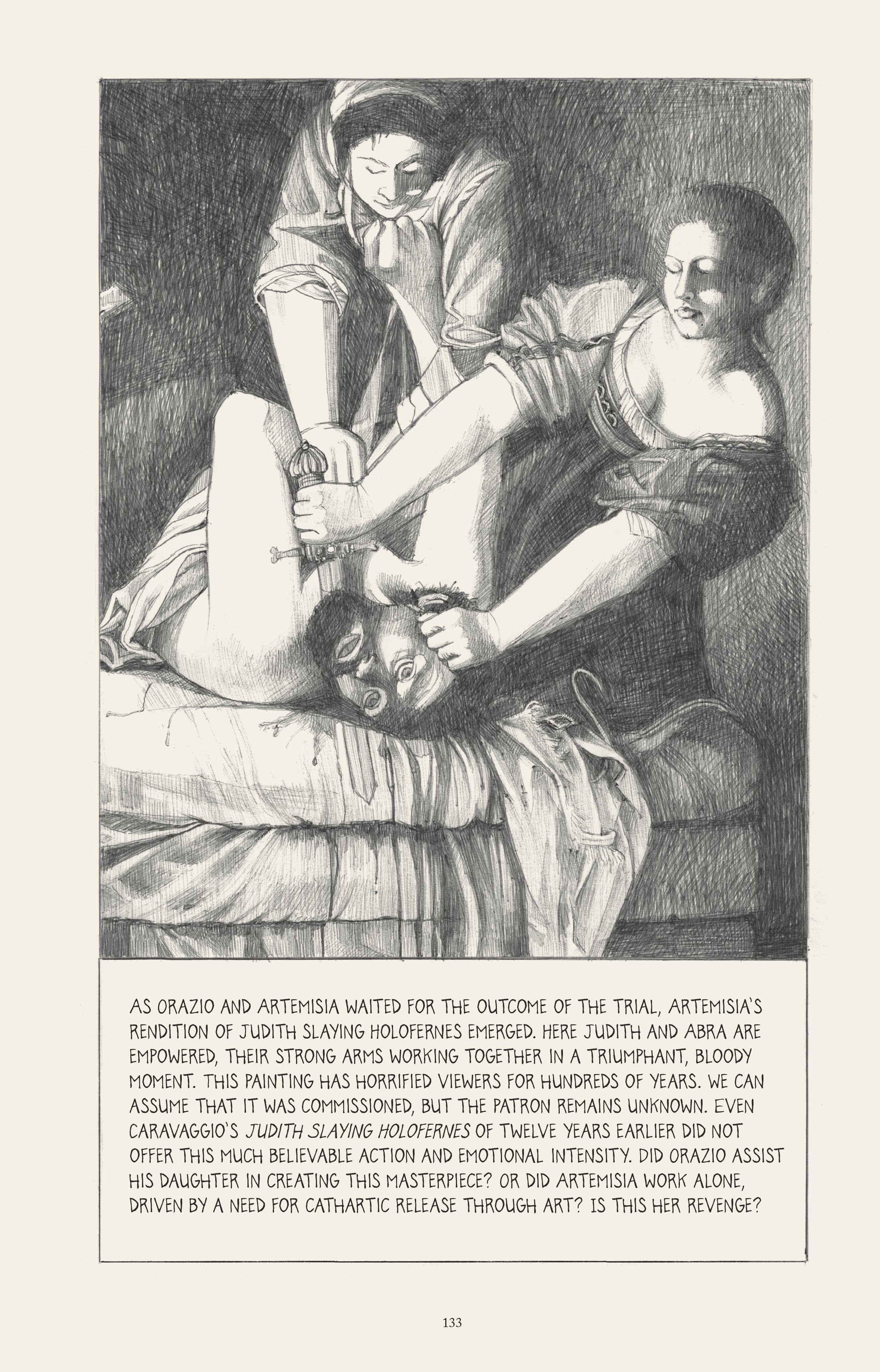

Near Miss, 2025 by Jed Webster Smith (b. 1992)

Make Way for the Head, 2024 by Lorenzo Tonda (b. 1992)

Untitled (illustration for “The Big Cats,” Esquire, April, 1961) by Milton Glaser (1929-2020)

Owl with Two Chicks Sitting on Branch, 1893 by Henry de Groux (1866–1930)

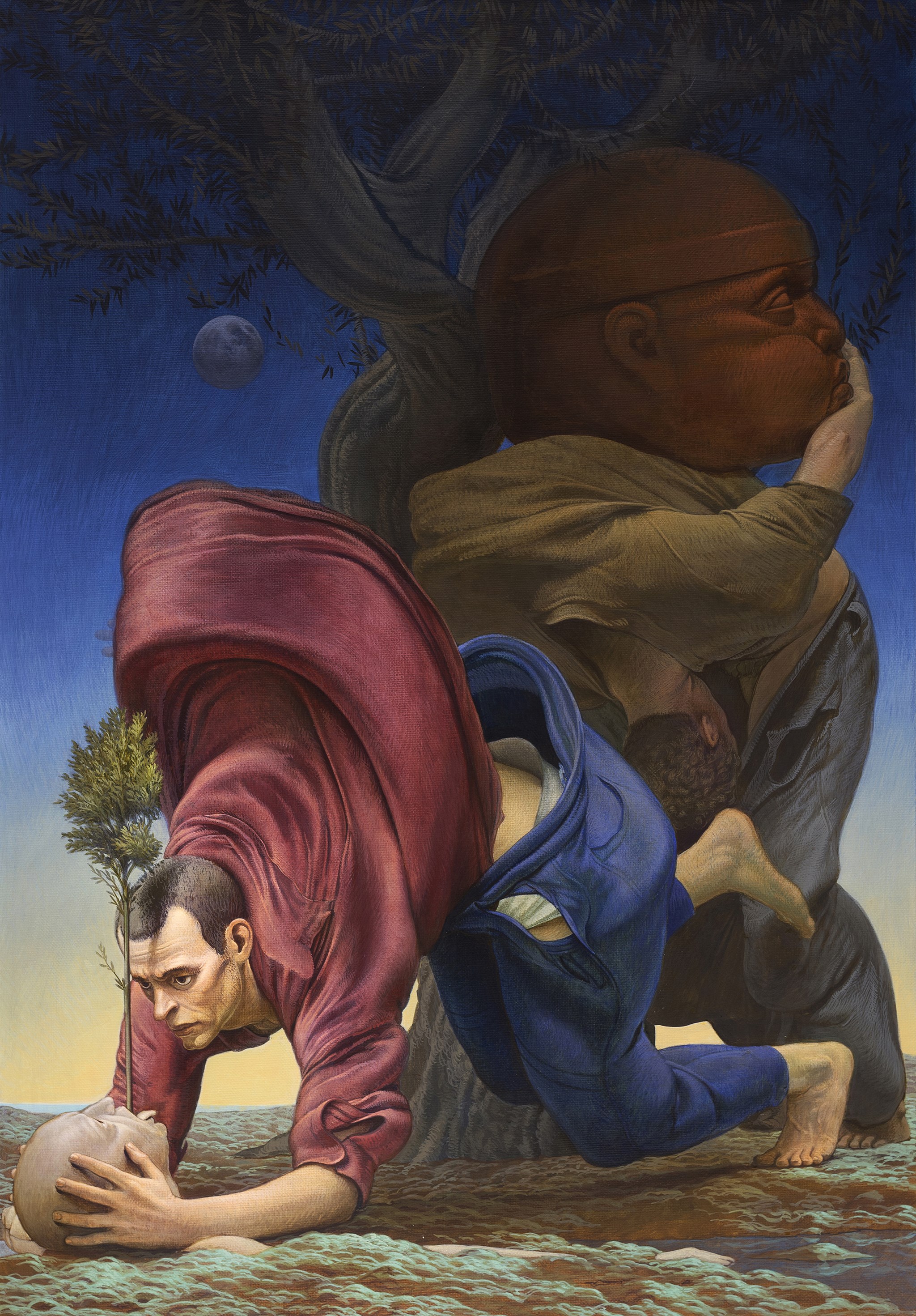

Early Spring, 1897 by Max Klinger (1857-1920)

Untitled, 2024 by Anas Albraehe (b. 1991)

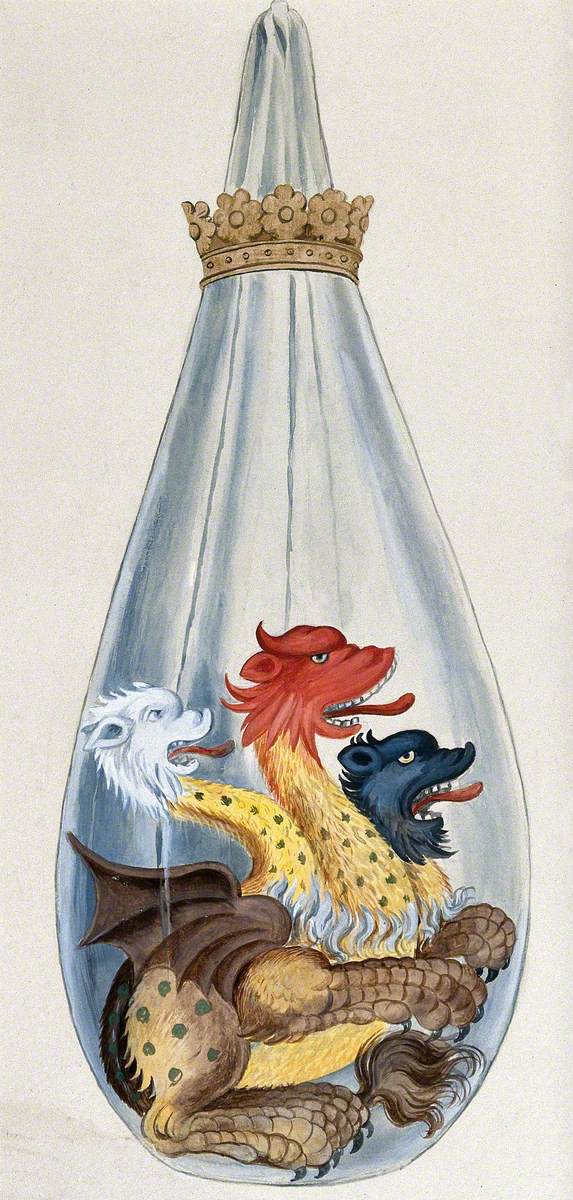

A Three-Headed Monster in an Alchemical Flask, Representing the Composition of the Alchemical Philosopher’s Stone: Salt, Sulphur, and Mercury, c. 1909 by Edith A. Ibbs (1863–1937).

A decade ago I finally tossed out most of the contents of an old shoebox crammed with high-school nostalgia. Notes from ex-girlfriends, summer postcards, flyers from local shows, a handful of choice mixtapes. Some Polaroids. Our stupid band’s stupid lyrics, which we usually forgot or simply abandoned live. There was even a pair of fat shoelaces. The pain of return always hits me hard at such times, and I got dizzy. That box was crammed the scraps of an older life.

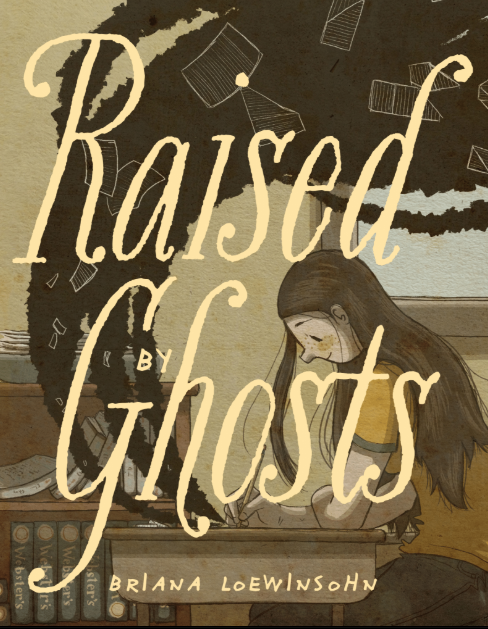

The preceding paragraph is an unfair opening to a review of Briana Loewinsohn’s excellent graphic memoir Raised by Ghosts. Reading Raised by Ghosts felt like opening that old shoebox: painful, dizzying, beautiful. Loewinsohn is one of us, one of us to borrow a chant from Tod Browning’s Freaks. “Sometimes I feel like I am an alien at this school…But there are other aliens here,” protagonist Briana writes in her diary.

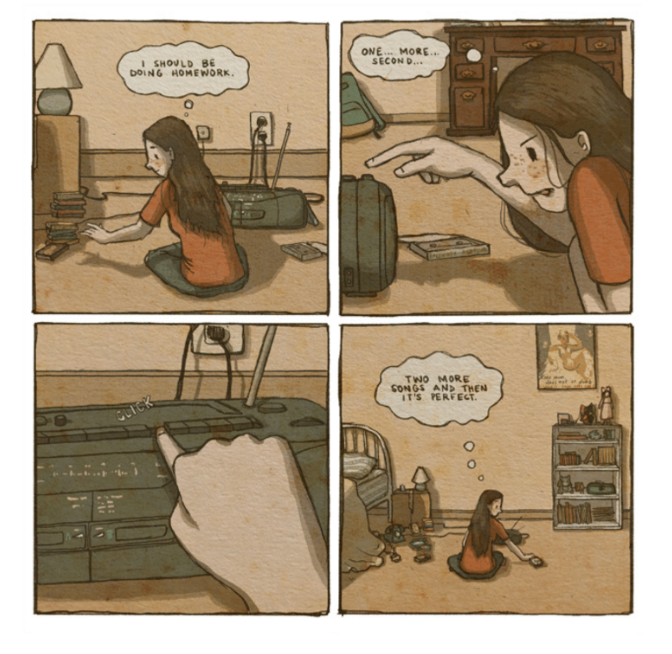

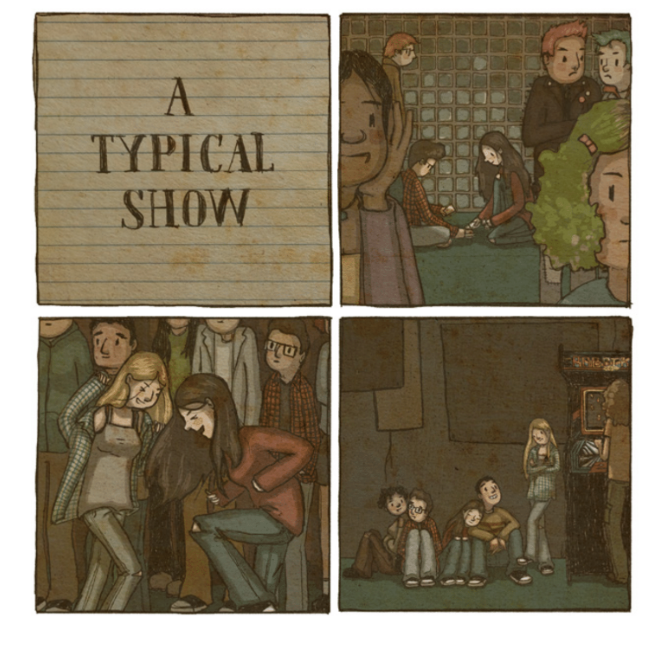

Raised by Ghosts covers Briana’s seven rough years through middle and high school. These are the gay nineties. The narrator, like Loewinsohn herself, is about my age, which makes reading Raised by Ghosts an eerie act of self-recognition. It’s not a conventional memoir—it doesn’t hold your hand or deliver a clean, linear narrative. Instead, it moves like memory does: in flashes, in vignettes, in small sensory moments that coalesce into something greater than the sum of their parts. Everything here feels true. We have here the relics of a teenage moondream, those little ghosts of the past that flicker through memory like frayed photos freed from the rubberbanded bundle in an old Converse box. Briana’s adolescence unfurls as an ebb and flow of loneliness and acceptance among fellow weirdos. She finds her people, but never quite makes the scene; she dances at the live show but finds as much fun in playing cards in the back.

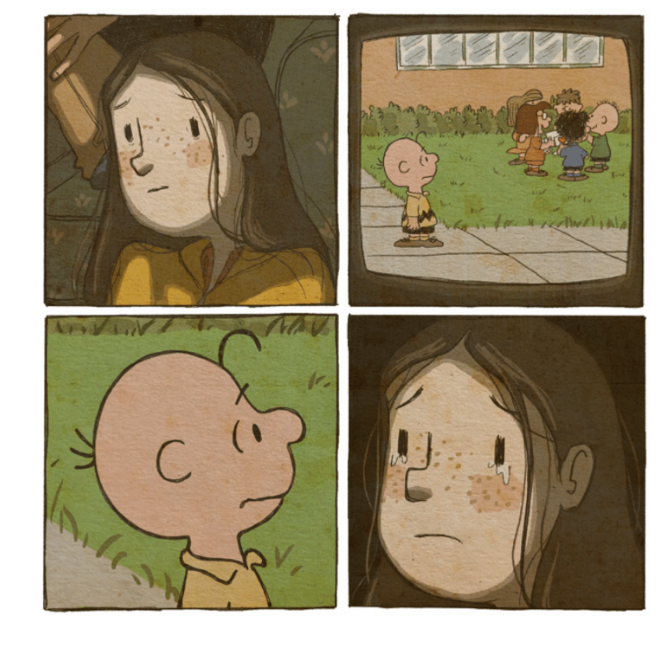

Loewinsohn’s art conveys Raised by Ghosts’ emotional weight. Soft, muted tones in drab olive and rust hues fill square panels that often resemble fading Polaroids. Candids and close-ups capture the messiness of high school. Briana is a sympathetic and endearing character, her sensitivity registering in ways she cannot understand herself, as when she skips out on a living-room VHS double feature. Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers would be way too much after the tragedy of You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown.

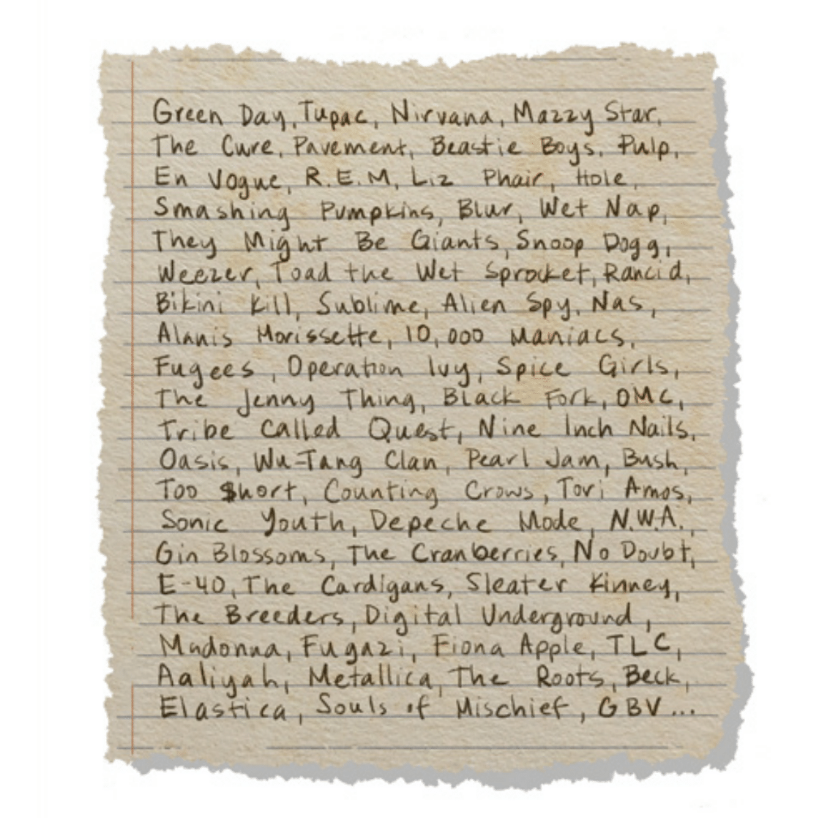

Loewinsohn includes full handwritten pages to accompany the traditional comic strips in Raised by Ghosts. These handwritten pages serve as a kind of diary, but often take on subtle visual changes that suggest other media. Often, the handwritten pages mimic the form of the long notes bored Briana composes in class to pass to friends. A passage composed on graph paper praises the note-writing skills of a particular friend; the technique suggests this friend prefers squares to lines. A passage on a brown paper lunch bag reflects on how Briana’s father always takes the time to write her name in detailed, expressive lettering. The variations of handwritten pages enrich the narrative and subtly inform us of Briana’s artistic development.

My favorite of the handwritten passages though is simply a list of bands scrawled on lined paper. When I got to that page, about a third of the way into Raised by Ghosts, I was already persuaded by the book–but the page of band names seemed so utterly true, so beautiful and banal. We used to do that, I thought, and: Why did we used to do that? knowing the answer has no good intellectual answer.

But let’s get to the ghosts. Loewinsohn never “shows” us Briana’s parents, yet the picture we get of them is hardly incomplete: a distant, detached mother and a father in arrested development. “I would say I was raised in an AA meeting,” Briana remarks of her mother, noting that it’s often hard for single mothers to find childcare. Of her father’s abode: “My pop’s house is a combination of Indiana Jones’ office, Pee Wee’s playhouse, and an opium den. I am kinda like a roommate here.”

Publisher Fantagraphics labels Raised by Ghosts as a “young adult graphic novel,” and teenagers will likely identify with Briana’s story—the loneliness, the search for belonging, the quiet acts of self-definition. They may also feel a strange twinge of envy for a world that no longer exists. Being a latchkey kid could be lonely, but it was not without its freedoms. Those of us who were teenage weirdos in the nineties will see in Loewinsohn’s memoir not a young adult novel, but rather a reflective elegy composed by a mature artist in control of her talent. Raised by Ghosts lingers like the echo of an old song in your dim memory — you know the one, right? It’s a memoir about growing up in the margins, about finding meaning in scraps and silence, about turning absence into something tangible. It haunts, in the very best way.

The Fool, 1955 by Leonora Carrington (1917 – 2011)

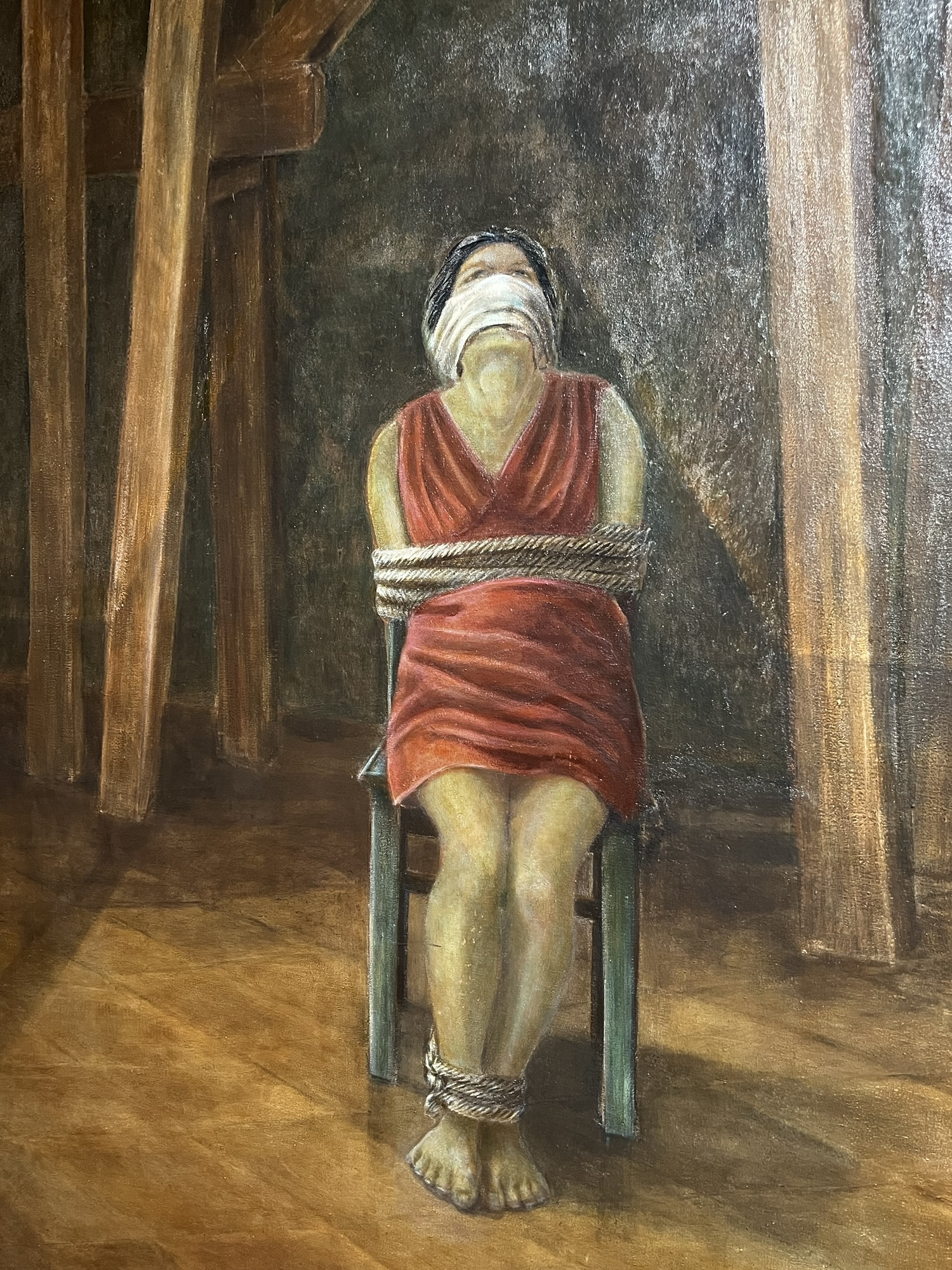

The Wait (Detail) 1980 by María Teresa Morán (1939-2017)

Propaganda III, 2022 by Chen Ching-Yuan (b. 1984)

Fleeing Man, 1965 by Leon Golub (1922-2004)