- A girl’s lover to be slain and buried in her flower-garden, and the earth levelled over him. That particular spot, which she happens to plant with some peculiar variety of flowers, produces them of admirable splendor, beauty, and perfume; and she delights, with an indescribable impulse, to wear them in her bosom, and scent her chamber with them. Thus the classic fantasy would be realized, of dead people transformed to flowers.

- Objects seen by a magic-lantern reversed. A street, or other location, might be presented, where there would be opportunity to bring forward all objects of worldly interest, and thus much pleasant satire might be the result.

- A missionary to the heathen in a great city, to describe his labors in the manner of a foreign mission.

- To show the effect of gratified revenge. As an instance, merely, suppose a woman sues her lover for breach of promise, and gets the money by instalments, through a long series of years. At last, when the miserable victim were utterly trodden down, the triumpher would have become a very devil of evil passions,–they having overgrown his whole nature; so that a far greater evil would have come upon himself than on his victim.

Category: Literature

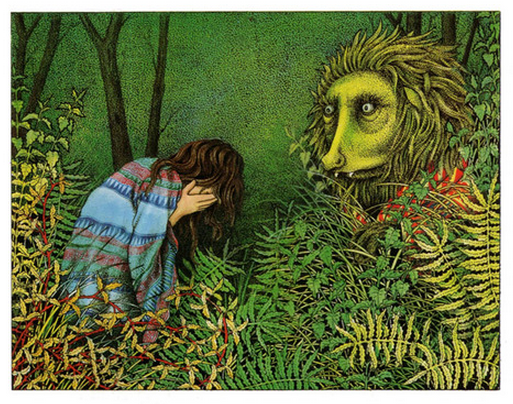

Beauty and the Beast — Alan Baker

“The conventional means of attaining the castle” (Donald Barthelme)

80. The conventional means of attaining the castle are as follows: “The eagle dug its sharp claws into the tender flesh of the youth, but he bore the pain without a sound, and seized the bird’s two feet with his hands. The creature in terror lifted him high up into the air and began to circle the castle. The youth held on bravely. He saw the glittering palace, which by the pale rays of the moon looked like a dim lamp; and he saw the windows and balconies of the castle tower. Drawing a small knife from his belt, he cut off both the eagle’s feet. The bird rose up in the air with a yelp, and the youth dropped lightly onto a broad balcony. At the same moment a door opened, and he saw a courtyard filled with flowers and trees, and there, the beautiful enchanted princess.” (The Yellow Fairy Book)

From Donald Barthelme’s short story “The Glass Mountain” (read it here).

National Day of Encouragement Reading List

Today, a dollar store calendar my grandmother gave me tells me, is National Day of Encouragement, which is totally a real thing. So here is a National Day of Encouragement Reading List, which is also totally a real thing. Much encouragement to you, citizens!

- King Lear, William Shakespeare

- Blood Meridian, Cormac McCarthy

- “Before the Law,” Franz Kafka

- Candide, Voltaire

- First Love and Other Sorrows, Harold Brodkey

- “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” Nathaniel Hawthorne

- Camp Concentration, Thomas Disch

- “The Lottery,” Shirley Jackson

- “The Raven,” Edgar Allan Poe

- The Awakening, Kate Chopin

- Things Fall Apart, Chinua Achebe

- The Bell Jar, Sylvia Plath

- Correction, Thomas Bernhard

- Butterfly Stories, William Vollmann

- “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” Flannery O’Connor

- The Road, Cormac McCarthy

- 2666, Roberto Bolaño

- “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Edgar Allan Poe

- Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë

- From Hell, Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell

- The Flame Alphabet, Ben Marcus

- The Painted Bird, Jerzy Kosinski

- Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad

- “The Wasteland,” T.S. Eliot

- Hamlet, William Shakespeare

- The Pearl, John Steinbeck

- Distant Star, Roberto Bolaño

- Notes from Underground, Fyodor Dostoyevsky

- The Yearling, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

- The Kindly Ones, Jonathan Littell

- “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” Flannery O’Connor

- Gargoyles, Thomas Bernhard

- The Plague, Albert Camus

- “The Yellow Wallpaper,” Charlotte Perkins Gilman

- Frankenstein, Mary Shelley

- Where the Red Fern Grows, Wilson Rawls

- A Farewell to Arms, Ernest Hemingway

- “Good Old Neon,” David Foster Wallace

- 1984, George Orwell

- Nausea, Jean-Paul Sartre

Melville Underwater Camera

From David Wiesner’s marvelous wordless wonder book Flotsam.

“A Note on Realism” — Robert Louis Stevenson

“A Note on Realism” by Robert Louis Stevenson

Style is the invariable mark of any master; and for the student who does not aspire so high as to be numbered with the giants, it is still the one quality in which he may improve himself at will. Passion, wisdom, creative force, the power of mystery or colour, are allotted in the hour of birth, and can be neither learned nor simulated. But the just and dexterous use of what qualities we have, the proportion of one part to another and to the whole, the elision of the useless, the accentuation of the important, and the preservation of a uniform character from end to end—these, which taken together constitute technical perfection, are to some degree within the reach of industry and intellectual courage. What to put in and what to leave out; whether some particular fact be organically necessary or purely ornamental; whether, if it be purely ornamental, it may not weaken or obscure the general design; and finally, whether, if we decide to use it, we should do so grossly and notably, or in some conventional disguise: are questions of plastic style continually rearising. And the sphinx that patrols the highways of executive art has no more unanswerable riddle to propound.

In literature (from which I must draw my instances) the great change of the past century has been effected by the admission of detail. It was inaugurated by the romantic Scott; and at length, by the semi-romantic Balzac and his more or less wholly unromantic followers, bound like a duty on the novelist. For some time it signified and expressed a more ample contemplation of the conditions of man’s life; but it has recently (at least in France) fallen into a merely technical and decorative stage, which it is, perhaps, still too harsh to call survival. With a movement of alarm, the wiser or more timid begin to fall a little back from these extremities; they begin to aspire after a more naked, narrative articulation; after the succinct, the dignified, and the poetic; and as a means to this, after a general lightening of this baggage of detail. After Scott we beheld the starveling story—once, in the hands of Voltaire, as abstract as a parable—begin to be pampered upon facts. The introduction of these details developed a particular ability of hand; and that ability, childishly indulged, has led to the works that now amaze us on a railway journey. A man of the unquestionable force of M. Zola spends himself on technical successes. To afford a popular flavour and attract the mob, he adds a steady current of what I may be allowed to call the rancid. That is exciting to the moralist; but what more particularly interests the artist is this tendency of the extreme of detail, when followed as a principle, to degenerate into merefeux-de-joie of literary tricking. The other day even M. Daudet was to be heard babbling of audible colours and visible sounds. Continue reading ““A Note on Realism” — Robert Louis Stevenson”

Five from Félix Fénéon

“The only form of discourse” (Donald Barthelme)

“The only form of discourse of which I approve,” Miss R. said in her dry, tense voice, “is the litany. I believe our masters and teachers as well as plain citizens should confine themselves to what can safely be said. Thus when I hear the words pewter, snake, tea, Fad #6 sherry, serviette, fenestration, crown, blue coming from the mouth of some public official, or some raw youth, I am not disappointed. Vertical organisation is also possible,” Miss R. said, “ as in

pewter

snake

tea

fad #6 sherry

serviette

fenestration

crown

blue.

I run to liquids and colours,” she said, “but you, you may run to something else, my virgin,’ my darling, my thistle, my poppet, my own. Young people,” Miss R. said, “run to more and more unpleasant combinations as they sense the nature of our society. Some people,” Miss R. said, “run to conceits or wisdom but I hold to the hard, brown, nutlike word. I might point out that there is enough aesthetic excitement here to satisfy anyone but a damned fool.” I sat in solemn silence.

From Donald Barthelme’s short story “The Indian Uprising”; read the full story.

“Childhood is still running along beside us like a little dog” (Thomas Bernhard)

“Childhood is still running along beside us like a little dog who used to be a merry companion, but who now requires our care and splints, and myriad medicines, to prevent him from promptly passing on.” It went along rivers, and down mountain gorges. If you gave it any assistance, the evening would construct the most elaborate and costly lies. But it wouldn’t save you from pain and indignity. Lurking cats crossed your path with sinister thoughts. Like him, so nettles would sometimes draw me into fiendish moments of unchastity. As with him, my fear was made palatable by raspberries and blackberries. A swarm of crows were an instant manifestation of death. Rain produced damp and despair. Joy pearled off the crowns of sorrel plants. “The blanket of snow covers the earth like a sick child.” No infatuation, no ridicule, no sacrifice. “In classrooms, simple ideas assembled themselves, and on and on.” Then stores in town, butchers’ shop smells. Façades and walls, nothing but façades and walls, until you got out into the country again, quite abruptly, from one day to the next. Where the meadows began, yellow and green; brown plowland, black trees. Childhood: shaken down from a tree, so much fruit and no time! The secret of his childhood was contained in himself. Growing up wild, among horses, poultry, milk, and honey. And then: being evicted from this primal condition, bound to intentions that went way beyond himself. Designs. His possibilities multiplied, then dwindled in the course of a tearful afternoon. Down to three or four certainties. Immutable certainties. “How soon it is possible to spot dislike. Even without words, a child wants everything. And attains nothing.” Children are much more inscrutable than adults. “Protractors of history. Conscienceless. Correctors of history. Bringers-on of defeat. Ruthless as you please.” As soon as it could blow its own nose, a child was deadly to anything it came in touch with. Often—as it does me—it gives him a shock, when he feels a sensation he had as a child, provoked by a smell or a color, but that doesn’t remember him. “At such a moment you feel horribly alone.”

From Thomas Bernhard’s novel Frost.

Facts, Questions, and Images from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Note-Books

- The Abyssinians, after dressing their hair, sleep with their heads in a forked stick, in order not to discompose it.

- At the battle of Edge Hill, October 23, 1642, Captain John Smith, a soldier of note, Captain Lieutenant to Lord James Stuart’s horse, with only a groom, attacked a Parliament officer, three cuirassiers, and three arquebusiers, and rescued the royal standard, which they had taken and were guarding. Was this the Virginian Smith?

- Stephen Gowans supposed that the bodies of Adam and Eve were clothed in robes of light, which vanished after their sin.

- Lord Chancellor Clare, towards the close of his life, went to a village church, where he might not be known, to partake of the Sacrament.

- In the tenth century, mechanism of organs so clumsy, that one in Westminster Abbey, with four hundred pipes, required twenty-six bellows and seventy stout men. First organ ever known in Europe received by King Pepin, from the Emperor Constantine, in 757. Water boiling was kept in a reservoir under the pipes; and, the keys being struck, the valves opened, and steam rushed through with noise. The secret of working them thus is now lost. Then came bellows organs, first used by Louis le Débonnaire.

- After the siege of Antwerp, the children played marbles in the streets with grape and cannon shot.

- A shell, in falling, buries itself in the earth, and, when it explodes, a large pit is made by the earth being blown about in all directions,–large enough, sometimes, to hold three or four cart-loads of earth. The holes are circular.

- A French artillery-man being buried in his military cloak on the ramparts, a shell exploded, and unburied him.

- In the Netherlands, to form hedges, young trees are interwoven into a sort of lattice-work; and, in time, they grow together at the point of junction, so that the fence is all of one piece.

From Nathaniel Hawthorne’s American Note-Books.

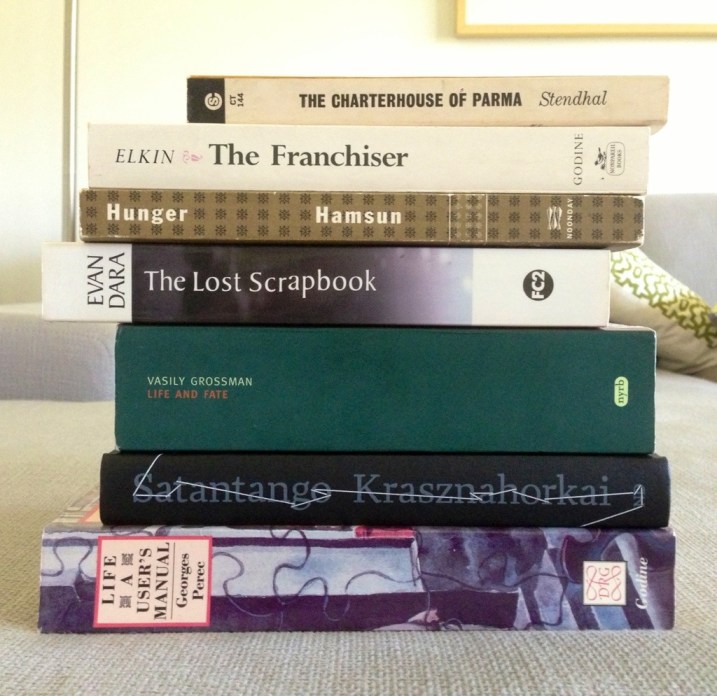

Biblioklept Is Seven Today, So Here are Seven Sets of Seven Somethings

*

Seven Reviews of Seven Books I Love

The Rings of Saturn — W.G. Sebald

Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams Is a Perfect Novella

The Pale King — David Foster Wallace

The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis

Intertexuality and Structure in Roberto Bolaño’s 2666

*

Seven Hands (Van Gogh)

*

Seven Books I’d Like to Read Sometime in the Next Seven Years

*

Seven Negative Reviews

Why I Abandoned Chad Harbach’s Over-Hyped Novel The Art of Fielding After Only 100 Pages

Jonathan Lethem’s Bloodless Prose

I Super Hated Gary Shteyngart’s Super Sad True Love Story

The Sot-Weed Factor — John Barth

*

Seven Ballerinas (Picasso)

*

Seven Perfect Short Stories

“The Death of Me” — Gordon Lish

“A Good Man Is Hard to Find” — Flannery O’Connor

“The School” — Donald Barthelme

“Wakefield” — Nathaniel Hawthorne

“Good Old Neon” — David Foster Wallace

*

Seven Deadly Sins (Bosch)

*

“A Drinking Song” — W.B. Yeats

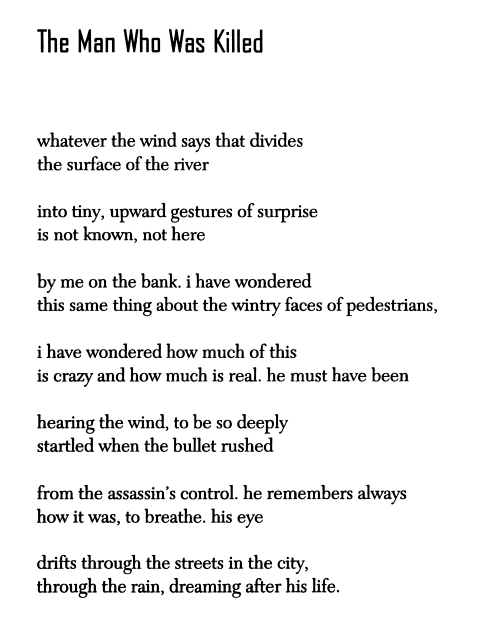

“The Man Who Was Killed” — Denis Johnson

Biblioklept’s Dictionary of Literary Terms

APHORISM

A concise, often witty, turn of phrase that should be shared out of context on Twitter or Pinterest.

BILDUNGSROMAN

Novel where someone (preferably male) matures into the ideal state of bitter disillusionment.

CATHARSIS

Evocation of fear and pity. Best exemplified in modern storytelling by Lifetime Network original movies.

DECONSTRUCTION

A form of textual analysis. No one knows what it means. Apply liberally.

EXISTENTIALIST

Use to describe any French novel of the 20th century. Serve with coffee and cigarettes.

FOIL

First, Outer, Inner, Last.

GENRE FICTION

Deride genre fiction at all times. If a writer uses genre tropes, praise her for genre bending. (See LITERARY FICTION).

HYSTERICAL REALISM

Use to describe any big ambitious novel that does not meet your aesthetic and/or moral needs.

IAMBIC PENTAMETER

All poetry is composed in iambic pentameter.

JUVENILIA

A writer’s immature work, which she usually (wisely) withholds from publication. After the writer dies, every scrap should be published, scrutinized, and passed around the internet out of context.

KAKFAESQUE

Synonym for “odd.” Apply freely.

LITERARY FICTION

A genre of fiction that pretends not to be a genre. What your book club is reading this month.

MAGICAL REALISM

Use to describe any novel by a South American writer.

NARRATOLOGY

Use structuralist techniques to analyze narrative plots—and watch the kids go wild! Narratology is the number one thing the audience of a book review is interested in.

ORPHAN

All heroes must be orphans.

PANOPTICON

Use this term liberally in any discussion of modern politics. Pairs well with film studies courses.

QUEER THEORY

A form of literary analysis that conveniently begins with the letter “Q,” making it ideal for silly alphabetized lists like this one.

ROUND CHARACTER

A character portrayed in psychological and emotional depth to the degree that she comes alive in your imagination. Round characters provide an excellent alternative to making meaningful human relationships.

SOUTHERN GOTHIC

Use to describe the style of any writer from the Southern part of the United States.

TAUTOLOGY

A tautology is a tautology.

UTOPIA

Synonym for dystopia. Argue about its pronunciation, indicating that you understand the complexities of Greek prefixes.

VERISIMILITUDE

Literary trickery.

WHODUNNIT

A genre of books that sells well in airports.

XENA

Beloved warrior princess. Look, x is hard, okay?

YOUNG WERTHER

The original sad bastard; he invented emo.

ZEITGEIST

Time’s ghost. You’re soaking in it, which makes it hard to see.

“The Hobo and the Fairy” — Jack London

“The Hobo and the Fairy” by Jack London

He lay on his back. So heavy was his sleep that the stamp of hoofs and cries of the drivers from the bridge that crossed the creek did not rouse him. Wagon after wagon, loaded high with grapes, passed the bridge on the way up the valley to the winery, and the coming of each wagon was like the explosion of sound and commotion in the lazy quiet of the afternoon.

But the man was undisturbed. His head had slipped from the folded newspaper, and the straggling, unkempt hair was matted with the foxtails and burrs of the dry grass on which it lay. He was not a pretty sight. His mouth was open, disclosing a gap in the upper row where several teeth at some time had been knocked out. He breathed stertorously, at times grunting and moaning with the pain of his sleep. Also, he was very restless, tossing his arms about, making jerky, half-convulsive movements, and at times rolling his head from side to side in the burrs. This restlessness seemed occasioned partly by some internal discomfort, and partly by the sun that streamed down on his face and by the flies that buzzed and lighted and crawled upon the nose and cheeks and eyelids. There was no other place for them to crawl, for the rest of the face was covered with matted beard, slightly grizzled, but greatly dirt-stained and weather-discolored.

The cheek-bones were blotched with the blood congested by the debauch that was evidently being slept off. This, too, accounted for the persistence with which the flies clustered around the mouth, lured by the alcohol-laden exhalations. He was a powerfully built man, thick-necked, broad-shouldered, with sinewy wrists and toil-distorted hands. Yet the distortion was not due to recent toil, nor were the callouses other than ancient that showed under the dirt of the one palm upturned. From time to time this hand clenched tightly and spasmodically into a fist, large, heavy-boned and wicked-looking.

The man lay in the dry grass of a tiny glade that ran down to the tree-fringed bank of the stream. On either side of the glade was a fence, of the old stake-and-rider type, though little of it was to be seen, so thickly was it overgrown by wild blackberry bushes, scrubby oaks and young madrono trees. In the rear, a gate through a low paling fence led to a snug, squat bungalow, built in the California Spanish style and seeming to have been compounded directly from the landscape of which it was so justly a part. Neat and trim and modestly sweet was the bungalow, redolent of comfort and repose, telling with quiet certitude of some one that knew, and that had sought and found. Continue reading ““The Hobo and the Fairy” — Jack London”

“Abu Al-Anbas’ Donkey” – Eliot Weinberger

“—you see you were always lost” (Thomas Bernhard)

“You just arrive in a place,” said the painter,“ and then you leave it again, and yet everything, every single object you take in, is the sum of its prehistory. The older you become, the less you think about the connections you’ve already established. Table, cow, sky, stream, stone, tree, they’ve all been studied. Now they just get handled. Objects, the harmonic range of invention, completely unappreciated, no more truck with variation, deepening, gradation. You just try to work out the big connections. Suddenly you look into the macro-structure of the world, and you discover it: a vast ornament of space, nothing else. Humble backgrounds, vast replications—you see you were always lost. As you get older, thinking becomes a tormenting reference mechanism. No merit to it. I say ‘tree,’ and I see huge forests. I say ‘river,’ and I see every river. I say ‘house,’ and I see cities with their seas of roofs. I say ‘snow,’ and I see oceans of it. A thought sets off the whole thing. Where it takes art is to think small as well as big, to be present on every scale …”

From Thomas Bernhard’s novel Frost.