I’ve often wished that someone would rewrite the end of Huckleberry Finn, delivering it from the farcical closing scenes which Twain, probably embarrassed by the lyrical sweep of the nearly completed book, decided were necessary if the work were to be appreciated by American readers. It’s the great American novel, damaged beyond repair by its author’s senseless sabotage. I’d be interested to have your opinion, or do you feel that the book isn’t worth having an opinion about, since a botched masterpiece isn’t a masterpiece at all? Yet to counterfeit the style successfully, so that the break would be seamless and the prose following it a convincing continuation of what came before—that seems an impossible task. So I shan’t try it, myself.

Tag: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Three Books

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain. Mass market paperback by Bantam, 10th ed., 1986. No designer credited, but the cover illustration is a 1981 painting by Doug Johnson, and it is the sole reason that I’ve held onto this copy for over a decade now, since I first used it as part of a class set for an eleventh grade English class I used to teach. Perhaps from a technical standpoint, I stole this book.

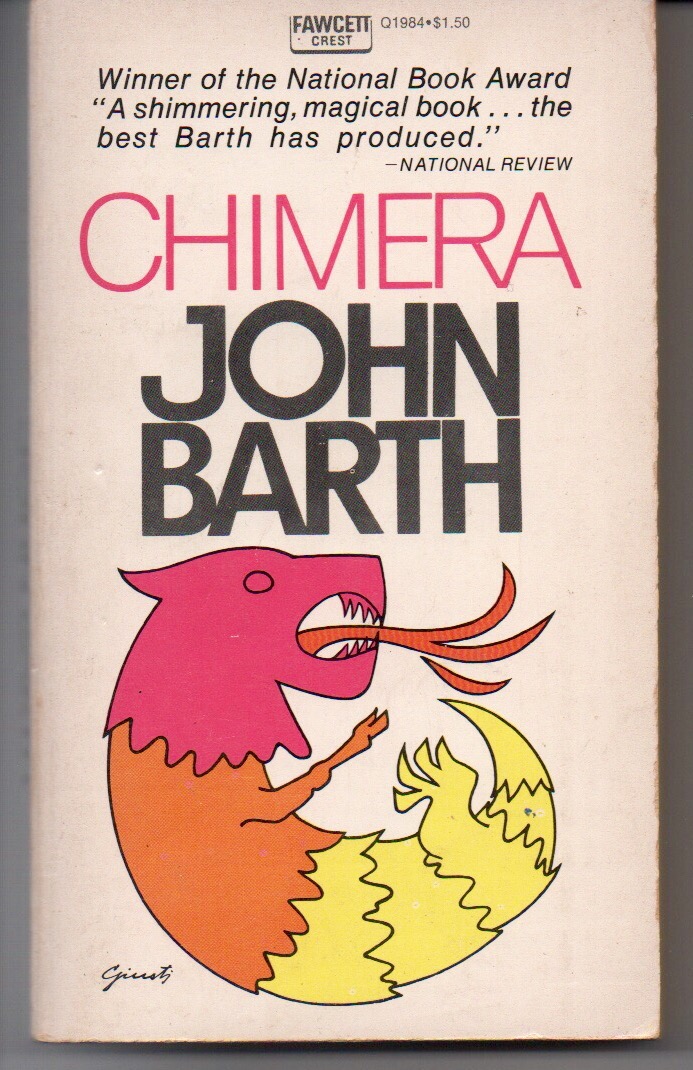

Chimera by John Barth. Mass market paperback by Fawcett Crest, 1973. No designer credited, and the cover artist isn’t named in the colophon or on the back–but the cover is signed. Perhaps the original hardback, which shares this illustration, credited the artist. I read this book in the right place and at the right time—I was a junior or senior in college, obsessed with postmodernism as a technique (rather than postmodernism as a description), and Chimera’s intense gamesmanship enchanted me. I’m pretty sure I read it after Lost in the Funhouse, and that after Wallace’s Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way. I bought this copy eight or nine years ago (having read it first as a library book), and attempted a reread and was…less impressed. Still, it would be hard for me to overstate how much Chimera did for me—how much it showcased the possibilities of literature and storytelling.

The Ballad of the Sad Cafe and Other Stories by Carson McCullers. Mass market paperback edition by Bantam. No designer or cover artist credited—which is too bad because I love the image. The most recent date on the colophon is 1971 but I am pretty sure the book was published in 1996. I bought it in 1997. It was assigned reading for a creative writing class, and that—along with Johnson’s Jesus’ Son—were the only good things to come out of that misery. (My instructor would not shut the fuck up about “craft,” and he singled out the simile I was most proud of in one of my stories as “a bit much”).

Today’s Three Books’ mass market paperbacks are part of a small cadre of a once-large selection, winnowed away over the years, usually given away to students, etc. (I have an extra copy of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in my car, should you need one).

“Twain Is the Day, Melville the Night” — Roberto Bolaño on U.S. Writers

The following excerpt comes from Raul Schenardi’s 2003 interview with Roberto Bolaño, conducted at the Turin Book Fair just months before the author’s death. The interview is written in Italian (although I’m not sure if it was conducted in Italian). The translation work is the result of two programs (Google Translate and Babel Fish) and a few dictionaries; I also used this Spanish translation as a second source for comparison.

. . . in all Latin American writers is an influence that comes from two main lines of the American novel, Melville and Twain. [The Savage] Detectives no doubt owes much to Mark Twain. Belano and Lima are a transposition of Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer. It’s a novel that follows the constant movement of the Mississippi. . . . I also read a lot of Melville, which fascinates me. Indeed, I flirt with the belief that I have a greater debt to Melville than Twain, but unfortunately I owe more to Mark Twain. Melville is an apocalyptic author. Twain is the day, Melville the night — and always much more impressive at night. In regard to modern American literature, I know it poorly. I know just up to the generation previous to Bellow. I have read enough of Updike, but do not know why; surely it was a masochistic act, as each page Updike brings me to the edge of hysteria. Mailer I like better than Updike, but I think as a writer, a prose writer, Updike is more solid. The last American writers I’ve read thoroughly and I know well are those of the “Lost Generation,” Hemingway, Faulkner, Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolff.

“A Nation of Cowards” — Ta-Nehisi Coates on the New Mark Twain Edit

At The Atlantic, Ta-Nehisi Coates weighs in on the new edit of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn that replaces the word “nigger” with “slave”–

I’m obviously not Mark Twain, but having written a book, I can only imagine how hard Twain worked. I would be incensed if someone went through my book and took out all the “niggers” or “bitches” or “motherfuckers.” It’s really just a hair short of some stranger, in their preening ignorance, putting their hands on your kid.

[. . .] the invocation of nigger by Twain is not a moral failing. But because of our needs, Twain isn’t good enough. Because we can’t handle the story of who we were, and evidently who we are, Twain must be summoned up from the dead and, all against himself, submitted before the edits of amateurs.This is our system of fast-food education laid bare: Children are roaming the halls singing “Sexy Bitch,” while their neo-Confederate parents are plotting to chop the penis off Michelangelo’s David, and clamoring for Gatsby and Daisy to be reunited.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn: One of Our Favorite Challenged Books

- E.W. Kemble’s frontispiece to the original illustrated edition

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, undoubtedly one of the Great American Novels, ranks a healthy #5 on the ALA’s list the 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books. Young Huck’s casual colloquial use of the word “nigger” and the cruel hijinks Huck and Tom play on Jim at the novel’s end are two reasons that many have sought to suppress Twain’s masterpiece, including educator and critic John Wallace, who famously called it “the most grotesque example of racist trash ever given our children to read.” Wallace went so far as to suggest that “Any teacher caught trying to use that piece of trash with our children should be fired on the spot, for he or she is either racist, insensitive, naive, incompetent or all of the above.”

I guess I should’ve been fired on the spot, as I’ve used Huck Finn in my classroom a number of times, almost always in conjunction with excerpts from Olaudah Equiano’s Interesting Narrative, some Philis Wheatley poems, and a UN report on modern human trafficking. Context is everything.

While I can concede readily that Huck, the voice of the novel, says some pretty degrading things about Jim, often meant (on Twain’s part) to create humor for the reader, to expect Twain’s treatment of race to be what we in the 21st century want it to be is to not treat the material with any justice. And while Huck Finn may be insensitive at times, it handles the issues of race, slavery, class, and escape from the dominant social order with the complexity and thought that such weighty issues deserve. Ultimately, the novel performs a critique on the hypocrisy of a “Christian,” “democratic” society that thought it was okay to buy and sell people. This critique shows up right in the second page. Consider these lines (boldface mine):

The widow rung a bell for supper, and you had to come to time. When you got to the table you couldn’t go right to eating, but you had to wait for the widow to tuck down her head and grumble a little over the victuals, though there warn’t really anything the matter with them,—that is, nothing only everything was cooked by itself. In a barrel of odds and ends it is different; things get mixed up, and the juice kind of swaps around, and the things go better.

After supper she got out her book and learned me about Moses and the Bulrushers, and I was in a sweat to find out all about him; but by and by she let it out that Moses had been dead a considerable long time; so then I didn’t care no more about him, because I don’t take no stock in dead people.

Huck’s dream is of a delicious mix, a swapping of juices — integration. Additionally, his disregard for the dead Bible heroes reveals that the white Christian society’s obsession with the ancient past comes at the expense of contemporary value. Huck, an orphan, and Jim, separated from his family, will symbolically echo Moses in the bulrushes as they use the great Mississippi as a conduit for escape, for freedom. Huck (or Twain, really) here points out that it’s not enough to look at dead words on a page, on old dead lawgivers–we have to pay attention to the evils and wrongs and hypocrisies that live today.

Twain even tells us how to read his book from the outset:

Now, it’s impossible to read a book–a good book–without finding its plot, searching for its moral, or caring about its characters, and Twain knows this. His “Notice” is tantamount to saying “don’t think about an elephant”–he uses irony to tell us we must find motive, moral, and plot here, and that we must do so through this lens of irony.

But of course, you have to read closely for all these things. I suppose it’s technically easier to call something trash, throw it in the garbage, and not have to devote time and energy to thinking about it. Who knows? You might learn something–and we wouldn’t want that, would we?

[Editorial note: Biblioklept originally published this piece in September of 2008].