Harold Bloom’s esteem for Blood Meridian may have done much to advance the novel’s reputation over the past decade. His essay on the book, first published in his 2000 collection How to Read and Why and later included as the preface to Random House’s Modern Library editions, makes a strong case for Blood Meridian’s canonical status. Bloom begins, in typical Bloomian fashion–the anxiety of influence is always at work–by situating McCarthy’s book against other heavies–

Blood Meridian (1985) seems to me the authentic American apocalyptic novel, more relevant even in 2000 than it was fifteen years ago. The fulfilled renown of Moby-Dick and of As I Lay Dying is augmented by Blood Meridian, since Cormac McCarthy is the worthy disciple both of Melville and of Faulkner. I venture that no other living American novelist, not even Pynchon, has given us a book as strong and memorable as Blood Meridian . . .

Bloom goes on to rate Blood Meridian over DeLillo’s Underworld, several books by Philip Roth, and even McCarthy’s own All the Pretty Horses. Indeed, Bloom proclaims Blood Meridian “the ultimate Western, not to be surpassed.” This doesn’t mean that Bloom is at home with the book’s violence; he confesses that it took him two attempts to read through its “overwhelming carnage.” Still, he makes a case for reading it in spite of its gore–

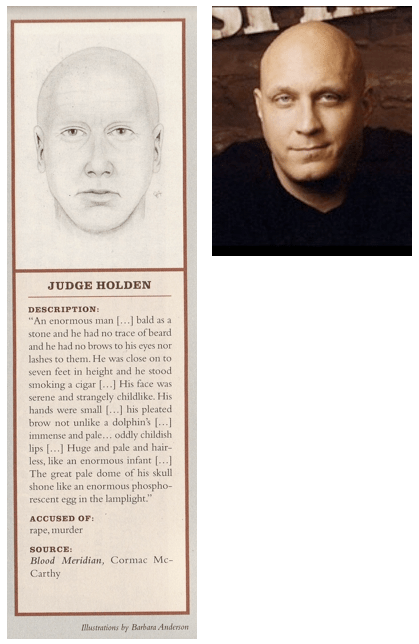

Nevertheless, I urge the reader to persevere, because Blood Meridian is a canonical imaginative achievement, both an American and a universal tragedy of blood. Judge Holden is a villain worthy of Shakespeare, Iago-like and demoniac, a theoretician of war everlasting. And the book’s magnificence–its language, landscape, persons, conceptions–at last transcends the violence, and converts goriness into terrifying art, an art comparable to Melville’s and to Faulkner’s.

Bloom repeatedly invokes Melville and Faulkner in his essay, arguing that Blood Meridian’s “high style” is one of its key strengths (unlike fellow aesthetic critic James Wood, who seems to think that McCarthy is a windbag). The trajectory of Bloom’s essay follows Melville and Shakespeare, finding in Judge Holden both a white whale (and not so much an Ahab) and an Iago. He writes–

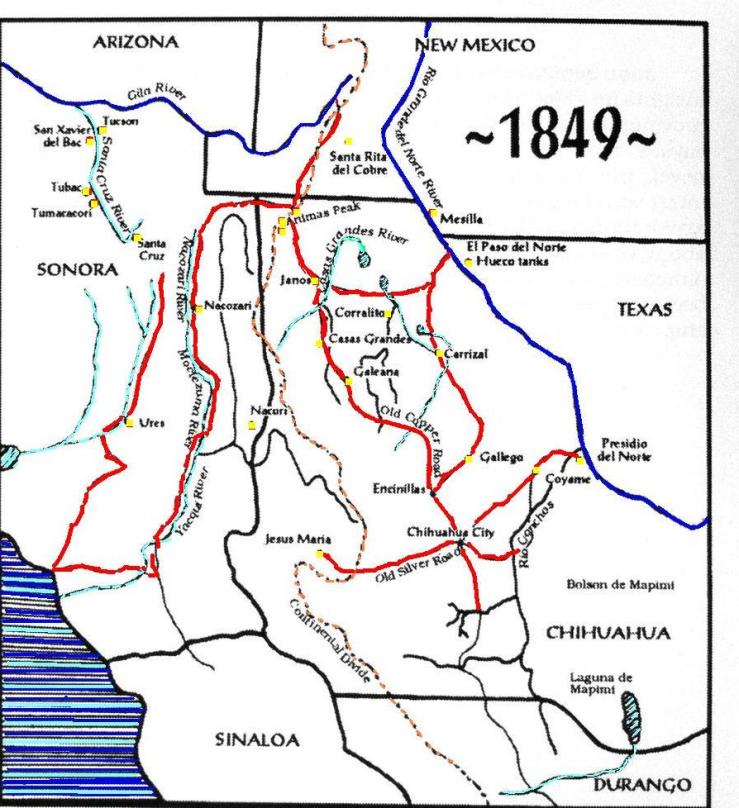

Since Blood Meridian, like the much longer Moby-Dick, is more prose epic than novel, the Glanton foray can seem a post-Homeric quest, where the various heroes (or thugs) have a disguised god among them, which appears to be the Judge’s Herculean role. The Glanton gang passes into a sinister aesthetic glory at the close of chapter 13, when they progress from murdering and scalping Indians to butchering the Mexicans who have hired them.

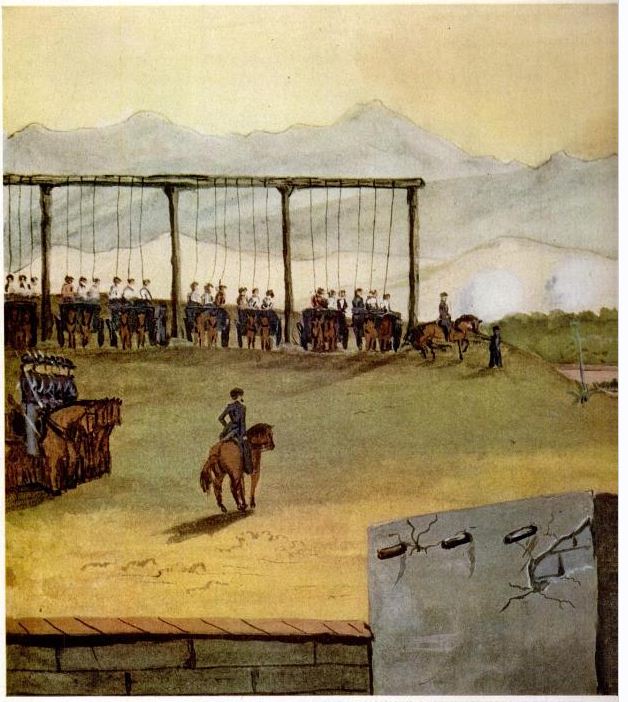

I think that Bloom’s great insight here is to read the book as a prose epic as opposed to a linear novel; to see that Blood Meridian foregrounds a deeply tragic and ironic reworking of the great American myth of Manifest Destiny. While hardly a pastiche, the book is somehow a collage; a massive, deafening collage that numbs, stuns, and overwhelms with its layers of thick, bloody prose. The effect is akin to the apocalyptic paintings of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel. Dense and full of allusion, paintings like The Triumph of Death and The Garden of Earthly Delights surge over the senses, destabilizing narrative logic. Like Blood Meridian, these paintings employ a graphic grammar that disorients and then reorients. They are apocalyptic in all senses of the word: both revelatory and portentously conclusive. And like Blood Meridian, they showcase “a sinister aesthetic glory” (to use Bloom’s term), a terrible, awful, awesome ugliness that haunts us with repulsive beauty.

In his

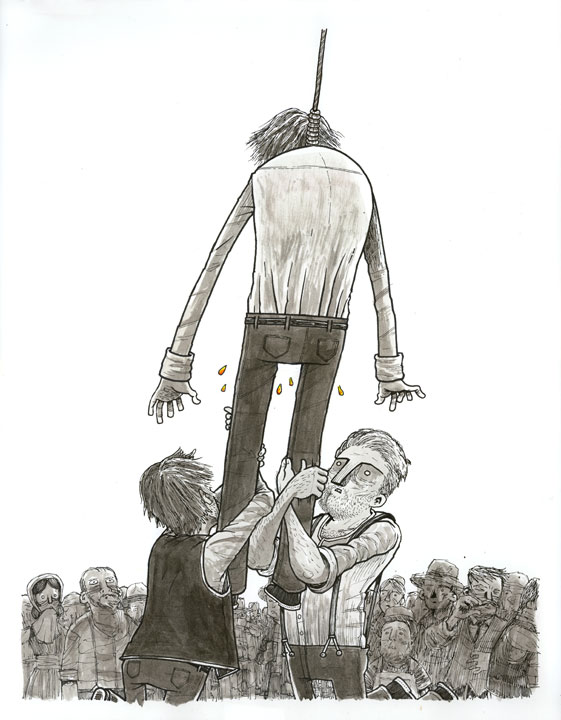

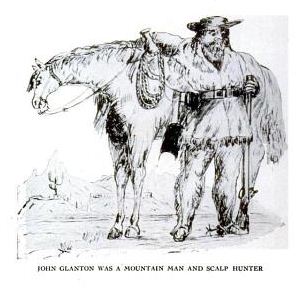

In his  According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

According to Chamberlain, John Glanton was born in South Carolina and migrated to Stephen Austin’s settlement in Texas. There he fell in love with an orphan girl and was prepared to marry her. One day while he was gone, Lipan warriors raided the area scalping the elderly and the children and kidnapping the women- including Glanton’s fiancee. Glanton and the other settlers pursued and slaughtered the natives, but during the battle the women were tomahawked and scalped. Legend has it, Glanton began a series of retaliatory raids which always yielded “fresh scalps.” When Texas fought for its independence from Mexico, Glanton fought with Col. Fannin, and was one of the few to escape the slaughter of that regiment at the hands of the Mexican Gen. Urrea- the man who would eventually employ Glanton as a scalp hunter. During the Range Wars, Glanton took no side but simply assassinated individuals who had crossed him. He was banished, to no avail, by Gen. Sam Houston and fought as a “free Ranger” in the war against Mexico. Following the war he took up the Urrea’s offer of $50 per Apache scalp (with a bonus of $1000 for the scalp of the Chief Santana). Local rumor had it that Glanton always “raised the hair” of the Indians he killed and that he had a “mule load of these barbarous trophies, smoke-dried” in his hut even before he turned professional.

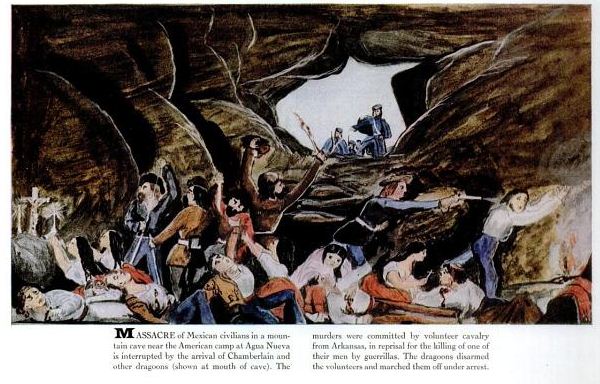

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

It’s fascinating to note how much of the Judge is already there–the pedophilia, the marksmanship, the scholarship, and, most interesting of all, the lack of hair. Confession goes on to detail the killing, scalping, raping, and raiding spree that comprises the center of Blood Meridian. Chamberlain even describes the final battle with the Yumas, an event that signals the dissolution of the Glanton gang in McCarthy’s novel.

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book

Content aside, Chamberlain’s prose also seems to presage McCarthy’s prose. In his book  You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s

You can view many of Chamberlain’s paintings and read an edit of his Confession in three editions of Life magazine from 1956, digitally preserved thanks to Google Books–here’s

Biblioklept wants to give you a copy of

Biblioklept wants to give you a copy of